We know less about the vast, mysterious universe we live in than we can even begin to comprehend. For thousands of years, astronomers have looked out to the heavens to try to make sense of it all, and bit by bit, we’ve increased our understanding of how it all works.

Now, researchers may have made a dent in understanding one of the universe’s most ubiquitous and least understood forces: dark energy.

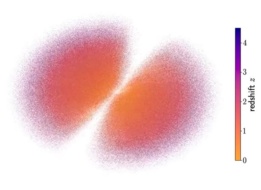

The study, published yesterday in The Astrophysical Journal Letters by researchers at the University of Hawai’i, STFC RAL Space, and Imperial College London, includes the first empirical evidence of “cosmological coupling,” a theory first predicted in Einstein’s theory of general relativity. It suggests black holes increase in mass more quickly than they accrete outside mass, and that the expansion of black holes is “coupled”—i.e. proportionate—to the universe’s expansion.

Dark energy as a “vacuum force” produced by the black hole could explain that bonus increase in mass.

The universe we live in

For a long time, the prevailing theory explained that the Big Bang exerted an incredible force that caused the universe to expand outwards. Eventually, the gravitational forces from all the mass in the universe were expected to slow down that expansion.

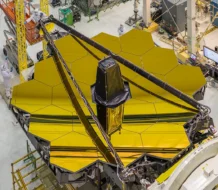

“That’s the universe we thought we lived in until the late 1990s,” Dr. Chris Pearson, a coauthor on the paper and researcher at STFC RAL Space, said in a video about the research findings. In 1998, Hubble observations revealed that the universe is indeed expanding, but at a faster rate than in the past. Some unknown force was actually pushing cosmological objects apart.

The dark energy problem

The idea of dark energy emerged as a response to this finding. “Dark energy pervades the whole of space, and kind of acts like negative pressure,” Pearson said. “So dark energy is actually pushing things apart rather than keeping them together.”

Scientists believe that only about 5% of the universe is made up of the regular bits of stuff we’re used to (i.e. atoms). Nearly 70%, on the other hand, is dark energy.

Finding the source: The researchers set out to study the evolution of black holes over time. They turned their focus on distant giant elliptical galaxies that have stopped forming stars, as the supermassive black holes at the center of these galaxies have access to comparatively little matter for absorption.

Distant supermassive black holes, the researchers found, increased in mass more quickly than could be explained by astrophysical processes like accretion. To explain this, the researchers introduced the idea that dark energy exists within the black holes, and found that this explanation evades the concept of a singularity—a phenomenon where a black hole crushes mass into nothing, which is not possible in our current understanding of physics.

According to the paper, the amount of dark energy that would have been produced in supermassive black holes to balance the mass discrepancy is consistent with the theorized amount of dark energy in the universe.

Looking ahead: This is only the first observational evidence that could explain the mysterious origin of dark energy. Now, astronomers can use these findings as a framework to check and double-check the estimates made in this paper and experimentally verify whether black holes are a reasonable source for dark energy.