TOKYO—At Astroscale’s headquarters, the ornate lobby is designed to impress visitors with the futuristic possibilities of space, but also the magnitude of the challenge—in the form of a single red cotton ball among a sea of a few dozen white balls inside a translucent plastic sphere.

Turned on, jets of air send the cotton balls into “orbit” around the globe—and suddenly, any imaginary vision of gentle orbital mechanics is replaced by a chaotic swarm. Can you reach in and grab the red ball—a piece of orbital debris—amid the madness?

Reader, I could not. But as a metaphor for Astroscale’s space sustainability business, the cotton ball tornado works: Not only is the orbital environment more dynamic than many realize, there are also no rules.

Last month in Japan, the Secure World Foundation hosted its sixth annual Summit for Space Sustainability, a gathering of researchers, policymakers, and executives focused on ensuring that the environment around our planet will continue to benefit humanity long term.

It’s no accident that the conversation is happening in Japan—besides Astroscale’s commercial clout, SWF’s director of space security and stability Victoria Samson said there is growing interest in the subject throughout Asia, including initiatives in India, Thailand, and Indonesia. And of course, there’s another major power in the neighborhood—China, with a space program that is vying with the US to be the most capable in the world.

It’s not, however, aiming to be the most sustainable. Chinese rocket bodies frequently fall in neighboring countries. One example: Wahyudi Hasbi, a space official at Indonesia’s national science agency, said launch vehicle stages fall onto his country’s territory frequently. “We have to report this to the country [it] belongs to…so far, there is no answer,” he said.

The silence from one of the biggest national players on the space stage helps sum up the conversations on the panels and behind the scenes: Efforts to manage the space environment, from orbital debris to space traffic to environmental impacts, will depend on the private sector.

It’s the economy, stupid

If that thesis seems strange, given that governments largely manage orbital safety today, with Astroscale and other start-ups carving out space servicing businesses seeking to win their business, consider where the problem came from: Our most pressing concerns about space sustainability hinge on the blossoming of private activity in space, which has led to more assets on orbit, new architectures that rely on swarming spacecraft, and more frequent launch.

Everyone is aware of the tenuous situation where satellite operators rely on informal communications and norms to keep their satellites safe. There’s no existing venue for coordination and management, and while the United Nations is working on it, few expect concrete action in the years ahead.

“There is no such thing as regulation in space traffic, and there won’t be for a while,” Richard Dalbello, the head of the US Office of Space Commerce, said in Tokyo—and he would know. His office is the furthest along in creating the foundation of such a system, called TraCSS, which is being developed with a handful of private space situational awareness firms.

That leaves the real action in the hands of private operators, who at the very least have skin in the game. Just ask Josef Koller, the senior space safety advisor for the $10B+ Amazon Kuiper satellite network. “When you invest such a large number into such infrastructure, sustainability has to be built in from the beginning,” he said.

Chris Blackerby, Astroscale’s COO, puts it more bluntly: “You will not be profitable without incorporating sustainability.”

That’s not just a business strategy, though. To get the wheels of government turning to provide venues for coordination and rules for the satellite agency, experts at the conference argued that an economic framework is the best way to bring governments around.

“We need one narrative that is focused on the economic benefit of what we’re discussing here—economic benefit for the people who will help the sustainability, economic benefit of the space economy as a whole,” Hermann Ludwig Moeller, the director of the European Space Policy Institute, said in Tokyo.

The business of space sustainability

It’s easy to focus on orbital debris as the be-all and end-all of space sustainability, but Dalbello urged stakeholders to think about the “totality of the impact we are having on the environments we visit.” That means space debris, but also the effects of deorbiting satellites, launch vehicle emissions, interference with astronomy, and even junk on the Moon.

For now, though, the private sector centers around two broad business models in the sustainability sector: Space situational awareness, with companies using terrestrial and orbital sensors to gather and market data about what’s going on above the planet, and space servicing, where a handful of companies are deploying vehicles capable of maneuvering safely in close proximity to other spacecraft to refuel or service them in some way.

In Japan, Mitsubishi has taken the lead on space surveillance; the firm is building a new deep space radar for the Japanese government and developing a spacecraft with sensors to monitor other vehicles in geostationary orbit. The American firm LeoLabs is also working with the Japanese government on space situational awareness projects.

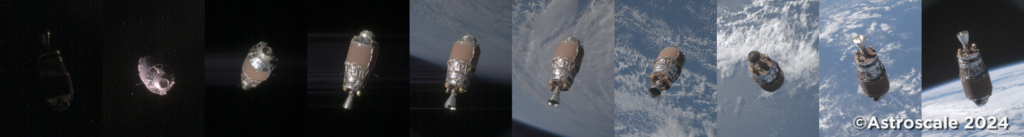

Astroscale is leading the space servicing charge. This week, it released high-res images from its ADRAS-J vehicle, which is on orbit demonstrating the rendezvous and proximity operations technology that’s a first step for active debris removal. It has been circling a derelict Japanese rocket body to understand its motion and how best to pull it down to burn up in orbit. JAXA has hired Astroscale to do just that in the years ahead for an undisclosed price.

Nobu Okada founded Astroscale in 2013, after a mid-life crisis led him to leave a career as a software entrepreneur and look toward his childhood interest in space. At a conference focused on space debris, Okada heard the presenter talking about solutions that could be developed in five years or more. Stunned by the long timelines, he said he realized that the space industry needed a company that could develop technology on the time frames used by private sector start-ups.

The company’s first cubesat was lost on a failed Soyuz launch in 2017, but the next mission, ELSA-D, saw a servicer spacecraft approach and mate with a target spacecraft. That, in turn, fed into the company’s current mission to survey and eventually remove a large piece of orbital junk. The next technical challenge for the company is developing the robotics necessary to grapple with and service active satellites.

“Every day now, we get the question, how do you make money?” Okada said. “Four years ago, our [total] revenue was less than $1M. Since then, we started capturing business opportunities globally.”

Astroscale cites four business lines:

- End of life disposal of satellites

- Removal of debris

- Extending the life of satellites and refueling them

- In-space inspection.

From a capability point of view, Astroscale’s main rival is Northrop Grumman, which operates spacecraft capable of extending the life of GEO comms satellites. But other start-ups have yet to demonstrate RPO tech in the same vein as Astroscale’s.

“We are at the cusp of a booming orbital servicing market.” Okada said. ”I have a clear target: by 2030, we want to make orbital servicing just routine—routine is the point. We believe demand will come because of economics, and also the regulatory environment is getting stricter.”

Who’s regulating who?

The rules for behavior in space have had a direct impact on servicing—many point to the FCC’s five year deorbit rule, enacted in 2022, as an incentive for satellite operators to adopt propulsion systems or other plans for end-of-life disposal.

While that rule was adopted in part because of the massive increase in new spacecraft being approved, many in the industry don’t like that satellite operators are being painted as pernicious. Though SpaceX, the world’s largest satellite operator, didn’t have a presence at the sustainability conference and doesn’t join industry safety coalitions, the firm has a reputation for working closely with other operators on safety issues.

“[If] you spend anywhere from $100K to $300M for a satellite, and anywhere from $200K to $200M to launch that satellite into space, you’re probably not a bad actor,” Chris Kunstadter, the head of AXA XL’s space insurance business, said at the Spacetide conference in Tokyo. “The bad actors in today’s fraught geopolitical world tend to be the nation states that do things that tend to be risky, whether it’s ASAT tests or getting close to a satellite from another nation state.”

When Samson asked a panel of Asian space officials about how they envision coordinating or consulting with China on space safety issues, an awkward minute of silence was followed by laughter from the audience.

“When we talk about global coordination on SSA, we do mean truly global,” the US Office of Commercial Space’s Mariel Borowotiz said in response. “Including China—a major actor in space, with a large number of space objects and planning to put many more up—they have to be a part of the conversation.”

Her boss, Dalbello, compared the current state of affairs to the early days of air traffic control—a guy standing on a runway with two flags. To progress, he says, “we need the governments of the world to figure out how to communicate with each other in near-real time 24 hours a day.” And if that seems like a challenge, you understand why private satellite operators think they’re going it alone.

Fukushima Yasuhito, a space security expert at the Japan National Institute for Defense Studies, said global space governance needs to respond to novel technologies, but worried that global solidarity is too low.

“We are seeing deep division among countries,” he said. “Trust among nations is a foundation to update global space governance. Now after the state of the war in Ukraine, we are seeing deeper divisions, and such divisions are reaching the point where it is not easy to repair.”

Editor’s note: This is the final installment in our series on the Japanese space sector; following deep dives into Japan’s commercial space ecosystem and lunar ambitions.