If all goes according to plan, the first European rover on the Moon will be delivered and operated by a Japanese company—thanks to Tokyo-based ispace’s omnipresence in the world’s robotic race to the Moon.

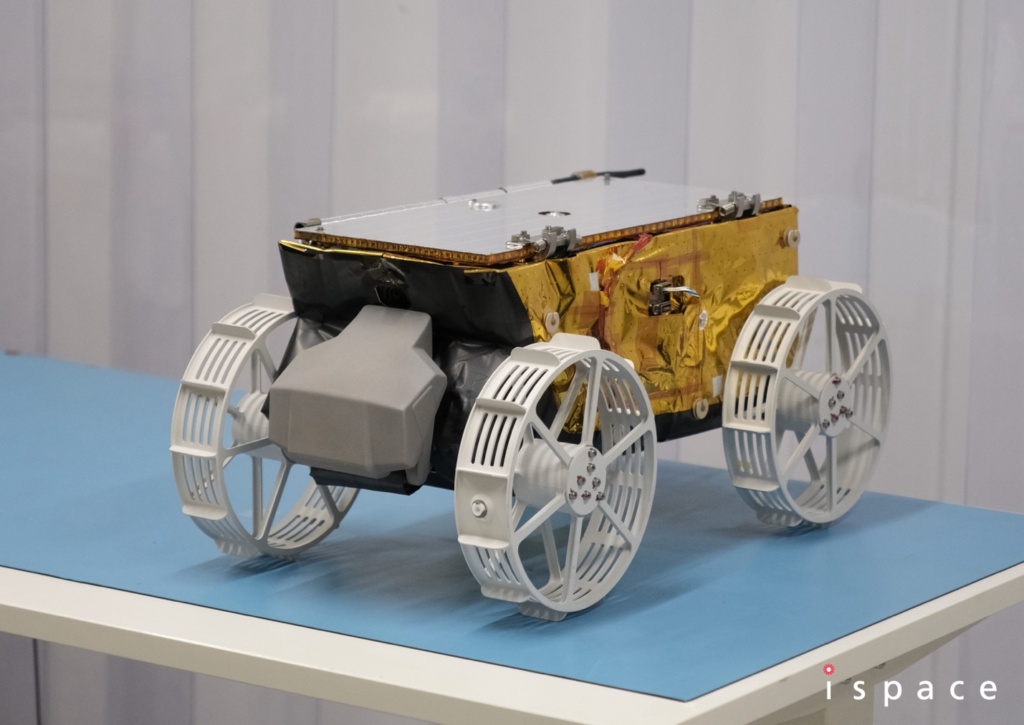

“I’m very proud that we can bring Luxembourg and Europe to the surface of the Moon for the first time,” Julien Lamamy, the CEO of ispace Europe, told reporters yesterday as he unveiled the finished 5-kg micro rover, dubbed Tenacious.

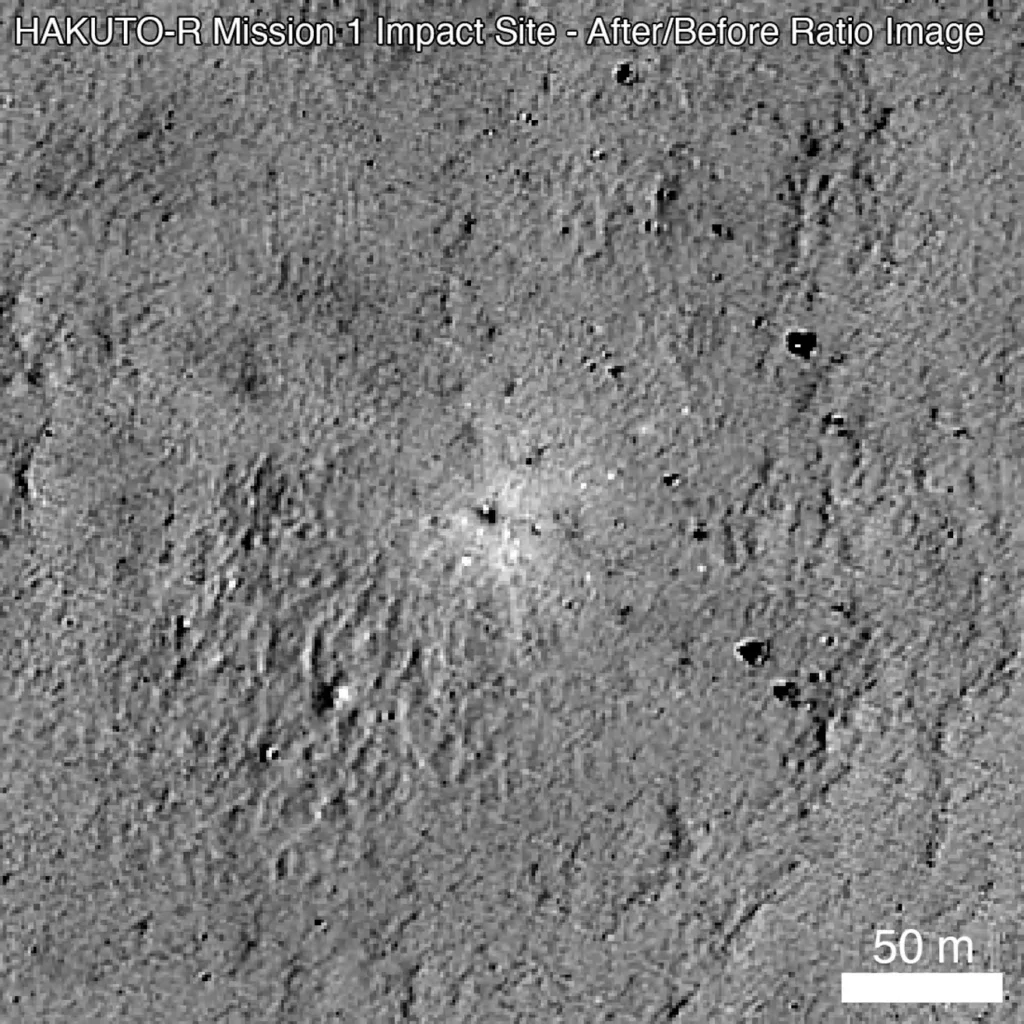

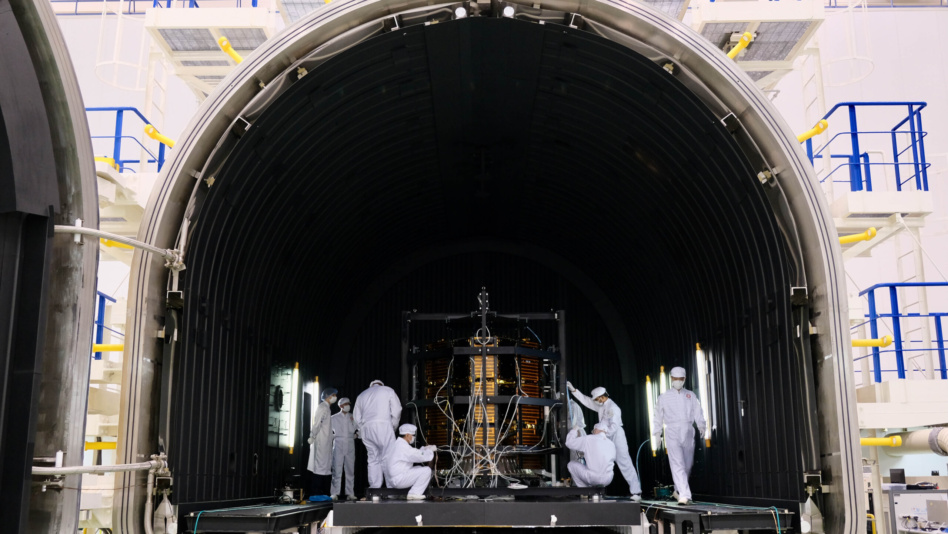

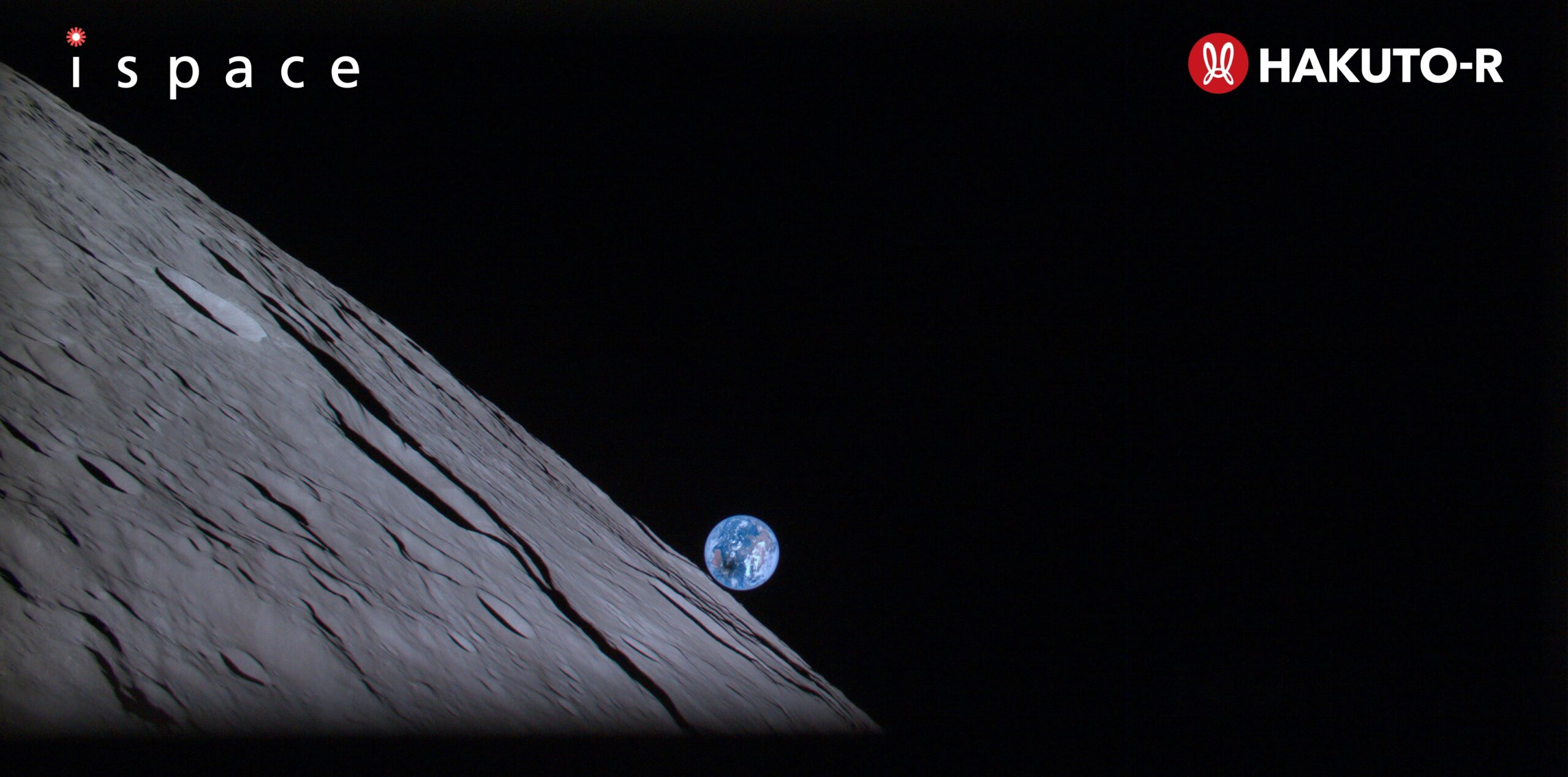

Next week, the vehicle will be shipped to Japan and integrated into ispace’s Mission 2 lander, which is expected to launch this year. ispace’s first attempt to send its Hakuto lander to the Moon in 2023 failed after its guidance software was unable to determine the distance to the surface. The spacecraft ran out of fuel before crashing into the regolith.

Undaunted, ispace—valued at $357M by investors on the Tokyo Stock Exchange—is among a handful of firms trying to shape an unproven commercial market on the Moon, building off the global interest in a lunar return and new models of private activity in space.

It’s not just the private sector with its eyes on the Moon. Japan’s government has become a major partner in the Artemis lunar return, supporting ispace in its bid to contribute to the program and as one of the first states to join the Artemis Accords legal framework for activity on the Moon.

Japan’s lunar agenda

JAXA is keeping busy, according to JAXA VP Yasuo Ishii.

- In January, its SLIM lander touched down precisely on the Moon, and despite landing at an awkward angle, survived three lunar nights.

- In April, JAXA signed a deal to provide a pressurized Moon rover that can carry astronauts and also operate autonomously. Toyota will build the vehicle—another sign of Japan’s ostensibly terrestrial companies playing a large role in space exploration—and in return, NASA will send two JAXA astronauts to the lunar surface.

- Japan is building the Lunar Polar Exploration (LUPEX) lander, a collaborative project that will launch with an ISRO rover and scientific payloads from JAXA and ESA next year.

- JAXA is contributing key components of the Lunar Gateway station and plans to send an astronaut there on a future mission, as well as resupply it with the robotic HTV-XG spacecraft.

Another crack at the Moon

Japan’s private lunar sector can be traced to 2010, when Takeshi Hakamada, wanting to compete for the Google Lunar XPrize, founded the organization that would become ispace. While five finalists, including ispace, were chosen, none made the deadline, and the prize was never awarded. The contest seeded engineering efforts around the world, including the first privately-built lander to impact the Moon, Israel’s Beresheet. Some have fed into NASA’s CLPS program, which hires private companies to deliver payloads to the lunar surface.

Ispace, which became a private firm in 2013 with Hakamada as CEO, is participating in CLPS—it will be the design agent for a team led by the US firm Draper that plans to launch 300 kg of payload to the far side of the Moon in 2026. But its first two missions were backed by private investment, sponsorships, commercial deals and JAXA grants. Company officials say it has the funding to launch five more missions.

Mission 2, expected to launch this year, is entirely commercial, according to Hakamada. He told Payload he’s confident his engineers have solved the problems that led to the first mission’s hard landing as evidenced by the mission’s name: Resilience.

The key payloads on board are intended to further the company’s vision of resource extraction on the Moon. The rover is designed to explore for resources and collect regolith, which would make ispace the first private company to fulfill a contract with NASA that would allow the space agency to purchase lunar samples. At a total price of $5,000, this is mainly an exercise in legal precedent-setting under the Artemis Accords—and under Japan’s lunar resources law, which was enacted in 2022 with ispace in mind.

Another payload is an electrolyzer developed by the Japanese HVAC firm Takasago Thermal Engineering. The experimental device will attempt to extract water from the lunar surface by heating it and then splitting the captured steam into hydrogen and oxygen gas for storage. If it’s successful, that would be another first for humanity’s space mining efforts.

Water or not, here we come

Ispace executives are vocal about their long-term vision for the lunar economy: At the rover unveiling, CRO Atsushi Saiki pointed to estimates of 6.8B tons of water on the Moon and argued that it would be more economical to refuel and service satellites from lunar platforms than Earth’s deep gravity well. Similar cases have been made for using water, hydrogen, and oxygen generated on the Moon for enabling long-term lunar and Martian exploration.

There are reasons to be skeptical, however. Scientists still don’t know precisely where the water ice, detected with remote sensors aboard several US and Indian space probes, is distributed on the lunar surface, or how dense it will be in regolith or dark craters. That’s one reason for the widespread dismay at the cancellation of NASA’s Volatiles Investigating Polar Exploration Rover (VIPER), which was designed to answer just those questions.

And then there’s the math. NASA chief economist Alexander MacDonald, a proponent of public-private partnerships, challenged the assumptions in many business models for lunar water. If the cost of getting the hardware required for water extraction, processing, and storage to the surface of the Moon is low enough for their business model to succeed, it might be low enough to simply deliver that water from Earth.

“Ironically, lunar ISRU makes more sense if the cost of getting to the Moon is more expensive. The cheaper it gets, the simpler it is to launch water from Earth, at least for the first few decades,” MacDonald said at the Spacetide conference in Tokyo this month.

How to survive fourteen years as a Moon company

“The new space industry is good for non-space people,” Masayuki Urata, ispace’s director of Indo-Pacific sales, told Payload in Tokyo. That’s true for ispace’s customers as well: The company has survived through years of tech development in part because it has revenue from areas that American competitors like Intuitive Machines and Astrobotic don’t tap into. Urata, for example, sports a Hakuto-branded Citizen Watch that sells for between $1,475 and $2,995, depending on the model.

The company’s adoption of corporate sponsors like Mitsui Sumitomo Insurance has paid off in other ways as well—the two organizations collaborated to create the first lunar insurance policy on Mission 1; wisely, in retrospect. That policy paid the company $25M in 2023, softening the blow of the spacecraft’s loss.

“The uniqueness we can bring from the commercial industry is, I think, sustainability, thanks to the diversity of customers,” Hakamada said in Tokyo this month. “We don’t rely on a single customer for a single mission…that also lowers the entry barriers for the smaller countries or the small companies, too.”

Before the launch of Mission 1, Hakamada told Payload about the challenges facing his company: “Money, of course, technology, of course, however I think the most difficult hurdle at this moment is the mindset of the people. Most regular people think, when they hear about space, it’s just a dream.”

Asked recently about that hurdle, Hakamada said that even though ispace’s first landing attempt failed, how close they came helped convince the government that his efforts are worthy of support, and gave credence to its plans for a new public fund for private space R&D.

But for the public at large, Hakamada says, ”there still is the perception that we are kind of dreaming—we are trying to prove it.” Mission 2, you’re up.