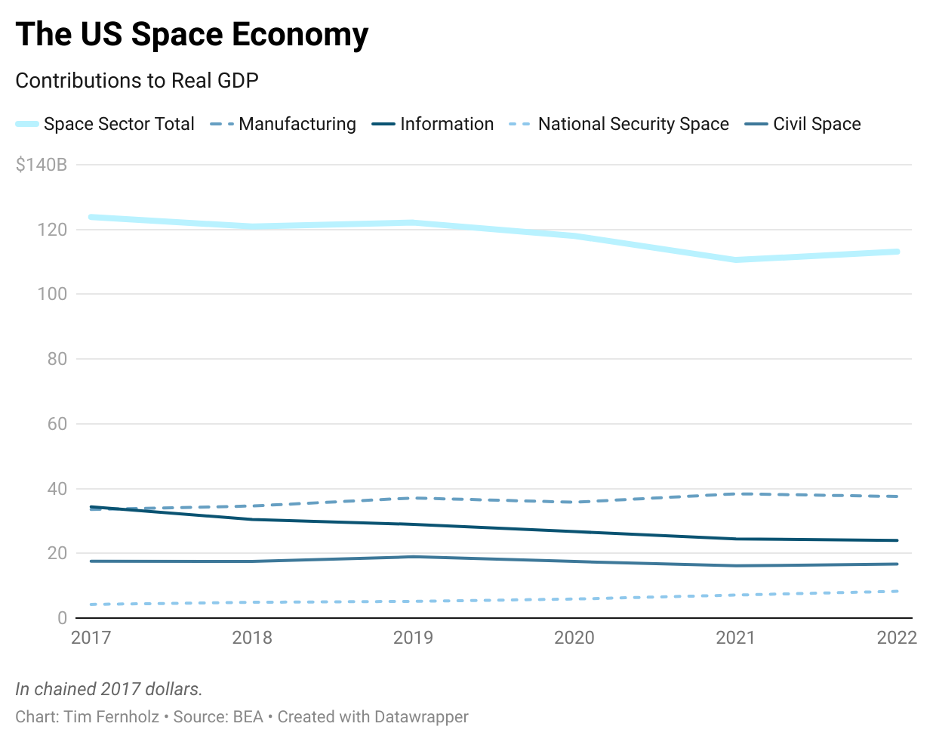

The space sector contributed $131B to American GDP in 2022, according to the most recent and precise analysis by the US government’s Bureau of Economic Analysis.

“The takeaway is that growth in 2022 in real GDP was faster in the space economy than the overall economy, and that’s one of the first times that’s happened,” BEA economist Tina Highfill, who leads the space initiative, told Payload. “This was largely due to national defense spending, US Space Force, and particularly R&D.”

Indeed, national security space spending has nearly doubled since 2017.

Why it matters: Measures of the space economy by the private sector tend to suffer from double-counting or depend on how you value a private company. The statistical agency, by contrast, relies on tax filings, private information, and other government data. It launched a program in 2019 to precisely measure the space economy, adding more detail with each successive release.

One thing that may surprise readers: In real terms, the US space economy has shrunk by more than $10B since 2017. That reflects some negative trends, such as inflation and the steady decline of satellite TV subscriptions, once the biggest earner in the space biz. But it also confirms something we’ve long suspected: Innovation is driving down the cost of space hardware.

“We see manufacturing prices actually declining for most of the period,” Highfill, who co-authored a paper outlining those findings in detail, said. “That’s related to satellite manufacturing, ground equipment—it’s getting cheaper to buy those things, which really stands out.”

Filling the gaps. Some of the info is surprising:

- The $2M attributed to legal services for space in 2022. Anybody paying attorneys to solve their compliance problems knows that’s an undercount, but Highfill noted that most law firms don’t break out their space services when reporting revenue.

- The $7M in value added to the space sector by the wood products industry—most likely because a company that primarily works in that space made something else for the space industry, Highfill says.

What’s next: After several years as an experimental project, Congress has permanently funded the effort to measure the space economy, a signal that policymakers find the work valuable. Now, Highfill’s team will attempt to make the estimates more timely, moving from eighteen months of delay to twelve, in addition to pursuing state-level estimates.

And Europe shouldn’t feel left out: ESA and Eurostat are looking at the BEA’s project with an eye toward creating their own comparable dataset.

“This is a big deal,” Highfill said, “an endorsement of what we’ve done, and also the first time we can really compare the US space economy with another country’s space economy and know we are comparing the same thing.