This is the third installment of our climate impact deep dive. Read Part 1 and Part 2.

As governments around the world wrestle with how to stop the harmful effects of climate change, they’re finding space a useful vantage point from which to understand the scope of the problem.

The space community has a long history of supplying valuable information on the state of planet Earth. In the 60+ years since NASA deployed its first Earth observation satellites, governments have been collecting images, spectrometry, and other data to document the state of the planet and how it’s changing.

Spaceflight operations can certainly be harmful to Earth’s environment, from the soot and alumina emitted by rocket launches to the myriad metals released into the mesosphere when spacecraft burn up upon reentry. Right now, space launch and reentry is occurring at low enough levels that the environmental impact is negligible compared to other large polluting industries including aviation, but as the rate of spaceflight increases, the space industry will have to keep a close eye on its climate effects.

At the same time that launch operations are hurting the environment, the satellites they carry are providing invaluable eyes in the sky to measure emissions, track and stop environmental disasters, and provide data that allows officials to set benchmarks and goals for climate change mitigation initiatives.

The big picture

The planet is facing a warming crisis, and the world’s governments are committed to slowing it down. In 2015, 196 governments signed on to the UN’s Paris Agreement, a binding set of goals to lower greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions and intercept the harmful effects of climate change. The goals:

- Limit the global average temperature increase to <2°C above pre-industrial levels

- Ensure the peak of GHG emissions occurs by 2025

- Lower global emissions by 43% by 2030

At this year’s COP28, the UN’s yearly climate conference, the signatories of the Paris Agreement discussed their progress toward mitigating global warming. The verdict, essentially, was that not enough is being done, and the UN for the first time recommended a transition away from fossil fuels (though it did not suggest abandoning them completely).

Starting in 2024, all states party to the agreement will be required to submit a yearly enhanced transparency framework (ETF), which will require nations to more accurately measure and report their GHG emissions, and track their progress toward decreasing emissions over the levels identified as part of the agreement.

“A lot of times, these inventories are performed using calculations and estimates,” Jean-Francois Gauthier, director of business development at GHGSat, a company providing methane and CO2 emissions monitoring from space, told Payload. “So the more real data you have, the less of those estimates and calculations you’re relying upon and the more accurate your estimates become.”

Emissions monitoring from space makes the complex task of accurately quantifying the level of GHGs emitted each year much simpler and dramatically more accurate. (And the cynic in us would point out that for those countries who might be tempted not to accurately report their emissions when they miss their targets, it makes hiding those numbers from the rest of the world a lot more difficult.)

Climate research

The first step toward fixing any problem is understanding what you’re dealing with. Climate change is no different. To set benchmarks for mitigating emissions and sea level rise, for example, governments need to know where we stand today.

Space technology can help determine those benchmarks with the greatest possible accuracy and the most frequent updates. As the globe wrestles with its climate impact and takes steps to slow it down, the data it’s using comes, increasingly, from far above the surface of the Earth.

Change detection: The Earth’s environment is constantly moving and changing. Climate change researchers endeavor to look beyond the day-to-day shifts in weather patterns and fluctuations in sea levels and ice to understand the big picture of how the Earth is changing over long periods of time.

Frequent revisit is key for getting a good idea of how Earth’s environment is changing over time, and satellite observations are the best method available today for gathering the same observations over the same area over and over again for decades.

“A really significant thing for…the climate problem in particular is having continuity of observations,” said Daniel Barrie, a program manager in NOAA’s climate program office. “It’s very important to be able to characterize change at specific places in a consistent way over a very long period of time. And that can be a real challenge.”

Historically, much of this research has been done via field studies, deploying teams of scientists into a specific region to collect data. And it’s true that much of the data needed to understand the state of Earth’s environment must be gathered in person; for example, animal and plant populations in specific regions are still determined through in-person sampling.

Fueling research: While field studies have their benefits, there are some things that require a higher vantage point to see the big picture.

With satellites, “you can deploy anywhere in the world very rapidly with no deployment costs,” Gauthier said. “You don’t need to send people on the ground. You don’t need to have any sort of planning for safety or security.”

That kind of data access makes understanding developments at a large scale simpler. It also helps to identify key areas that might need that on-the-ground study. NOAA and NASA use satellite observations as one tool in a suite of many to figure out when and where field studies are needed to understand what’s going on with Earth’s environments.

- NOAA also operates its own satellites, including the GOES (Geostationary Operational Environmental Satellites) program, which can track wide regions and measure emissions. The agency makes that data available to researchers and will work with them to ensure that it’s usable.

Action items

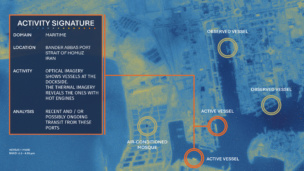

It’s not just researchers and scientists interested in using satellite data to make their climate research simpler. Many companies and organizations collecting emissions data from space are also working directly with energy companies and response teams on the ground to stop harmful actions—whether that means pollution or misuse of the environment—where they begin.

Cash for data: Methane emissions tracking is useful beyond environmental concerns. GHGSat saw a business case for pursuing the capability at its outset. As governments try to reach global climate goals, they’re incentivizing shifts towards less polluting approaches in many industries, including power and manufacturing.

Enter the carbon credit system, which several US states have implemented to try to limit emissions. Companies are able to purchase credits that act as permission slips to emit a certain amount of GHGs. If they don’t use their credits, they can sell them to other companies. In a perfect world, it’s a win-win, keeping emissions low and creating new business opportunities at once.

The system is flawed, though. There isn’t a universally accepted, reliable method of measuring emissions, making it impossible to know whether companies were telling the truth about their emissions (either by purposefully obfuscating or due to a genuine lack of information).

“If carbon is going to be traded, you need to measure it, because otherwise you don’t know what you’re paying for,” Gauthier said. “It leads to all sorts of uncertainty and therefore lack of trust in what you’re doing.”

More reliable methane emissions monitoring in space, like what GHGSat and government initiatives like NOAA’s GOES program are aiming to produce, takes some of the uncertainty out of the carbon credit system, increasing its efficacy.

Plugging the leaks: Methane and other GHG emissions monitoring can do more than mark more accurate single-source emissions data—it can also be used in action to stop pipeline leaks.

When a pipeline springs a leak, frequent observations can spot it fairly quickly. GHGSat, for example, will work with local organizations to alert them of the leak so it can be addressed in a timely manner.

“If we notice an emission, we provide an alert and then they can know right away, and if there is something they can go corroborate it on the ground,” Gauthier said. “A lot of times they can take action and fix things right away.”

- In the first 6 months of 2023, GHGSat reported that it effectively mitigated two MTCO2e of methane.

- MTCO2e = “metric tons of CO2 equivalent,” which measures the atmospheric impact of emissions in relation to CO2.

Coming up

The space industry is taking strides toward broader, higher-resolution, and more frequent measurements of the Earth’s surface to track and mitigate the harmful impacts of climate change.

NASA recently launched its TEMPO (Tropospheric Emissions: Monitoring of Pollution) instrument, a space-based spectrometer that will perform air pollution monitoring across North America. NOAA is working towards deployment of its GeoXO (Geostationary Extended Observations) program, which will use newer technology to improve upon the US government’s current weather tracking and atmospheric monitoring. And the commercial EO sector is constantly evolving, incorporating more hyperspectral capabilities that can reveal details about land management and reveal climate impacts on the ground.

Progress is coming, too, on the policy side, with agencies coming around to the potential of space-based observations to improve their understanding of climate change and its impact. The Biden administration recently announced a GHG emissions monitoring strategy that NOAA, NASA, the EPA, and NIST will collaborate on to improve the nation’s emissions data.

As the looming threat of permanent, irreversible climate change becomes ever more present, the use of space observational data will be essential for understanding, preparing for, and addressing the challenges of a different world.