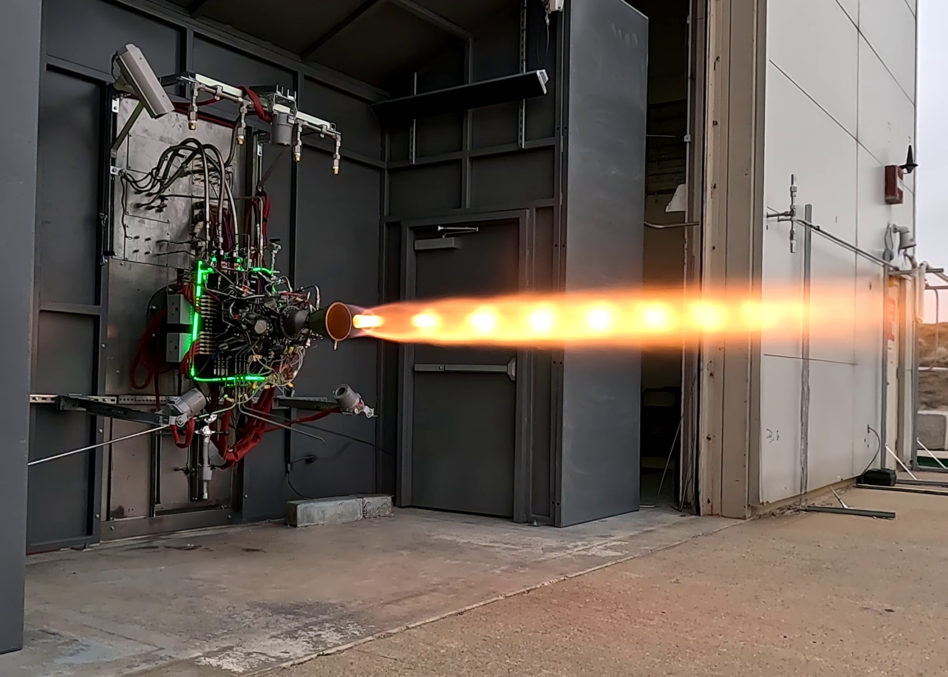

Rocket engines are finicky, particularly new ones, but that isn’t stopping Ursa Major: Engineers have test-fired the startup’s Draper engine more than 50 times since its first ignition in March.

“We went from proof of concept to 50-plus fires on the same engine here in less than a year,” Ursa CEO and founder Joe Laurienti said yesterday on a press call. “It starts to feel more like an aircraft engine development than a rocket engine development.”

Back story: Ursa was founded in 2015 as a dedicated propulsion company focused on national-security applications. Its Hadley engine, which flew for the first time this year on Stratolaunch’s Talon Hypersonic demonstrator, caught DoD’s eye, and the department awarded a contract for the startup to begin building the new Draper engine specifically tailored to the military’s requirements.

“A few years ago AFRL approached us and said, ‘Hey, we see a need for your Hadley engine with storable propellant, what propellants would you use?’” Laurienti explained. “The intent of this contract was initially to design, build, and verify operability of the engine architecture, obviously with 50 plus tests we’ve gone well beyond that.”

The engine is designed to produce 4,000 lbf at sea level, and utilizes kerosene and hydrogen peroxide as storable and safe-to-handle propellants. Its most novel feature, Laurienti said, is its ability to throttle—it can even switch to a monopropellant mode that only burns hydrogen peroxide, allowing it to reach below 10% of its maximum power. What’s all that good for?

- Vehicles that have to fly at a moment’s notice, like missile interceptors

- Aerial targets for hypersonic weapons tests

- High impulse transfers between orbits and orbital insertions

Laurienti said that he was surprised by incoming interest in the engine from a US combatant command and for in-space activities.

Make or break: Draper’s heritage from the Hadley engine gives the company confidence that it can reach a production cadence of one engine per week. The biggest bottleneck for the engine right now, Laurienti said, is simply time on the test stand. He expects to qualify the engine for production in 2025 ahead of first flights in 2026.

RDRE alert: The CEO also dropped a hint about the future: “Rotating detonating rocket engines are an in vogue technology that Draper is certainly very well suited for.”

Correction: This story has been updated to fix the spelling of Ursa Major CEO Joe Laurienti’s name.