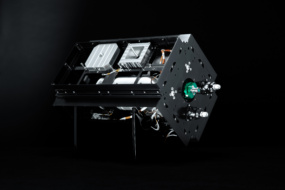

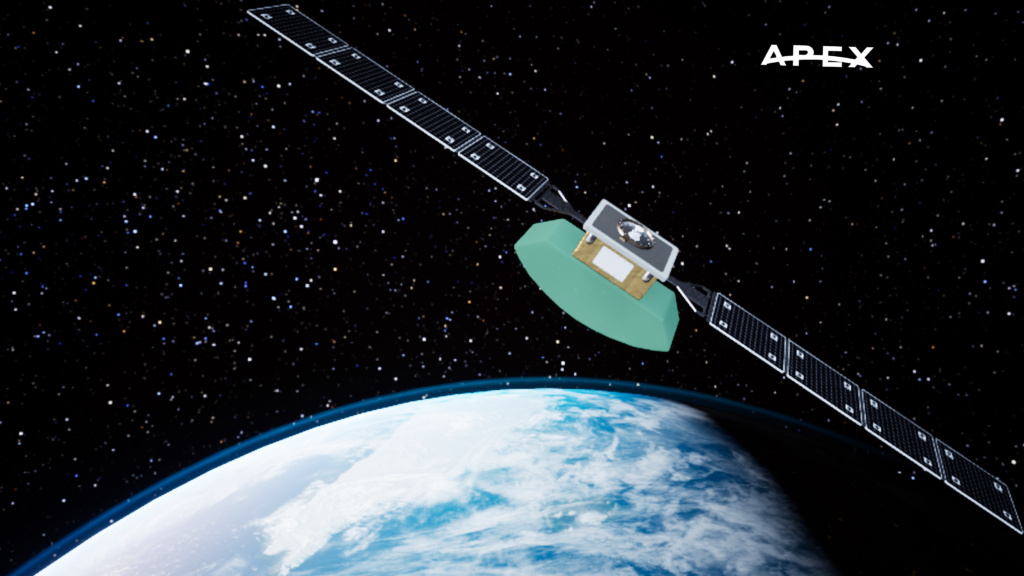

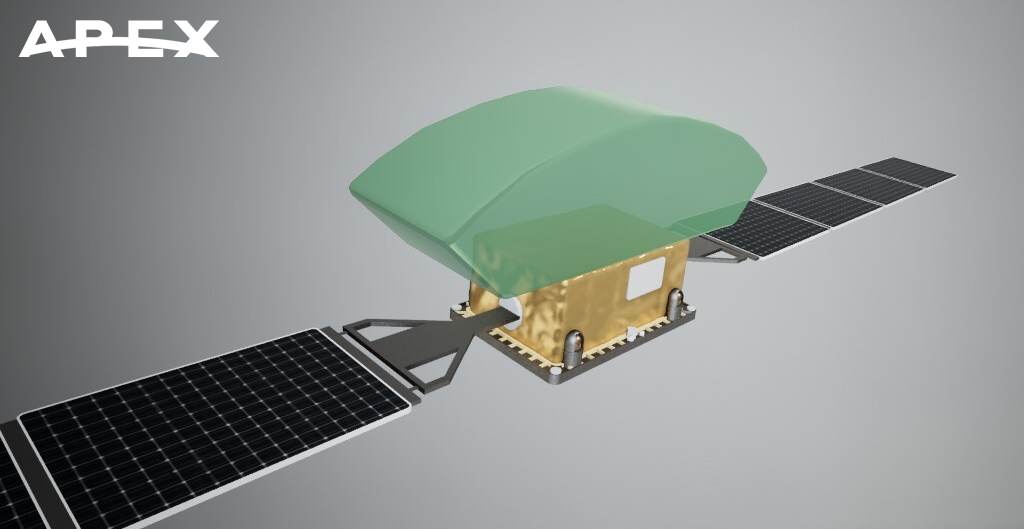

Apex recently announced itself to the world with a $7.5M seed round led by Andreessen Horowitz. The startup seeks to manufacture 100-kilogram class satellite buses that can support ~100 kg of payload. Its first product is called Aries.

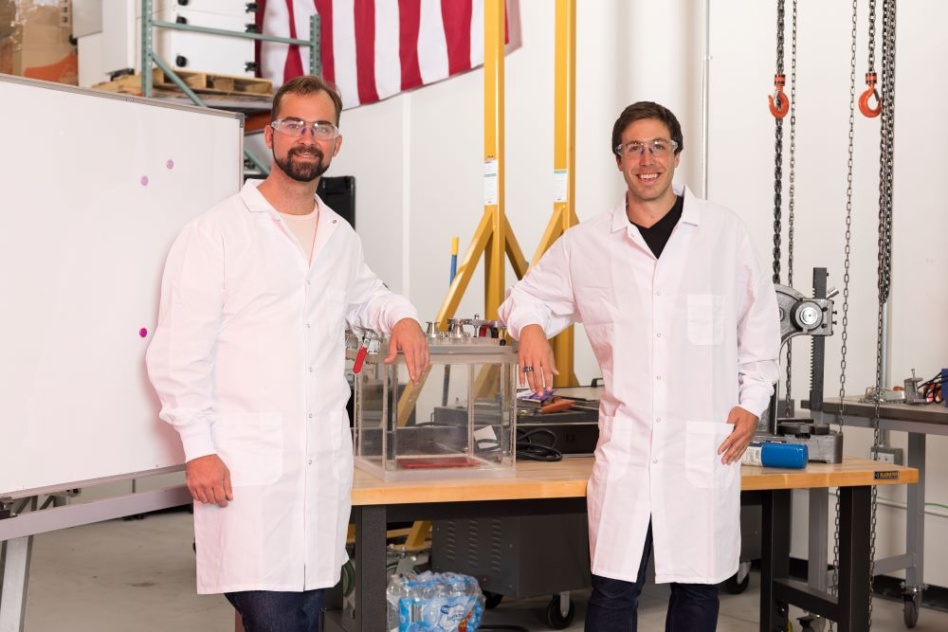

Last month, Payload caught up with Apex Cofounder and CEO Ian Cinnamon. He previously founded Synapse, a computer vision startup that exited to Palantir ~2.5 years ago. He also worked at LA venture fund Village Global as an investor and entrepreneur in residence. Max Benassi, Apex’s other cofounder, formerly built vehicles at SpaceX and served as Astra’s director of engineering.

We recently caught up with Apex’s Ian Cinnamon to discuss why the startup believes the satellite bus sector is ripe for disruption. In the convo, we also cover the company’s recruiting plans, whether Apex’s first Aries prototype is fully funded, when the company plans to start generating revenue, and newsier items, like AEI’s acquisition of a majority stake in York and Lockheed’s $100M investment in Terran Orbital.

NB: Payload edited this Q+A for clarity and length.

What’s Apex’s origin story?

At Palantir, I was asked to basically take the computer vision platform that we built and apply it to downstream satellite data. And that data was all coming from commercial companies, so for me, it was incredible. This market is really growing, and it’s not just government buyers.

I’ve always been under the impression, though, that commercial access to space really wasn’t a thing. As part of my work at Palantir, I really spent a lot of time getting to know these different satellite companies. What I quickly realized was that most of them are payload companies. They’re good at making a camera, sensor, or imaging device, and really good at getting that data down and selling it.

But the spacecraft itself—or the satellite bus—is somewhat of an afterthought. And in this industry, there’s really two ways to go about procuring the satellite bus. You either build it or buy it.

Let’s start with buying it.

There’s effectively two types of people. You could buy it from one of your traditional government contractors: Millennium, York Space, Boeing, Airbus, SSL, Maxar…these types of companies. They sell commercially, sure, but their primary business is government contracting.

Or you can go to one of the more agile R&D firms. The scary thing is there’s only one in the US and that’s Astro Digital. Then, there’s several overseas: NanoAvionics, EnduroSat, and AAC Clyde. They do a really good job and try to be agile, but what we’ve noticed from chatting with their customers is that they tend to focus more on the cubesat platform. They’ll occasionally stretch up into small sats, but it’s not really their bread and butter.

Because of that, every time they’re producing a small satellite in our size class, the end customers feel like it’s really being custom-built around their payload. Historically, that used to make sense. If it costs you $10M to launch a satellite, you want to minimize the mass of it and get the cost as low as possible. It’s worth it to spend $10M to make a custom satellite bus around your satellite.

But that’s changed in the last several years. There’s been hundreds of billions of dollars that have been invested into launch companies, which massively reduced the cost of launch. The result of that is if you go book a rideshare right now on SpaceX’s website, they will charge you the exact same amount of money for 150 kg as they do for 200 kg.

Mass is no longer directly coupled to cost. It’s now a combo of mass plus volume. They’re getting more creative in pricing. You no longer need your satellite bus to be custom-built to wrap around your payload, and can start to think about making it more of a repeatable platform. So, we think we’re at an inflection point in the industry thanks to that.

What about building the bus?

If you build it in house yourself, it’s expensive. And it takes time—usually about two years minimum for a bus development program. It’s going to cost you at least $15M. What’s worse is once you do that, you have basically all of this dead time. All this amazing engineering talent who just built the bus…and it’s like: “Great, now what?”

What we’ve noticed from chatting with all the customers in our size class is this major trend towards these larger satellite platforms. Larger, but they’re still considered small: 100-200 kg buses. As part of that, there’s a strong desire to solve for three major variables

- Speed of delivery of the bus. Right now, the time you might get quotes is 12 or 18 months, but realistically it’s three to five years to get your satellite.

- Reliability. If you’re gonna wait that long and spend millions of dollars, it better work when it gets to orbit.

- The actual cost. Is there transparent pricing you can rely on later?

Fundamentally, we are arguably the first spacecraft manufacturer–and I really focus on the word manufacturer. I love all of the players in this industry and they’ve done an amazing job. But I’d argue that most people building satellites are doing hand-made designs, custom for each customer.

We want to manufacture satellites. The analogy I like to make is an automotive manufacturer. When you go buy a Toyota Corolla, it’s mass-manufactured, but each Corolla has a set of options you could choose from, from radios to seat warmers to exterior color or whatever. But it’s all coming off the same manufacturing line.

We think buses should be built the same way, where we’ll have a fundamental platform but will let end customers configure each option to their exact mission needs. Configured buses off the same common platform, with the goal of more standardization in the industry.

I don’t want to say too much about the secret sauce, but at a very high level, it comes down to better software throughout the entire process.

When you’re talking to friends or family who aren’t in space, what’s the Earthly object you compare your archetype satellite to, in terms of size or weight? Every company has one.

It’s like a refrigerator.

Not a college dorm room one, right?

Not like a mini fridge. It’s a refrigerator. Maybe this helps more…you can think of the bus itself as a dishwasher or mini fridge, and then the payload our customers stick on top of it is another dishwasher or mini fridge. But they could also have a much smaller payload—there’s variance in what they install.

Who is in this size class? Who’s the target market, in terms of end users, right now?

Because we’re not custom building for each customer, we will say no to customers. We’re commercial-focused, so we’ll say no to government programs not directly in line with our focus. But we’ll say yes to ones that are. With that in mind, we’re starting with LEO customers focused on different forms of Earth observation or communications.

Can you say a little more about the production model? In my mind, I kept returning to the word “scalability,” since you’re not building bespoke products. But how is your model configured for that scalability?

So, what I will say, just to be very clear here, is that we reluctantly say mass manufacturing or scalability. The reason I occasionally shy away from those words is that people think in their head: “Oh, iPhones are mass-produced.” I don’t know the number off the top of my head, but it’s a lot more iPhones being made.

A few orders of magnitude.

Yeah, exactly. It’s just very different. So I tend to be a little bit cautious with those words, which is why you may have seen me skirt around it.

Fair enough. What’s the upper bound, then, of buses that can be manufactured?

We have to be realistic about the market. I think there’s absolutely demand for selling hundreds of these per year, and eventually scaling into the thousands, but we’re not producing millions of these per year, right? There’s a couple zeros we have to slash off there.

In terms of the design, one of the fundamental things is that we’re not inventing something new or trying to convince customers to switch over to some crazy new architecture. We’re just trying to make it much easier and simpler, and standardize how it’s done.

Again, we’re not reinventing the wheel here. We’re simply taking the best practices from the automotive manufacturing world, and frankly SpaceX’s model as well, given their ability to produce engines and Falcon 9s at the scale they do.

Fundamentally, you need to design the physical structure of the bus to be something that is not reliant on a serial path. You can’t go build one element, then go build another, then build this other one. You basically need to design it from the beginning to be a parallel track. At the end of the day, it’s about eliminating a lot of the hand-made nature of these processes.

Would you say the biggest bottlenecks in your early customers—EO, communications—is the cost of manufacturing, integrating, and assembling everything on their spacecraft?

I would argue it used to be the launch cost. Now, the biggest issue for them isn’t the cost of the buses, I’d argue. It’s the timeline and reliability to get them at the scale they need.

Take an arbitrary Earth observation customer. Let’s say they have a constellation of 100 satellites. Those satellites have a mean lifetime of five years. And they didn’t launch all 100 at once, right? What that means is they have 20 satellites per year that they need to constantly be launching because they’re losing 20 satellites a year.

Now imagine you’re having issues with an unreliable supply chain on your bus side, because they’re not all being manufactured. What that very quickly means is your constellation begins to degrade in quality and you start losing revenue that would have been coming off those satellites.

We’ve seen a very interesting dynamic in the industry, which is that cost is not the primary driver. It’s honoring the timeline that’s quoted. Now, of course cost is important.

We’re not trying to go say that we want to be a $100M bus. We want to price ourselves competitively and at a reasonable price point in the industry. But our goal isn’t to undercut—it’s to be the manufacturer.

To what extent are timeline issues evergreen or timeless? In recent years, there’s been all these force-majeure-type events, from Covid to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

So, you’re 100% spot on, it’s definitely been exacerbated by all of that. But even if you rewind before, that’s just the nature of these buses being handmade. There’s fundamental time limitations.

Let’s say you’re launching Ryan’s new constellation. You invented a brand new camera and you want to install it on a bunch of buses. Next step, you go find someone to sell you buses. I’d love to see someone do this faster, but from what we’ve seen, it will take you a minimum of a month to even get quotes on prices from current providers.

That’s not because they’re lazy or moving slowly, it’s because you have to hop on multiple phone calls with their engineering team so they can review your requirements, then go back and spec something up. The RFP process takes a minimum of a month, if not several months. We’ve seen multiple customers go through a three- to six-month-long RFP process.

Our vision is to deliver a bus in the time it traditionally takes someone to get a quote.

SpaceX pioneered the upfront, transparent pricing process with Falcon 9. How close do you want to get to that model, where it’s just listed on the website?

That’s where we want to get to. In the same way, you can book a rideshare on SpaceX and select the options you need. We don’t want to make people go through an NDA process to view pricing or specifications. We want to be as transparent and upfront as possible.

Returning to buy vs build, how vertically integrated do you want to get? What will be in-house vs. off-the-shelf?

It’s not feasible to just say: “Hey, we want to go vertically integrate everything.” And we’re not believers in vertical integration just for the sake of vertical integration. The way we see this market is that for every sub-assembly component, there’s going to be a build vs. buy study that has to be done to understand the efficiencies that we could win on.

We need to be able to have a robust and reliable supply chain, and be able to swap components in and out because someone might have a shortage. So, we’re very open and want to work with partners. We’re not trying to do it all in house. If partners are able to support a robust supply chain, we’re very excited to work with them.

If you’re successful, are you going to compete with customers? Or stay agnostic?

No. Our goal is to be a provider for customers who have specialties in the payload. We’re downstream of their payload, and want it to make it as easy as possible for them to get to space. We’re not building a constellation or developing a crazy camera. Win within your wheelhouse and then help others win as well.

A rising tide lifts all boats. Turning to the news of the day, where does your seed round get you? Choose whatever metric you like: progress towards the first prototype, runway, or something else.

Bringing on the right team is incredibly important to us. This lets us staff up and get to heritage with our very first bus and prove that to customers. It will also help us prove out a lot of our assumptions around the scalability of our manufacturing process.

You can kind of back into what your prices will be, then, if it gets you to the first bus. Right?

I don’t want to say something and then be wrong down the road, but we’re trying to be transparent with our pricing. We also believe that in addition to the funding, that we have revenue we have a clear line of sight on.

With just $8M alone, it’d be pretty hard to get to flight heritage. There’s other revenue that’s coming in that’s supportive of that heritage mission. We’re exploring things on the government side, as well, that will let us achieve those goals.

It’s rare to hear from a space startup that they’ll generate revenue that early on. Even rarer to actually see it happen in reality.

You want to be able to show revenue early and show a strong business, and you want to take in revenue frankly that pushes your mission forward, and revenue that’s not a distraction. We’re not going to go do some weird consulting work or build a bus that’s not directly aligned with what we’re already making.

How’d you link up with Max, your cofounder?

Funny story. We met several years ago. At the time, Max was actually working at SpaceX. His roommate in LA was my friend from high school and happens to be like the #1 aerospace recruiter. He’s worked for all the major companies you could imagine. When Max went to Astra, he realized that launch was moving in a direction of being solved. What’s the next frontier? There’s all the money that’s gone into launch and payload companies, but buses have not received a lot of attention.

Editor’s note: Payload caught up with Cinnamon after this initial interview to ask a few additional questions related to newsy developments. We’re including that portion of the conversation below.

What would you say about Redwire taking a majority stake in York, at a reported valuation of $1.125B? How does this reinforce or refute Apex’s thesis?

This very much reinforces Apex’s thesis—the biggest area in space ripe for innovation is the bus side of the market. There is far more demand than supply, and as a society, we need to be moving faster. So, seeing York have a capital infusion to move faster is incredibly positive for our thesis and for the industry as a whole. We are rooting for York and look forward to seeing them continuing to push forward on their expert work with the US government and SDA.

What about Lockheed Martin’s just-announced $100M investment in Terran Orbital, upping its stake to ~33% of the company?

Lockheed’s major investment into Terran Orbital is another reinforcement of the Apex business case. It’s great to see traditional bus manufacturers getting attention and capital to meet the growing demand, especially given Terran’s depth of expertise working with the US government and the ever-growing demand for more buses.

Ultimately, what do these recent deals reveal about the US bus and satellite manufacturing sector?

These recent deals prove that demand is booming and we need to double down—or triple down—on manufacturing spacecraft.

Not only is Apex doing just that but we are also focusing on scale—pioneering configurable systems that minimize new NRE while maintaining flight heritage and reliability. Our mission is industry-leading delivery times, lower cost, and high reliability. We are uniquely positioned to serve the huge demand from the commercial space sector—as well as the government sector.

Launch continues to improve and costs are dropping. It’s time for bus manufacturers to start lowering the barriers of entry to space.