Exponential growth in the number of rockets launched each year will have a significant impact on society. Just a little over a decade ago, roughly 60 rockets launched over the course of a year—about the same number of planes that take off daily from Napa Valley Airport. Next year, that’s expected to balloon five times that amount, to over 300 launches—the same number of planes that take off every day from LAX.

In addition to the growing launch cadence, spaceflight will also begin to include regular Earth returns. We’ll have to adapt the regulatory regime to keep pace, and one action we can take now is to start defining standardized safety metrics.

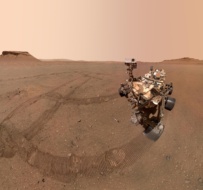

Varda 101: In February, Varda brought a batch of pharmaceuticals processed in microgravity back to Earth—becoming one of only three companies ever to return a spacecraft from orbit.

We were also the first to obtain a reentry license under the FAA’s Part 450 regulation, thanks to close collaboration with the FAA. Varda has another four flights scheduled for 2025 and plans to fly spacecraft every few weeks by 2030, eventually making returning spacecraft to Earth as common as launching rockets.

The problem: The FAA has seen a 1,500% increase in the number of license applications in the last decade. That number—and the resulting long wait times—are only growing. Last month, the House Space & Aeronautics Subcommittee held a hearing on reforms to avoid stagnation of the commercial space industry.

The FAA’s mandate is to focus on public safety, and the long wait times are understandable, given the agency’s current method of reviewing applications. But the cadence is not sustainable if we want the industry to continue to grow.

The FAA calculates the probability of causing a casualty via a bottom-up analysis, bespoke for each application, which includes:

- Every material on the spacecraft

- What time the spacecraft is flying

- Number of people in the region the spacecraft will fly over

- If those people are inside, the material of their roof (a wood roof is more likely to collapse if unintended debris falls on it compared to a cement roof)

- Transient population events such as a local concert at the time of flight (the chances of debris causing a casualty are higher if the spacecraft breaks up over a crowd)

This is the reason why I know that about 20 percent of roofs in Idaho are wooden. I also know there was a Ja Rule concert in Pocatello, Idaho on July 7th, 2023 (with Ashanti opening).

The solution: The review process needs to be augmented with standard safety metrics that are easy to check, so FAA analysts don’t have to start from scratch with every application.

Think of it this way: a traffic officer checks your driving safety via standard safety metrics—the speed limit, functioning tail lights, and so on. The officer does not analyze your probability of causing a casualty via a bottom-up analysis that includes your particular route of travel, the number of kids on the sidewalk, and the material of the buildings on the street every time you go for a drive.

Luckily, there are straightforward standards we can introduce today that will save FAA analysts time by building on existing regulations without sacrificing safety , such as publishing a standard population map approved by an entity such as the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST). NIST already supports federal agencies, including the FAA, by defining standards across industries for just this purpose.

With a pre-approved standard population map, each applicant wouldn’t need to generate their own population exposure analysis, and FAA analysts could save the time currently spent reviewing each one individually. A standard population map could even have a safety margin built into it, like assuming a Ja Rule concert every night.

This is just one example; there are many opportunities to apply standards throughout the application process. The FAA and NIST can work together to start introducing them to make every FAA analyst more efficient. Standards are a near-term improvement that builds the foundation of a long-term solution; generating more licenses without compromising safety.

The existing regulations’ bottom-up approach was valid when launch was nascent, but as the industry matures, defining more standards will allow more companies like Varda to lift industrial operations off our home planet and bring back the goods at scale.

Will Bruey is the CEO of Varda Space Industries, which formulates pharmaceutical products in orbit and supports government partners through its hypersonic testbed. He was formerly a hardware development engineer and mission control operator at SpaceX flying Dragon to the ISS. Will is a pilot who flies his airplane regularly and his great-uncle Elwood “Pete” Quesada was the first administrator of the FAA. You can follow Varda on X (@vardaspace).