Voyager Technologies secured a patent from the US government covering its unique process of manufacturing crystals in microgravity to support future optical communications use cases, the company announced this week.

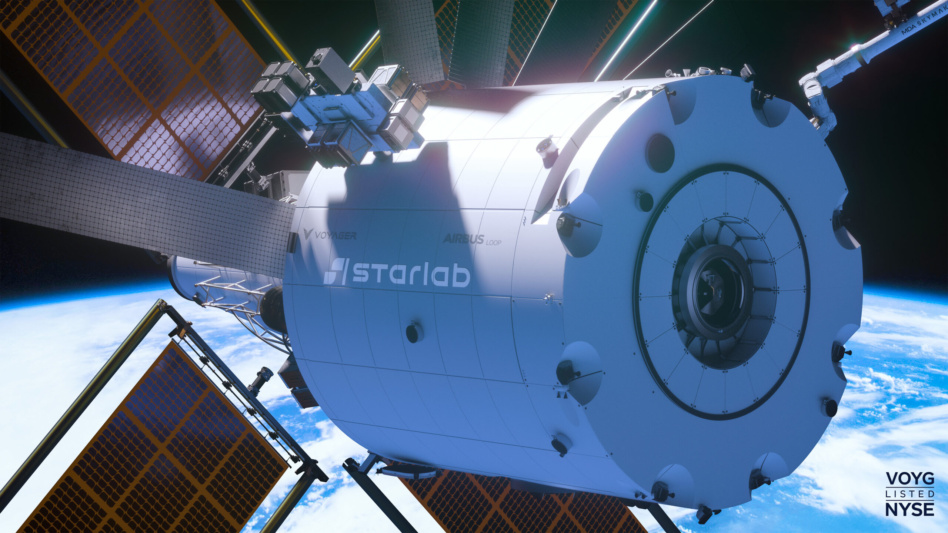

Voyager plans to send its patented process to the ISS this spring to demonstrate the hardware, but this mission is just the beginning. Voyager CTO Paul Tilghman shared with Payload the company’s long-term vision, which depends on larger in-space manufacturing hubs, such as Starlab, and reliable, high-volume reentry services.

Bigger and better: The process Voyager patented is focused on creating crystals that form the basis of optical comms and modern computing infrastructure. On Earth, these crystals are nearly impossible to build with precision, as gravity pulls down on the material during formation.

In space, microgravity allows these crystals to form with far fewer defects. That means space-made crystals are five to eight million times larger than those made terrestrially, and much more capable at handling optical comms and computing.

“We’re able to have higher signal fidelity, which ultimately means more bandwidth,” Tilghman told Payload. “It also means less losses as we try and load multiple signals onto an optical fiber.”

Because of the increased performance and precision, the process could ultimately reduce the error rates in high-bandwidth AI and cloud computing models that rely on these types of crystals.

While high-quality crystals are already in high-demand from the rapidly growing AI community, the benefits don’t just end there. Tilghman explained that if the manufacturing process on orbit takes off, other use cases will be quick to take advantage of the output.

- Terrestrial communication lines, both optical fibers and laser comms, will be able to handle more bandwidth;

- Hyperspectral remote sensing sats will be able to spot resources with greater accuracy;

- Optical computers will shrink in size.

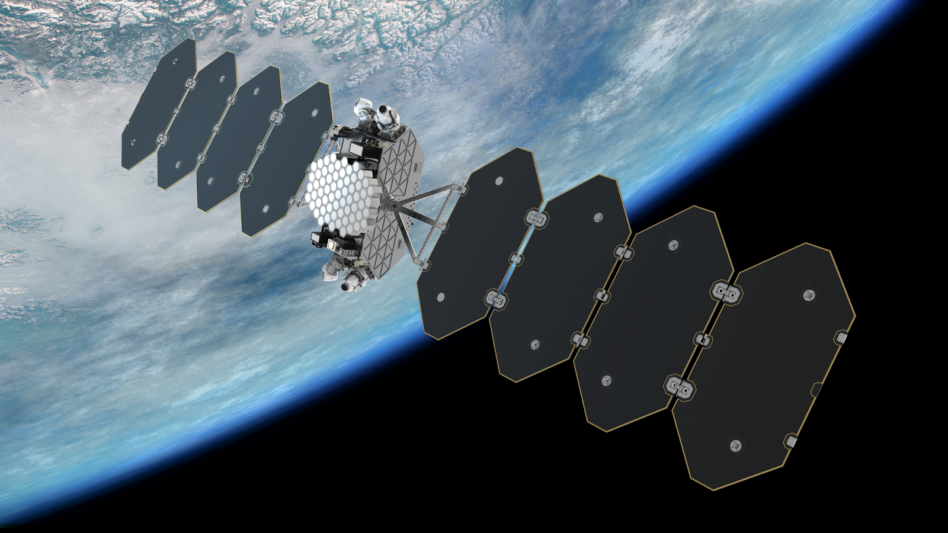

Make it happen: Voyager’s demo this year aims to bring an experimentally useful quantity of crystals back from the ISS. The ultimate goal, however, is to create a high-volume manufacturing process.

For that reality to come to fruition, the space economy needs to build out the infrastructure to support in-space manufacturing at scale. Tilghman pointed to Voyager Technologies’ planned commercial space station, Starlab, as a prime location to host the manufacturing hardware, but acknowledged that a robust complimentary industry would need to come alive to make the process economically viable.

“There’s two dimensions of scale. There’s how much crystal you can generate at once, and then there’s, how do you actually do this as a repeatable process?” Tilghman said. “In my mind, the next two primary drivers that will propel the rest of the space economy forward are manufacturing and downmass because in the immediate future, manufacturing without the ability to bring it back has fairly limited purpose.”