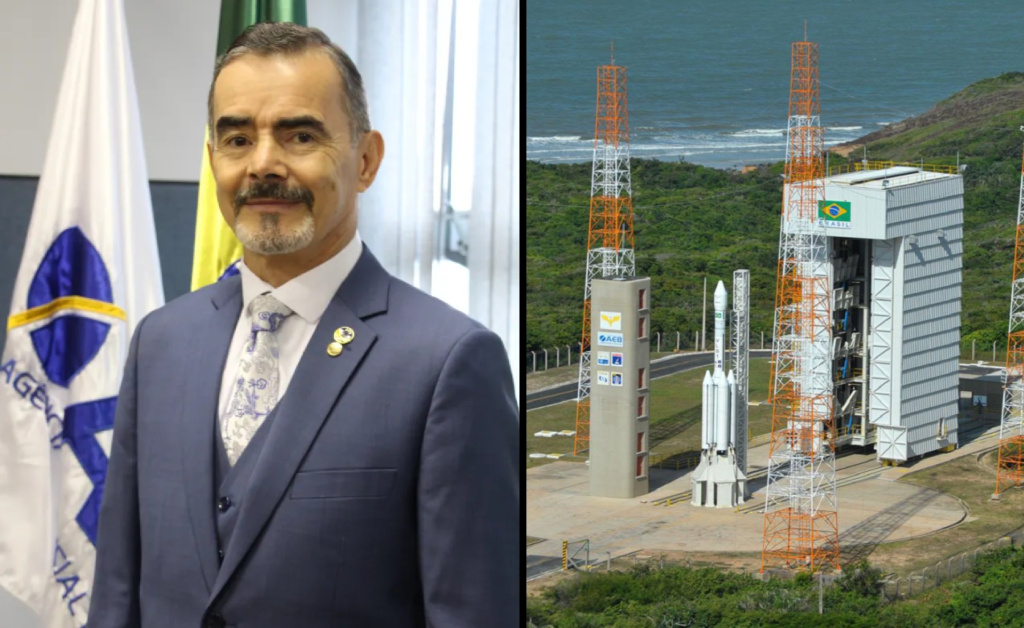

Carlos Moura is president of the Brazilian Space Agency (AEB). In April, we sat down with Moura to discuss the country’s space priorities.

- Last week, Brazil announced an agreement with Innospace, a South Korean rocket startup. Innospace aims to launch the first suborbital test flight of its HANBIT TLV rocket from Brazil’s Alcântara Spaceport in Q4 of this year.

- Next week, AEB will help host an event aimed at promoting space development in Latin America.

- Marcos Pontes, Brazil’s lone astronaut, visited the ISS in 2006. Pontes currently serves as the country’s minister of science, technology, and innovation. Yesterday, Blue Origin announced that a second Brazilian—civil production engineer Victor Correa Hespanha—will soon go to space on the NS-21 flight.

“Brazil is one of the few countries that can act in all segments of space,” Moura told Payload, with a track record in EO, suborbital sounding rockets, microgravity experiments, and ground stations.

- Building off that base: Moura believes Brazil can do a better job in developing domestic downstream space applications for its agribusiness and energy sectors. That’d help Brazil develop its own supply chains and further capitalize on R&D efforts.

- Rocketry: Brazil is developing its own nanosatellite launcher. A sovereign orbital capability “is something that we believe we should have,” Moura said.

- Open for business: AEB and the Brazilian Air Force are in the process of opening up the Alcântara spaceport to foreign launchers.

- To the moon: Brazil, an Artemis signatory, aims to “have a medium- and long-term vision of how we can join the other countries and really participate” in lunar exploration efforts, Moura said.

Find our full conversation with Moura below. NB: This interview was edited for clarity and length.

Walk me through Brazil’s space history.

Brazil has acted in space since the ‘60s, mostly in R&D. I’d say that we are good at suborbital launches, microgravity experiments, and Earth observation. Those are areas where we have already established a market and things that we’re good at. But we should do a lot more.

Brazil is one of the few countries that can act in all segments of space. We can do spacecraft, satellites, and rockets. We can launch from our bases and we have a network of ground stations.

Downstream, we are not as good. Why not? Maybe because our view was to focus on science and technology, but not the business. Now, we are trying to change the mindset. We’re organizing events, including the SpaceBR Show on May 17–19, where we’ll gather the industries, national organizations, academia, government, and defense. We’ll show them that we’re a great consumer of space projects.

Why not take advantage of our whole market and strong economic sectors, like agribusiness, oil & gas, mining? Why can’t we develop applications for them instead of just buying from outside? I believe we are in a good place to invest and find new partnerships, not only for our internal market but as a platform for the whole supply chain.

Are there specific areas of the Brazilian space industry that you want to cultivate in the near-future? As you say, the country has a long history with sounding rockets and EO.

Upstream, I would say that we want to upgrade our capabilities, in terms of rocketry and launch centers. We want to really open our country as a commercial spaceport. We believe we can have the first commercial launch from our country this year. That’s access to space. We’re also developing our nanosatellite launcher, which is something that we believe we should have.

A domestic launch capability?

Yes, at least for nanosatellites and microsatellites.

And which rocket is that?

We have one project that’s being done with Germany called VLM, but we have some other projects on the shelf that we are trying to update. [VLM = Microsatellite Launch Vehicle.]

How about satellites?

We launched one in February 2021—Amazônia 1—with a bus that weighs about 250 kilos. It’s good for small satellites, up to 500–700 kilos. The bus is performing very well, so we’re confident on that.

We believe we can invest more in nanosatellites. To give you an idea, we have 10 nanosatellites being produced in Brazil, coming from academia, small companies, and governments, and a wide range of applications. [Ed. note: Shortly before this conversation in Colorado Springs, the University of Brasilia launched the AlfaCrux satellite on Transporter-4, with mission logistics managed by Exolaunch.]

Concerning applications, we believe agribusiness and energy will be the main consumers. Some institutes in Brazil are mapping our potential, in terms of offshore energy. It’s about 10 times the amount of energy we presently use. We don’t need offshore but it may be used to produce oxygen and hydrogen.

We have some specific niches in Brazil where we can more intensely use [this data]. Because of the war, we may come up short on [agribusiness inputs]. The idea is to reinvest in Brazil in order to produce fertilizers, defensives, like so. And how to use it more efficiently. In this case, space systems can help with more efficient agriculture.

Because you mentioned it, how has the war changed your thinking on space supply chains? Has it affected the agency?

We’ve always advocated that space systems are something that is strategic for the country. We should not depend exclusively on products from the outside. We should have relative sovereignty for our systems. I believe that among our political leaders, we have a better understanding that we should invest a little bit more on our capabilities. We should have our small launcher, and the conditions to produce most of the equipment that can be used to produce nanosatellites.

Understood. Can you say a bit more about the Alcântara Space Center? How badly did I pronounce that?

Alcântara, as you know, is run by the Air Force. It’s not easy for us to adjust [and figure out] how to conform a military station to provide commercial services. The idea is that we should have in the near-future a state-owned company that will act as a commercial entity.

Before that, because the company is not ready, what we are doing as an agency is taking care of all the regulation, licensing, and matchmaking. We’re looking for synergy between the institutions. The Air Force is trying to accomodate this activity.

Alcântara does not have a tough schedule. You have a lot of slots that can be used by everybody. What we are finding is that most of the companies do not need to be in our country for a long time. They want to arrive, use it for a few weeks, and then get out.

Some of them are really planning, if everything goes okay, to invest in their own facilities. That’s why the government and ministries are organizing this, in order to upgrade the infrastructure in the city. The city is very small and very poor, so the infrastructure needs to be upgraded.

There’s an interesting parallel in Texas, where I’m from. In the south, there wasn’t infrastructure in Boca Chica, before SpaceX started building their Starbase. You need the local economy, too.

Yeah, we should help and work together.

Our readers are mostly within the space bubble, but I’d still wager that most of our audience doesn’t know that a Brazilian astronaut [Marcos Pontes] has been to the ISS. What did that mission mean for Brazil, and the space program in particular? I’d imagine it was a huge inspiration.

For sure. All astronauts are [a kind of space] ambassadors. Marcos Pontes is an ambassador and source of inspiration, but he’s also been in the role of minister of science, technology and innovation for three years and three months.

He’s emphasized a lot of things that we should take care of and do in Brazil, and not just in space. Under his leadership, we have 28 institutes in Brazil across many science and technology efforts. So, I believe he has performed very well.

Unfortunately, he was the unique astronaut in Brazil. After him, the Brazilian space program did not have the budget to continue and invest. And we did not take the opportunity to really participate in the construction of the [space] station. By the 1990s, we were supposed to help form some of the parts of the ISS—but we lost a lot of the opportunities.

Now that we have joined Artemis, the idea is to be more consistent with our proposals. We want to have a medium- and long-term vision of how we can join the other countries and really participate in the Artemis efforts. People who go to the moon will need food, rations, logistics, and communication. It’s important for Brazil to participate in those actions and find solutions to challenges that will be presented in the exploration of the moon.

A lot. There’s a lot of logistics.

What we want to do is to call up not only the scientific part of Brazilian capabilities, but the important economic domains—food production, mining—and tell them: “You have a very nice opportunity to explore the moon. How can you join us?”

So that’s what we are trying to do: call the other economic sectors in Brazil and try to show them that they can invest, initially with scientific missions, and eventually take these long-term visions and participate with the other countries.

Glad you mentioned Artemis, that was on my list. Before we close, anything else you’d like to add?

Take the example of Artemis. We already have a project with NASA to develop a nanosatellite to investigate the ionosphere. We proposed, and they accepted, to use the same kind of arrangement to study the climate around the moon. That’s the idea, to continue working together and opening new opportunities. Our work is to get in contact with new people. How can we work together, with NASA, JAXA, and others, to do things under our scope and capabilities?