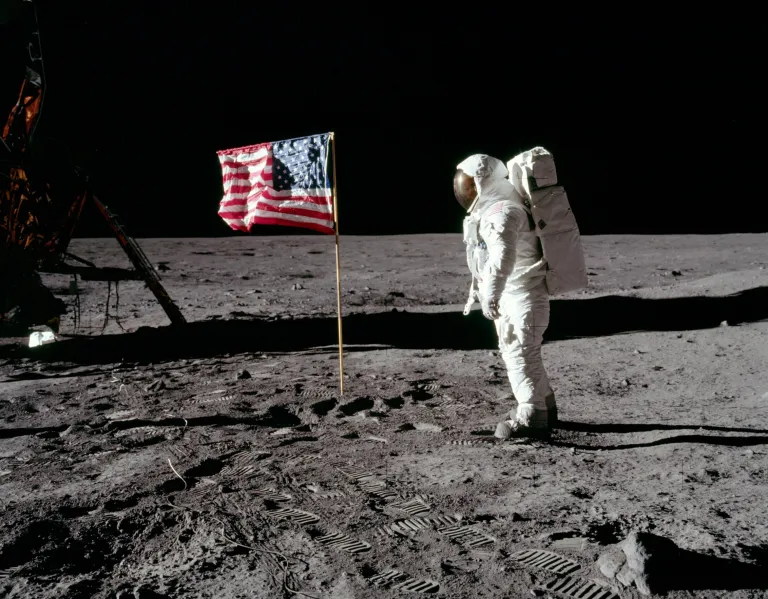

Surrounded by the relics of space exploration, officials met at the National Air and Space Museum’s Steven F. Udvar-Hazy Center last week to discuss how to preserve the history of humankind’s farthest incursions into the cosmos 239,000 miles away.

AIAA’s Outer Space Heritage Summit brought together experts from the historic, policy, legal, and scientific communities to talk about ways to protect important areas in space, including the Apollo Moon landing sites, as commercial activity ramps up.

Rules of the road: There are a couple existing rules to protect the lunar landing sites in the US:

- NASA’s voluntary guidelines issued in 2011 asked space-faring entities to avoid landing within 2 km of the Apollo landers.

- The One Small Step to Protect Human Heritage in Space Act, which became law in 2020, makes the voluntary guideline binding on any entity working with NASA.

However, any comprehensive protection for sites in space has to be international, since federal agencies and commercial actors outside the US are landing on the Moon.

That’s part of why the preservation of space heritage was included in section nine of the Artemis Accords, a non-binding set of guidelines with 42 signatories, according to Mike Gold, a chief growth officer at Redwire who worked as NASA’s associate administrator for space policy and partnerships while the accords were being drafted.

“For the first time, the Artemis Accords put teeth into the Outer Space Treaty. At the very least, if you violate the Accords, you can’t be a part of the Artemis program. There’s a repercussion for the first time,” Gold said.

Preserving the legacy: The hordes of school groups and tourists at the Udvar Hazy museum gawking at the space shuttle or taking pictures with models of space hardware prove that people want to experience space heritage, and the space community seems to agree that it’s important to preserve history in space. One of the biggest questions is how to do so in a way that’s accessible to everyone, even if that means using tech like virtual reality down on Earth.

“You don’t want to be in a situation where the only two people who get to tour the Apollo landing sites are Bezos and Musk,” said Ann Garrison-Darin, a principal professional staffer at Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory.

Any agreements also must overcome the natural tension between historians’ desire to preserve the sites untouched, scientists’ desire to keep parts of the lunar surface pristine for study, and commercial companies’ desire to have unfettered access to the Moon to turn a profit.

What’s next: People didn’t consider this during the Apollo program, but officials at the summit stressed that this has to be part of the conversation about future space missions, especially as the US embarks on crewed or robotic interplanetary flights.