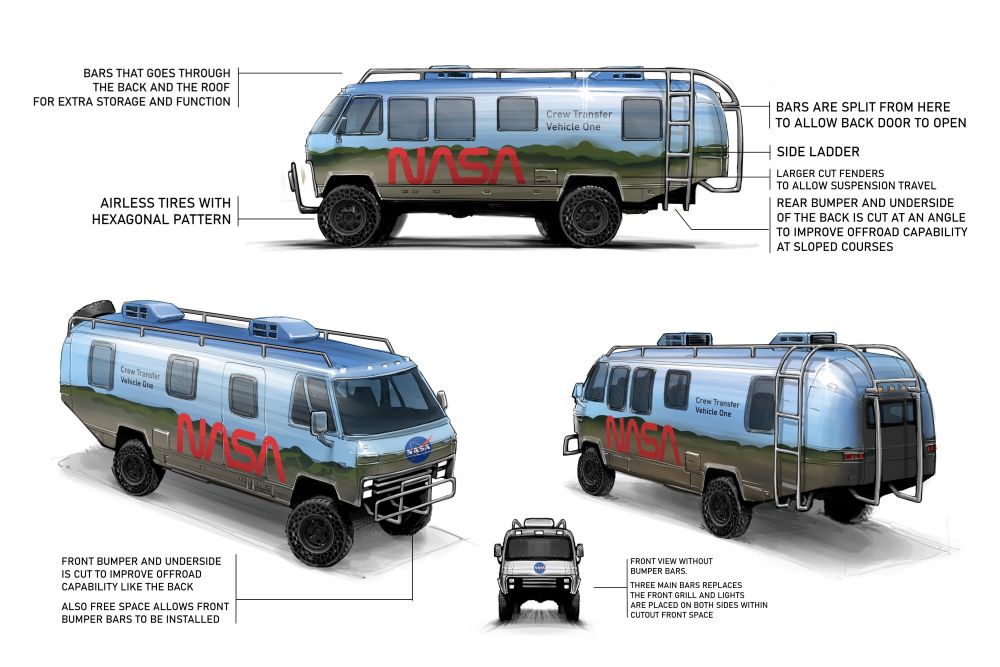

Render for an Artemis-era crew transport vehicle. Image: Oxcart Assembly.

NASA recently awarded electric vehicle developer Canoo ($GOEV) a $147,855 contract to produce the crew transport vehicles (CTVs) that will ferry Artemis crews nine miles from their astronaut quarters to the pad in Cape Canaveral. The CTVs, as specced by NASA, must be zero-emission vehicles, fit eight people, including a crew of four fully suited astronauts, and contain nearly 60 cubic feet of cargo storage.

The CTV award didn’t draw much attention because it was small peanuts, relatively speaking, as far as contracts go. It’s why primes and other major names may have not been inclined to place a bid. Plus, spaceflight players these days tend to have their own transportation arrangements to the pad: SpaceX uses Teslas and Blue Origin relies on Rivians. Meanwhile, Boeing has Astrovan II for eventual Starliner crews.

Still, the award could be viewed as a loss leader for brand-building, given the amount of eyeballs and attention that will be on American astronauts’ return to the Moon. “We anticipate billions of impressions associated with the Artemis program,” Canoo CEO Tony Aquila said. The CTV runner-up bidder, who we’ll meet in a second, tells Payload it would have lost money producing its vehicles—and that the contract “was always a content play, financially.”

There’s a catch

In its earnings report this week, Canoo conceded that it’s in big trouble. The company issued a going concern warning and isn’t confident it can reach volume manufacturing without a large capital infusion. It lost $125M in Q1 of 2022, vs. $15M from the same period a year before, and ended March with $105M in cash on hand.

- What’s more, Canoo has filed a lawsuit against its second largest shareholder, DD Global Holdings, an investment firm with ties to the Chinese government, over suspicious share sales, Bloomberg reported. Canoo is seeking to recoup $61M+ in “short-swing profits.”

- “Canoo is alleging that, as of March 15, 2022, DD Global remained the beneficial owner of more than 10% of Canoo’s total outstanding common stock, which would put it in violation of the national security agreement,” per TechCrunch.

- In Dec. 2020, Canoo and CFIUS entered into a national security agreement to limit the “control and governance influence of DD Global.” CFIUS is an influential, interagency US government panel that reviews deals involving foreign investors for national security risks.

I’m building a team

Oxcart Assembly, a self-described “decentralized group of creatives, dreamers, and entrepreneurs,” spearheaded a coalition that also bid on the CTV contract. The design agency pulled together a group that included Hoonigan Industries, Airstream, IBM, and Red Hat.

- Hoonigan, an automotive media group, and Airstream brought their car smarts and experience to the table. Airstream has a history with NASA, as it built three modified Excella motorhomes for the Shuttle program.

- IBM and Red Hat pitched in on “human-centered” design and UX (user experience) research, conducting interviews with former astronauts.

So close, yet so far: Ultimately, Oxcart says Canoo underbid it by $1,145 on the contract. In April, we spoke with Oxcart’s Jeff Jetton about the runner-up’s proposal, the intricacies of the crew transport contract process, and losing a road race to a canoo. Find the full conversation, which was edited for clarity and length, below.

How did your engagement with this proposal begin?

Oxcart had been doing graphics and design work for NASA, starting back in March 2020. We had been in talks with Hoonigan for a different project, looking at the NASA Standards Manual, and nerding out about old illustrations of a NASA Cargo Van.

Folks at NASA mentioned to us that one of the old Airstream Astrovans was sitting in the parking lot at Kennedy Space Center, gathering rust and basically rotting away. I believe a family of racoons may or may not live inside it.

That got our minds racing around the potential of rebuilding it as an EV for the Artemis missions. Hoonigan Founder Brian Scotto and our team put together a document that demonstrated the idea, and we surfaced it to some NASA folks as an unsolicited synopsis.

Our intention at that point was to procure the vehicle from NASA at no charge to the agency, rebuild it from the ground up with an electric motor, and create content: a design/build show. This would culminate in the triumphant return of the vehicle to KSC, ahead of the Artemis-2, to be used as the CTV for subsequent crewed missions.

We learned at the time that NASA’s current plan for returning astronauts to the launchpad was to use a hotel shuttle-type bus with a wrap of NASA branding. We thought there should be a more high-profile and noble conveyance, focused on mission goals of sustainability and adaptive reuse. Which is why we suggested focusing on a rebuild with an EV motor. We cannot speak to where and what internal processes and conversations were had within NASA in regards to our submitted document. We were told that NASA folks were excited by the idea, but that processes for unsolicited proposals are documented and formalized, and that we should look into understanding those pathways and formally submit through the proper channels.

What was the bid process like?

At the stage that the NASA RFQ came out [January 2022], we understood that the government was no longer interested in a rebuild of the current vehicle(s). At this point they wanted a new custom vehicle, developed by a team with significant past performance in a Price/Performance tradeoff (PPTO) solicitation.

This was a surprise to our team, as we were proposing adaptive reuse of the existing historic vehicle with EV technologies, at a significant savings to the government. The vehicle would be as technologically advanced as anything on the road currently but would retain the intrinsic history of prior programs.

The CTV is by nature custom. EV technologies are just emerging to the point of being able to satisfy this type of requirement. The government was also considering a multiple-vehicle scenario that would separate the astronauts into individual vehicles in a caravan, similar to what SpaceX was doing with Tesla.

As it happened, Airstream and [parent company] Thor Industries were imminently preparing to announce a slate of EV technology for their trailers and motorhomes. We began re-thinking our entire model to create a ground-up new-build vehicle based off the chassis and drivetrain of the Astrovans, which Airstream no longer makes. We would incorporate these EV technologies, which are still under wraps, and tap Wheel Pros’ [Hoonigan’s parent company] technologies around airless tires.

We were also wrapping our heads around designing interiors and specifications that focused on the astronaut and their needs in a critical period of time in the user experience journey. When you think about that journey from Astronaut quarters to the pad, this is one of the lowest-risk portions of the journey. Astronauts are not on the rocket yet. They’re not launching, nor in flight, nor in space. They aren’t landing on the moon or coming back. It’s just a nine-mile road trip. We totally get that. However, it is the first leg of the journey and still mission critical to the overall timeline. There is zero margin for error even in a car ride. Not a battery, tire, or anything.

How did Airstream fit into the mix?

As talks and ideas with Hoonigan progressed, we were collectively thinking and ideating around the notion of using Airstream vehicles, but without having spoken with anyone at Airstream. We dove deep into the history of Airstream as a NASA provider.

We were eventually informed that NASA would not accept an unsolicited proposal for this project, that they had decided to bid the project out as an RFP. As we had been ideating on this project for quite some time and had a concept that was highly beneficial to the org, we were confident that this would be the perfect solution for NASA and welcomed an RFP process to determine the best value for the government.

An RFI phase was enacted, a government contracting official reached out to speak with interested vendors about the project and we ended up getting in touch with the Airstream team through that RFI phase process. Naturally, there was a meeting of the minds, given the Hoonigan name and the previous design and branding work that Oxcart had done with NASA as well as the sketches/conceptual imagery we had already designed.

Did you see this as a David v Goliath type scenario, given the profile of the typical companies that win NASA contracts?

Yes and no. It was very specific. Is Oxcart Assembly David? Is Canoo Goliath? Are Airstream, IBM, and Oxcart Goliath? By their own admission, Canoo has no experience to date in high volume manufacture of EVs. We’ve done a lot of work for NASA. I guess the ‘we’ of Airstream/IBM/OA/Hoonigan with Airstream as the incumbent CTV provider for 60 years or more, counting Mobile Quarantine Facilities (MQFs), could be considered a Goliath. We specifically set out to build a world-class team that could meet the narrow challenge, but not necessarily a Goliath. In reality, this was a small team of design-minded folks trying to do something cool and interesting with purpose.

David, in your analogy, would then be Canoo? They went to market with a SPAC recently, so they are a publicly traded company and I’m sure they are well-resourced, from looking at their publicly available information and the amount of lobbying efforts and teams that went into their proposal on their end.

But that’s just Monday morning quarterbacking. We try not to dig into Biblical references for framing our position in the market, for the most part. When does that end well?

What were the key design philosophies and principles that went into the design of this transport vehicle?

Human-centered design, historical research, and UX. We connected with the human-centered design teams at IBM and Red Hat to develop surveys and research questionnaires to get into the mind of the user [i.e., the astronauts].

Oxcart reached out and developed a team with unmatched experience, both relevant and recent. A kick-a** set of design renders that incorporated 60 years of thinking and knowledge in the exact arena of CTV design and production. A history across the board of fulfilling NASA contracts and subcontracts. For Airstream watch the CNN doc on the Mobile Quarantine. Look at the quotes from the astronauts about the existing Astrovans on NASA’s website. IBM. Watch Hidden Figures. The bench was deep. The proposal was specifically focused on human-centered design and taking into account the astronaut experience.

We were designing also with a mindset of ‘what would we want to ride to glory in’. Right? Like what would look f***ing. bad. a**? You’re about to get on a rocket to go to the moon. You want people to high-five as you drive past them as you’re listening to Sepultura on your headphones. It is gameday. Stakes are high. The environment you’re in should reflect that and enhance that experience. Every detail should be meticulously thought out. For all we know, the awardee went through similar processes in their design thinking.

How would you describe the ~vibe~ of your proposal? Retro meets Artemis, with some steampunk tones…is that directionally accurate or a whiff?

Oh jeez, that’s an interesting question. Never thought of it like that. I think we were inspired by the Hoonigan Microsoft Warthog project, a little bit of #vanlife Instagram stylings, and obviously the Shuttle-era Astrovan as the base concept.

It’s a delicate balance designing around what we think the future holds and paying tribute to what got us here. Our business partner, Tony Gardner, designed the Daft Punk robots, and that’s always an inspiration for not falling too far into retro-futurism but pulling off a fun and hopeful outlook on modernism and the stylings of the way we want things to be.

In terms of ‘branding’, due to past design/branding work with NASA, we’re well aware of every aspect of the political football that is the Worm and the Meatball. We live and die by the standards manuals. In fact, we wrote the style guide for Launch America and developed NASA Television’s branding and media package, which is the basis of what the Artemis broadcasts will be based on. We tried to impart that background into ideation around how the Artemis and NASA marks live on the vehicle.

Would you have broken even on this project? Or lost money?

The margin on a bottom-dollar price solicitation for one or three vehicles wouldn’t necessarily justify the costs to a) win the proposal or b) produce one-offs. Our reasoning and thought behind this was always a content play, financially. We offered to just take the existing vehicles at KSC for free and upgrade and electrify them with the intent of making the most bad-a** design & build, road-trip Artemis STEM show ever put on television and then return them well ahead of schedule.

We’d be done with the project by now if we had our way and you could be watching the story on a streaming platform rather than reading about it. The cost to make the vehicle would have been built into production. Hoonigan is one of the largest automotive content providers in the world. Look at their Gymkhana series or Amazon Prime show.

We cannot speak for the winning team but our guess is that certainly they’ll operate at a loss to meet this contract, if they even can meet it. That’s for investigative journalists to look into. And about all we’ll say about that.

From the initial mockups to getting to the finalist stage with NASA, what percent of the way “there” would you say you were? “There” = handing off the ready to go vehicles to NASA within the timeframe specified in the contract…

Look at Hoonigan’s YouTube page. Note the depth and efficiency of their design builds. They’ve got billions of views from people in awe of what they do. Look at Airstream. The proof is in the pudding. This wasn’t a vaporware proposal.

At Oxcart, we have a history of completing projects for NASA ahead of schedule and exceeding expectations. We manage projects efficiently AF, probably because we have something to prove and a desire to punch way above our weight. We recognize that working on NASA projects is about as big a stage as you can get, so we want to impress the hell out of people. You also sort of feel some civic duty or something when you’re working on these types of projects. You’re working, indirectly, for the American taxpayer. And, in essence, for all humankind, although that sounds kinda lame when you say it out loud.

Short answer: we could be there as fast as we need to be. Significantly ahead of any published timeline. Still could.

I’m surprised someone didn’t come in with like a $50k offer, lowballing everyone else and knowing they’d be eating a lot of the cost, but trading that off for the publicity and free media.

We did. But nobody wanted our low-ball offer of zero dollars to do the project.

In terms of ‘past performance’, there is no comparison. From the MQFs of the Apollo era to the Astrovans and Mobile Command Modules of the Shuttle Era, to Boeing Astrovan II to SpaceX and Blue Origin astronaut facilities, there is literally no comparable past performance record for CTVs. Airstream has been the sole provider for the most part. Certainly, Tesla and Land Rover and others would be worthy competitors given their backgrounds with EV and multi-vehicle options for commercial spaceflight providers. However this was a specific, narrow solicitation that would not be revenue-producing at scale.

It’d be a buzzworthy initiative for any provider and probably nothing more.

We were willing to do it at no-cost to NASA to begin with. Our RFQ pricing was based around what seemed ‘reasonable’ and provided in a manner so as to not raise flags around being too low, as price ‘reasonableness’ is a consideration. It’s a tightrope to walk. We didn’t need the government’s money to make the project profitable because we had a financial model that didn’t rely on their money to begin with. We were handing NASA a homerun and a slam dunk on a tee.

One thing we were not willing to do, however, was hire a team of government lobbyists and insiders to shake hands and do whatever it is that corporate interest groups do. Not that we’re holier than thou, we just don’t think that’s an effective use of shareholder, government or our funds.

What can you say about being so close to winning? Being underbid by less than $1,200?

We were not told when to expect a decision and basically waited. We were blindsided a few weeks ago to see an announcement that another company, which was never even on our radar, had won the award by an amount of $1,145 less than our proposed bid.

I’m not going to lie, this immediately raised alarm bells for every single person on our team. Somehow, an upstart that has never created a vehicle off an assembly line, with a host of red flags, including SEC investigations, and an as-of-yet inability to develop production vehicles won the day. I’ll just say we were surprised. But I will also say that we weren’t willing to risk our reputation by formally protesting the decision and potentially delaying the project to the point of creating a timeline crunch that made the entire CTV project untenable. We had every right to do that, it just didn’t seem worth it. Sometimes the ref makes a bad call at the end of the game. What can you do? They had a slightly lower price. We don’t deny that.

It is our understanding of the situation after several conversations with the contracting office that, long story short, it came down to the Performance/Price tradeoff between our team, the awardee and one other ‘major automotive company’ who were ‘qualified’ by meeting all of the technical requirements of the RFQ. Of those, it was between us and the awardee. While I disagree with the measurement of past performance weighting of whatever formula was used to calculate the trade-off, if there was one, the bottom line is that NASA was convinced that the awardee’s past performance merited qualification to evaluate the two proposers heavily on price.

Basically, all things being equal, it came down to that $1,145 difference.