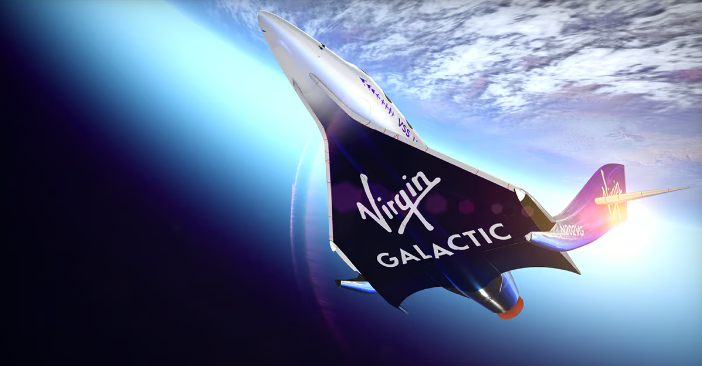

Virgin Galactic sent three Italian researchers to the edge of space last month, and is expecting to launch its first tourists as soon as Aug. 10. Three people—including businessman and race car driver John Shoffner—hitched a ride on a SpaceX Crew Dragon for an eight-day stay on the ISS in May. And Blue Origin, which has paused its commercial flights after an issue on an uncrewed mission last year, has sent Star Trek’s William Shatner past the Kármán line.

Space travel is still too expensive to be attainable for the average person. But as companies launch non-astronauts with increasing regularity, Congress is wondering if it’s time to impose some rules.

Learning is fun: The FAA is charged with making sure people and infrastructure around launch sites are protected from potential disasters. But those strapping in for a bird’s-eye view of the planet aren’t offered the same protections. Commercial human spaceflight operates under the principle of informed consent, where wannabe space tourists must sign a waiver acknowledging that what they are undertaking is risky.

The government is prohibited right now from enacting additional regulations to keep space tourists safe. Congress imposed an eight-year “learning period” in 2004, arguing that too many rules upfront could squash the nascent industry. Because space tourism has ramped up slower than predicted, that initial rulemaking moratorium has been extended twice, in 2012 and 2015.

That last extension will expire on Sept. 30, raising questions about whether lawmakers should give the industry more time to experiment without the burden of regulations or if it’s ready for some rules.

What’s next? Industry is arguing that it needs more time. Karina Drees, president of the Commercial Spaceflight Federation representing 85+ companies including Blue Origin, SpaceX, and Virgin Galactic, told Congress last week that her organization supports another multi-year extension of the learning period because the industry has grown slower than was expected when the last extension passed.

Drees also argued that imposing regulations now would actually make commercial spaceflight less safe in the long run.

“The only way to achieve [safety] in the long term is by focusing on industry-consensus standards today rather than writing regulations today based on the vehicles that are designed today,” she said at a House Science, Space and Technology Committee hearing. “There’s a lot that we have to sacrifice, potentially, and give up if we start regulating now versus allowing companies to continue iterating on their own designs.”

The spice of life: Other officials argued that it will be too difficult to regulate such a small industry, especially when the vehicles flown by the three active commercial human spaceflight companies look very unique—a big difference compared to more regulated industries, where all commercial aircraft or cargo trucks look generally the same.

“It’s a very diverse industry right now,” Caryn Schenewerk, president of CS Consulting, said at the hearing. “Writing a regulation based on a number as small as three is a challenge in and of itself, much less in an industry where you haven’t had a consolidation of design.”

SOS: Once people do start flocking to space in larger numbers, they shouldn’t expect that officials can come rescue them if something goes wrong. Some people drew comparisons between space travel and deep-sea tourism after the OceanGate submersible imploded last month on its trip to the Titanic wreckage. But, while both industries cater to the uber-rich and operate under informed consent, Josef Koller, systems director of the Aerospace Corporation’s Center for Space Policy and Strategy, told Congress that there is at least a framework in place to deal with disasters at sea.

“The Coast Guard immediately rushed to the rescue,” Koller said of the OceanGate tragedy. “We do not have anything in place for in-space rescue. We have no strategy in place, we have no capabilities, and I think we need to start now to learn from examples like the submersible.”