Interlune, a space resources company that raised $15.6M last month, has revealed what the money’s for: It’s targeting the extraction of He-3, a rare isotope of Helium, from the lunar surface.

Schmitt happens: Apollo astronaut Harrison Schmitt, who is a member of Interlune’s founding team, has spent the last four decades calling on people to retrieveHe-3 from the Moon, notably in a 2006 book. Now, Interlune is trying to bring his call to action to life.

He-3 is mainly used in security and medical sensors to detect radiation, but it could theoretically be used as fuel for a nuclear fusion power plant. Mainly sourced from the US nuclear weapons program, the substance does not occur naturally on Earth, but scientists expect it to be plentiful on the Moon, where it is deposited by solar wind.

Moon shot: The size of the current global market for He-3 is difficult to estimate, but analysts suggest it is hundreds of millions of dollars, which also might be a generous estimate for the cost of developing and operating the hardware necessary to obtain the isotope from the surface of the Moon. Even enthusiasts of lunar resource extraction have expressed skepticism about He-3’s usefulness in the past—if the element can drive a full-scale power plant, that’s one thing, but the technology to do that has yet to be developed.

Interlune’s backers argue that increasing the supply of He-3 will incentivize the creation of these systems, but it’s a real chicken and egg problem.

It’s not clear how He-3 is distributed in the lunar regolith, which is why Interlune’s first mission is designed to explore that question. The company hopes to be returning He-3 to Earth by 2030, and then to expand to other lunar resources.

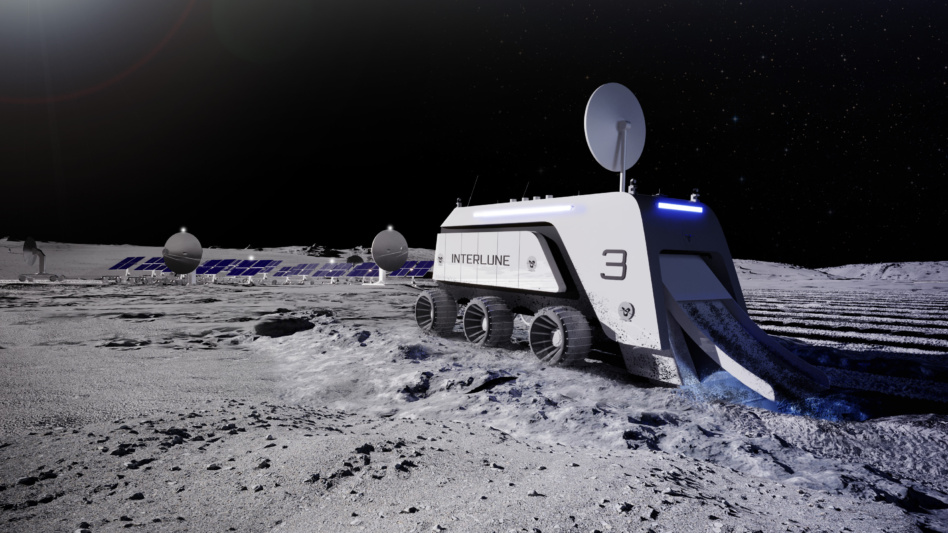

To make an omelet: Just getting at the helium might be tricky. Some lunar scientists expect that obtaining enough He-3 to be useful will require processing many tons of lunar soil, which could prove both politically and operationally challenging, though Interlune said its lunar harvester is smaller and more efficient than other concepts. Once processed on the Moon, Interlune will need to get its He-3 back to Earth, which is itself no easy task.

An important question: Interlune’s existence is made possible by NASA’s CLPS program, which will help subsidize its lunar transit. But the CLPS providers and other lunar businesses are mainly counting on NASA and other government agencies to be the main customers for lunar services or resources like water or its potential derivatives.

The cislunar economy needs more private demand if the billions being sunk into Moon business are ever to deliver a return—and right now, the quixotic hunt for a rare isotope is providing some.