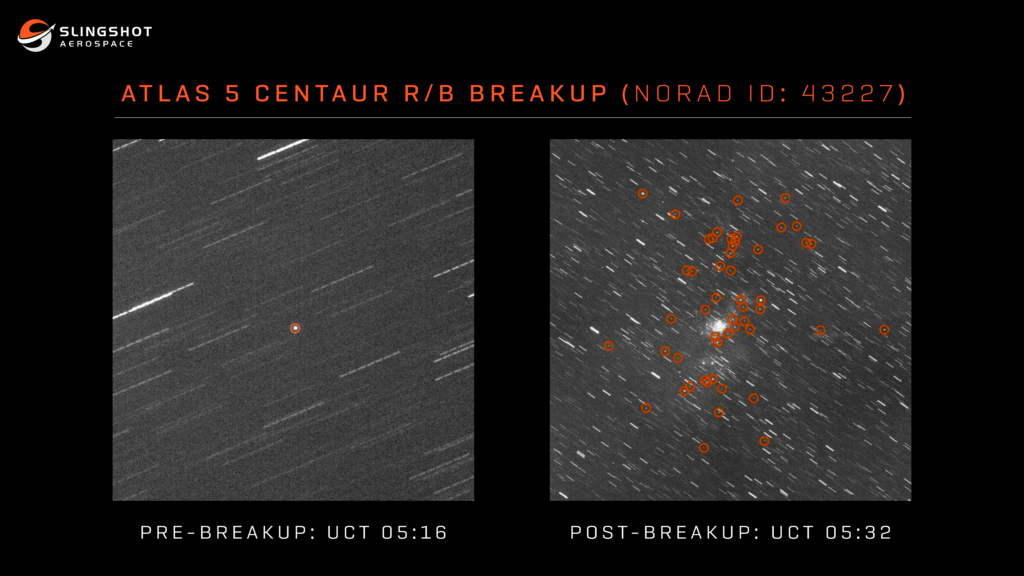

The second stage of a ULA rocket that sent a NOAA weather satellite to orbit in 2018 broke apart dramatically in orbit last week, generating a debris cloud first tracked by Slingshot Aerospace.

Slingshot publicized the debris-generating incident more than a day before the US DoD updated its public database of space objects.

“That just demonstrates the value of commercial space domain awareness capabilities for being able to do things that even the government, right now, is not able to do,” said Audrey Schaffer, Slingshot’s VP of Strategy and Policy.

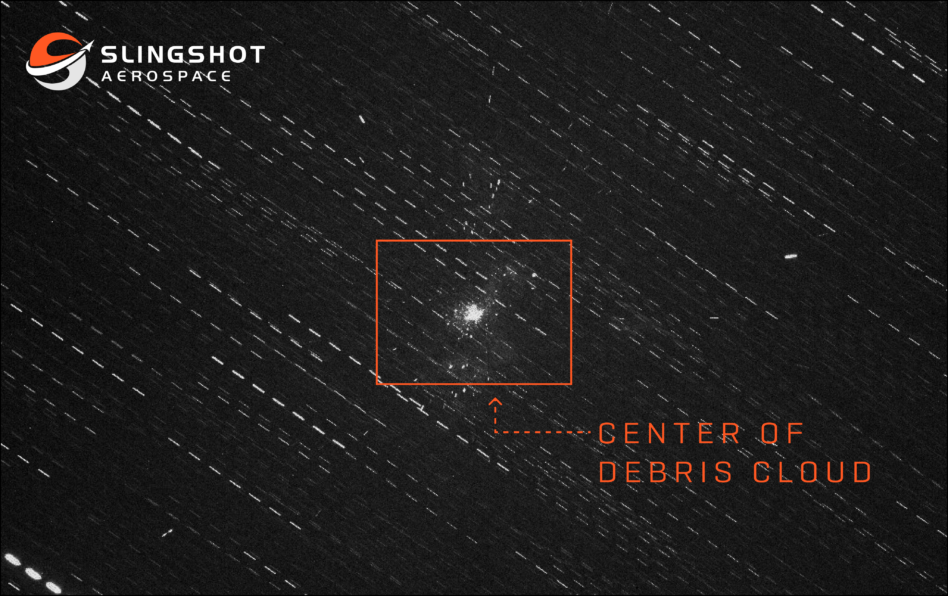

Moment of truth: In Chile, two of Slingshot’s telescopes spotted the stage before and after impact on Sept. 6, sending an automated alert to an analyst. The company is tracking forty pieces of debris from the break-up, which took place in a highly-elliptical orbit. The company is not currently tracking any collision concerns, but the debris cloud will continue to pass through LEO and MEO orbits on its current trajectory.

The Centaur second stage is from an Atlas V rocket, which launched the GOES-18 satellite in 2018. The cause of the break-up is hard to ascertain; ULA CEO Tory Bruno said on social media that the company completely passivates used stages by draining propellants and batteries, which ought to prevent a high-energy event like this one.

Jonathan McDowell, who maintains an exhaustive catalog of space objects, noted that two Centaurs broke up in 2019 and another in 2018, which might suggest that there is more debris and thus more impact in geotransfer orbits than currently understood.

Rocket body problem: In August, a Chinese Long March 6A rocket broke apart in orbit after deploying the initial satellites for the country’s first satcom megaconstellation. China has yet to publicly comment on that debris event, but because of a similar event after a launch in 2022, experts worry that it is a problem with the launch vehicle.

Second stages are typically large and not maneuverable, so they present a particular challenge for debris mitigation. The FAA is considering implementing a rule that would require upper stages to be deorbited within 25 years.

“We absolutely need better rules on disposal of upper stages,” Schaffer told Payload. “Launch vehicle providers need to be deorbiting those upper stages to avoid these collision risks. Or if they’re not able to be deorbited on their own, that’s where the on-orbit servicing and active debris removal capabilities start to come into play.”