SpaceX is a major player in the launch and satcom markets. Now, its $1.8B Starshield deal to build a swarming remote-sensor constellation for the National Reconnaissance Office, which was detailed by Reuters last week, marks a potential inflection point for the EO business—and the way it does business with military and intelligence agencies.

Deja vu: SpaceX’s decision to enter the satellite communications business with Starlink up-ended that sector, forcing consolidation among legacy firms and making large, LEO constellations a reality. A move into EO could present a big challenge to companies selling space data already.

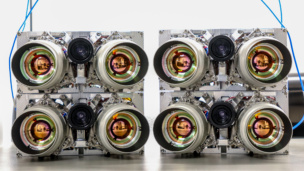

One bit of good news for incumbents is that SpaceX is reportedly buying the imaging sensors for the vehicles from another firm; its core competencies here are quickly building low-cost, autonomous spacecraft with fast data transfer, including inter-satellite laser optical communications.

Buy to own? It’s not entirely clear if the final network will be operated as a service, as SpaceX generally prefers doing business, or handed over to the NRO, as done with traditional spy satellite systems.

Some industry sources believe that the deal was a competed purchase order, which would entail the government taking ownership and operating the constellation. SpaceX did not respond to requests for comment, but that would jibe with former SpaceX advisor Gary Henry’s comments in January that the DOD wanted to buy its own Starship to operate on classified missions.

A defense source, however, suggested that the deal could be a hybrid agreement that might evolve as the US military continues to update its approach to operating satellite constellations at the Space Development Agency.

The NRO did not address a question about the contract, but shared a statement saying “we know that the NRO can best maximize our impact against today’s biggest national security challenges by developing partnerships to enable the intelligence products needed for our customers across defense, intelligence, and civil communities. To achieve this, we are deepening our relationships with other government agencies, the private sector, academia, and other nations across the full lifecycle of our space-based ISR mission.”

The commercial perspective: Payam Banazadeh, a founder, board member, and former CEO of Capella Space—a SAR data provider that works closely with the US government— told Payload that there is still opportunity for dual-use commercial companies, even if the NRO gets its own rapid revisit capabilities.

“NRO has openly discussed their strategy for developing a hybrid space architecture that integrates both government and commercially operated satellites,” Banazadeh said, but satellites owned by the government still face limitations like high levels of classification, and companies may have unique sensor IP.

“While SpaceX is capable of offering more cost-effective solutions, and quicker delivery times relative to traditional primes, it cannot completely replace the hybrid model,” he said. “Nonetheless, it is evident that the NRO continues to make significant investment in its traditional acquisition model of owning and operating its satellites relative to purchasing imagery from commercial entities.”

And if Starshield did operate as a service? “It would be extremely controversial, and pretty much guarantees a huge protest by earth observation companies if NRO buys services from SpaceX,” Banazadeh says. “That would be direct competition to EOCL and other commercial layer programs.”

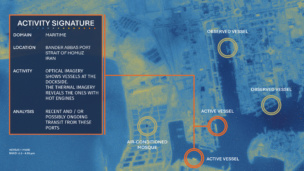

And then there’s geopolitics: There have been a dozen unacknowledged Starshield prototypes mixed in with regular launches of Starlink satellites, per Reuters, that escaped wide notice until last week. China has now taken notice, with state-affiliated social media criticizing SpaceX’s role in the project.

Of course, Chinese leadership already knows SpaceX is one of the US military’s most important space contractors. But this level of public criticism over this constellation is new, and may increase concerns about SpaceX CEO Elon Musk’s other business interests in China, notably its Tesla production plant, and his purported communications with Russian leader Vladimir Putin.

Beyond Musk’s complications, the issue of intermingled commercial and military satellites will continue to worry private companies. Russia’s invasion of Ukraine saw cyber attacks on civilian communications satellites, and the sanctioning of executives at private EO providers who work with the government.

“The most interesting question is whether Russia, China and other countries will explore exotic anti-satellite weapons to attack swarms of small satellites,” said Jeffrey Lewis, an expert in non-proliferation at the Middlebury Institute for International Studies who frequently analyzes satellite imagery. Distributed constellations are probably more resilient to attack now, he continued, but it’s only a matter of time before adversaries figure out how to threaten them.

Thus far, however, there haven’t been direct attacks on private satellites, and it’s not clear how insurance underwriters would respond to them. Brian Weeden, a space security expert at the Secure World Foundation, noted that experts debate whether it is even technically legal to intermingle civilian and military assets in space.