The ISS celebrated 25 years of continuously having humans onboard in November. But, even as the orbiting lab is celebrating new milestones, it’s also counting down the dwindling days until it is deorbited into its watery grave.

The space community has long known that the ISS agreement has a 2030 expiration date. But this year, headlines about the end of the station—and debates about America’s presence in LEO—have shifted the focus beyond 2030 to the companies building Commercial LEO Destinations (CLD) vying to be the station’s successor.

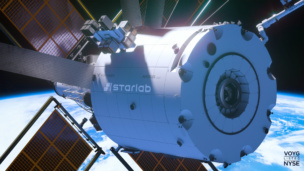

“Certainly this year, CLD started getting more attention mainly because of changes in the procurement approach that created news, as well as things that happened in the ISS world,” Marshall Smith, the CEO of Starlab Space, told Payload. “It’s reminding people that the ISS isn’t going to be up there forever.”

Rear view: The ISS—and the plans for after its demise—made headlines this year, including:

- The Trump administration’s budget proposal, which would cut the ISS budget by $508M, reduce the crew size, and cut research in the lead up to the habitat’s retirement.

- An August memo from interim NASA chief Sean Duffy, which changed the acquisition method for the CLD program to instead rely on Space Act Agreements.

- That memo also changed NASA’s previous goal of a continuous crewed presence, instead requiring the stations from CLD competitors to host four-person crews for a month at a time.

Full-time?: The latter point became a huge point of contention for the space industry, with many arguing that not requiring a continuous presence will give China a leg up—both in LEO, and in the race to the Red Planet. Beyond the geopolitics, however, Smith pointed out an economic effect: Having missions that only last a few weeks will mean many companies can’t fly their payloads or research to orbit.

“Will they go out of business? Maybe,” he said. “Do you need multiple crew and cargo vehicles for short missions? I think all of those things are things we have to think about, when we think about what kind of space station the US wants or needs.”

However, Vast CEO Max Haot argued that the shorter-term missions now required by NASA are a “stepping stone” to get to a continuous presence, and not a substitute designed to take their place.

“There’s confusion, and people saying [doing] the 30-day mission ASAP is a distraction. That can’t be further from reality,” he said. “Incremental stepping stones are part of everything, including the ISS [when it was built.]…It’s a better approach than nothing, until you’re ready.”

Company updates: We chatted with leaders from each of the main companies competing for for CLD contracts on their 2025 highlights:

- Starlab spent the year completing its design process, including completing system and subsystem level preliminary design reviews, Smith said. The company also just installed a high-fidelity mockup at JSC to install for testing. Smith said the company has sold 70% of the payload capacity on Its first mission, which is on track to launch in 2029.

- Vast completed both the design of Haven-1, and the construction of the facilities where its modules will be built, Haot told Payload. It launched a demo sat in November to test some non-crew systems in orbit, including power, communications, and videos—which are performing well, even during a recent solar storm that delivered a large dose of radiation to the hardware, Haot said.

- Axiom Space is working to launch a two-module, free-flying station by 2028—a stepping stone towards the goal of an independent four-module station, Jared Stout, the company’s chief global policy officer, told Payload. The company completed final welds on its first module in July, and also completed preliminary design review on its second module in December.

“We’ve moved from planning to execution across multiple programs, demonstrating that commercial space infrastructure isn’t just a future concept—it’s happening now,” Stout said. He also highlighted the launch of the company’s Ax-4 mission to the ISS, and the establishment of its Axiom Space University Alliance to boost microgravity research.

What’s next: If 2025 was the year that CLD competitors joined metal, sold inventory, and launched demos, 2026 is the year that all that hard work could pay off.

Next year, NASA is expected to award at least two contracts under Phase 2 of CLD—with a total value of up to $1.5B. As far as the companies are concerned, the decision can’t come fast enough.

“The ISS timeline is fixed—2030 is not negotiable. Any delay in the CLD downselect compresses the transition timeline, and increases risk to continuous US human presence in LEO,” Stout said.

Which two companies are picked will send an important signal to the investor community, which will be critical to the program’s success since CLDs are intended to have private funding and commercial applications.

“That is the most critical thing that needs to happen—they need to make those selections,” Smith said. “The difference is that NASA is asking for the private market to fund quite a bit of the activity, probably 70%. It’s vastly different than the way it was in the previous commercial programs, with crew and cargo, where [NASA] funded most of it.”

Vast is also planning to launch a single-module station, Haven-1, in May to begin offering commercial two-week missions for up to four astronauts.