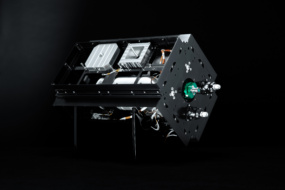

Image: Phase Four

El Segundo-based Phase Four today finalized a lease to build a second factory and scale production of its Maxwell engine product line. The new Hawthorne facility will be over 3X larger than Phase Four’s current plant, and capable of cranking out 100 engines a year.

Phase Four’s founding vision was to create a new type of propulsion for constellation operators, CEO Beau Jarvis told Payload. The company now sees a big opportunity to reinvent propulsion systems and their supply chains by switching to cheaper, easier-to-source fuel.

The pitch

Phase Four is developing electric propulsion systems with four key differentiators:

- Quicker time-to-market/orbit (sub-four month lead times)

- Mass manufacturable (thanks, in part, to miniaturized components)

- Fuel-agnostic (a work in progress)

- Affordability

The technology

Phase Four is developing what it calls the RF Thruster (RF = radiofrequency), which it is adapting to run on unconventional fuel.

- Six of Phase Four’s Maxwell Block 1 engines are already on-orbit and four more are going up this year on commercial spacecraft.

- The startup will integrate its second-gen RF Thruster into Block 2 engines, which should enter production this quarter.

- To be clear, Phase Four’s V1 Maxwell still runs on traditional propellants. But the north star is plasma thrusters powered by new types of fuel. Onboarding advanced propellants is a major R&D initiative underway at Phase Four.

Phase Four’s opportunity

Returning to the topic of affordability, ”most of our customers are building these large constellations of satellites,” Jarvis said, and “can’t afford a million dollar or even half million dollar system.” The unit economics don’t work, he said.

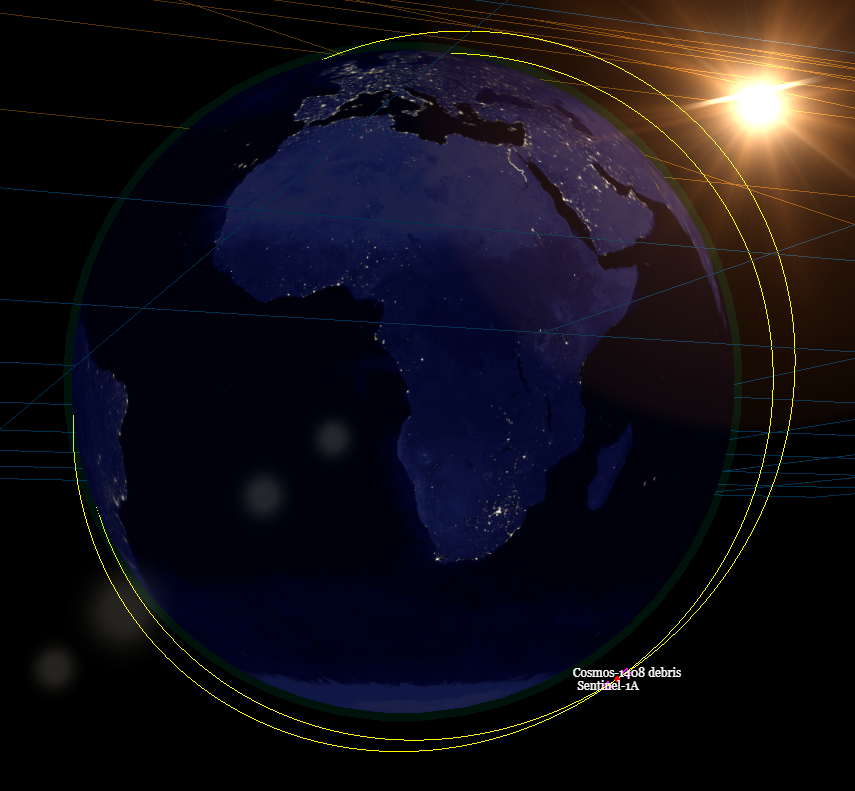

But 80% of the upmass delivered into LEO today is small satellites, Jarvis said. Most of those birds are still running on technology first developed in the Cold War. The technology performs well and if it ain’t broke, don’t fix it, right?

Not quite. Recent events have conspired to throw legacy propulsion’s cost structure out of whack:

- Supply chains are already tight as it is.

- A high share of traditional propellants—purified noble gasses such as xenon and krypton—are produced in Russia and Ukraine. Those sources are now offline.

- “Another large amount comes from China,” Jarvis said, which won’t sell into the US as much anymore “because they have their own space industry they’re developing.”

Sign of the times

Six months ago, a kilogram of xenon would set you back $5,000. “Fast forward to a couple weeks ago, and we got a quote from a local supplier that was over $30,000,” Jarvis said. Seeing the writing on the wall, prime contractors have bought up most of the noble gas supply. “We actually took a bet in February where we bought as much, frankly, as we could afford,” Jarvis said.

What’s next? Phase Four is targeting Q4 for the Hawthorne ribbon-cutting and plans to double headcount by year’s end.

The startup is also currently raising a Series B, and while it may be rough out there in the capital markets, Jarvis isn’t dissuaded. “For companies with working technology, existing customers and demonstrated product demand, there are still solid opportunities to raise in the current market,” he said.