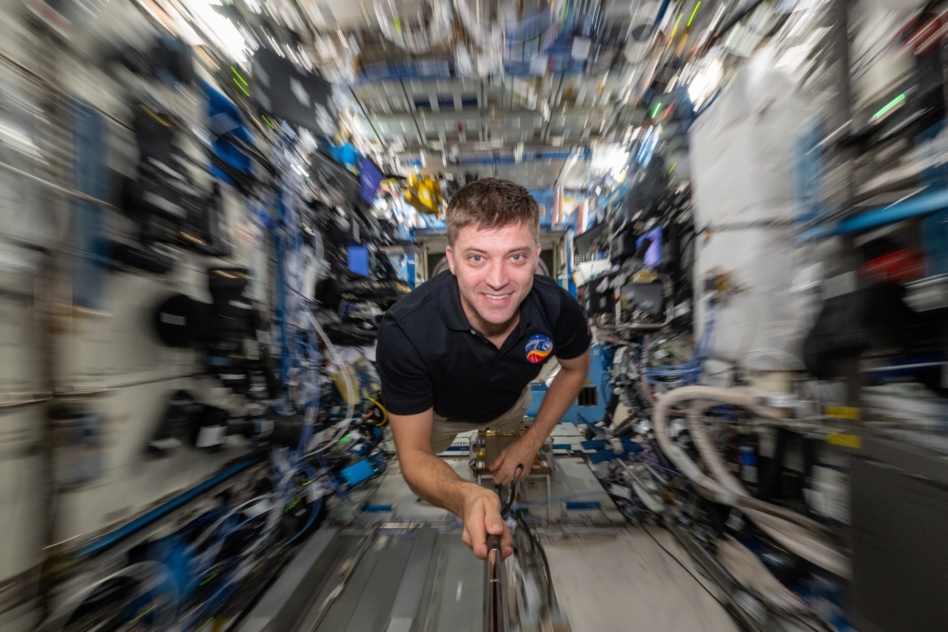

NASA astronaut Matthew Dominick spent nearly eight months aboard the ISS—and he has the photos to prove it, running the gamut from auroras bouncing off the station’s solar panels to technical shots that provide data for Earthbound decision makers.

“You go from art to taking pictures to keep people alive,” he told Payload.

His first trip to the station was a memorable one that involved countless experiments, including one where he was the subject—studying an astronaut’s health after abstaining from the onboard treadmill for the duration of the mission. In his downtime, he also took some photos. A lot of them. By Dominick’s count, the ISS downlink was inundated with 350,000 photos during the mission.

At Payload, we’ve been huge fans of Dominick’s photography. We chatted with him after he spent a few months Earthside about his time on the ISS, and his feelings behind some of the photos he captured.

Questions and answers have been edited for length and clarity.

First off, how does it feel to walk again after so long?

I didn’t walk for eight months because I was in a special program where I didn’t use the treadmill. The last time I walked was walking over to the spaceship and getting on board. So it’s pretty awesome.

The worst part is sitting. Sitting is awful. If you haven’t sat in eight months, the way your backside works, I guess it builds up some kind of resiliency to sitting in a chair. The first couple weeks I was back, it was just too painful, and then all these research experiments want you to sit on a bike and pedal, and you can’t sit on a bike seat. Jeez, it’s the worst. I’d come home and have dinner with my family and I would just lay on the floor and say “Guys, I can’t sit.”

Well, it looks like you’re back up at it now…Down to the photography. I’d love to know a little bit about the training process before you went up to station, and what were some of the unexpected lessons that you learned the hard way?

NASA provides a formal training syllabus whereby you practice. They teach you camera fundamentals, how to use the software on the particular camera models we use, and they do a good job. They’re great instructors, but a lot of it, like many things, is up to you what kind of homework you do.

I would take a camera home and I would practice. I have kids, and so I would take pictures of my kids’ sporting events. I was taking pictures inside a dimly lit gym, and it turned out to be somewhat applicable because of the orbital speeds that we’re moving at. I remember taking a picture of this hurricane, and we have radiation problems on the space station, so the camera I was using froze up. It wasn’t working, and the lens I was using was the only one we had available for that particular shot. So, bam, bam. I switched it out, swapped the lenses, grabbed the other camera, put it on, reset, got it to the settings I wanted, took a picture in time.

You’re moving at 17,500 miles an hour, so you’re going to blow through a shot in 15-30 seconds. Having practiced doing that on Earth so many times, the camera was like just a physical extension of my body. I could do that camera swap without thinking, having done it in sporting events for my kids. It’s oddly applicable.

There’s such a small group of people who’ve been to space, and then even smaller that show the level of interest in photography that you and your mentor Don Pettit show. What were some of the things that he taught you?

He taught me a lot of things. He’s my mentor in the office, so I was at his house a fair bit prior to launch, but the big thing he taught me was to check out a camera and practice. You need to make mistakes on Earth. You need to have an intuition for aperture, shutter speed, ISO, etc, before you launch, so that you don’t have to think about those things on orbit.

In looking at your portfolio compared to Don’s, there are some different stylistic choices that you guys make. In this nascent field of astrophotography, how would you describe your style versus Don’s?

You’re not the first person to mention that I have a style compared to Don, but I think we agree on some things and we have tastes for others. One of the things I think he and I tend to prefer is taking images that show that we are on a space station. You can take a picture of the Earth that just shows the classic straight down. Is this a spy satellite image, or is this taken from Space Station? Don and I both prefer to have pieces of Space Station structure framing the shot because, man, I just think that’s really cool.

The other one is seeing the horizon. I really like pictures that show the horizon of the Earth. Most of your weather satellites are all kind of straight down focused on weather, and you don’t get that beautiful horizon shot that we get to see with our eyes. And so, I wanted to capture what we see and share that with the world from the perspective of the person who’s in space.

One of my favorite pictures I took was one of aurora from out of the Dragon, right as the world is coming by. It shows the window frame of the Dragon. I had a little light in the background dimly illuminating the window frame without creating a reflection, just to show, hey, there’s a human being looking out this window, looking at Earth. So Don and I agree on that.

I think he tends to lean more towards nighttime city photography, and Don has been crushing that. Don has spent a lot of time on the technique because you can’t just point and shoot, otherwise you’ll get streaking. So, he’s actually tracking the city to remove orbital motion with his eye and firing off the shot. He’s absolutely crushed that photography, and that’s something that I would probably dive into later.

A lot of people who get back from space say that pictures don’t capture it. What does the camera miss that the eye captures?

Cameras do not have the dynamic range of the human eye. We would make a time lapse, but it would be a day time lapse or a night time lapse.

I remember having a conversation with my crewmate Loral [O’Hara] about just how beautiful the solar rays are in that transition. The golds and the blues in the Russian segment, and how the rising sun is reflecting light through the atmosphere, bouncing off the solar rays and into your eyes. It’s just incredible and I couldn’t get the camera to capture it because it’s moving too quickly in the dynamic range, it’s too much for the camera to handle. Don and I talked at length about capturing it and we’ve not done it yet.

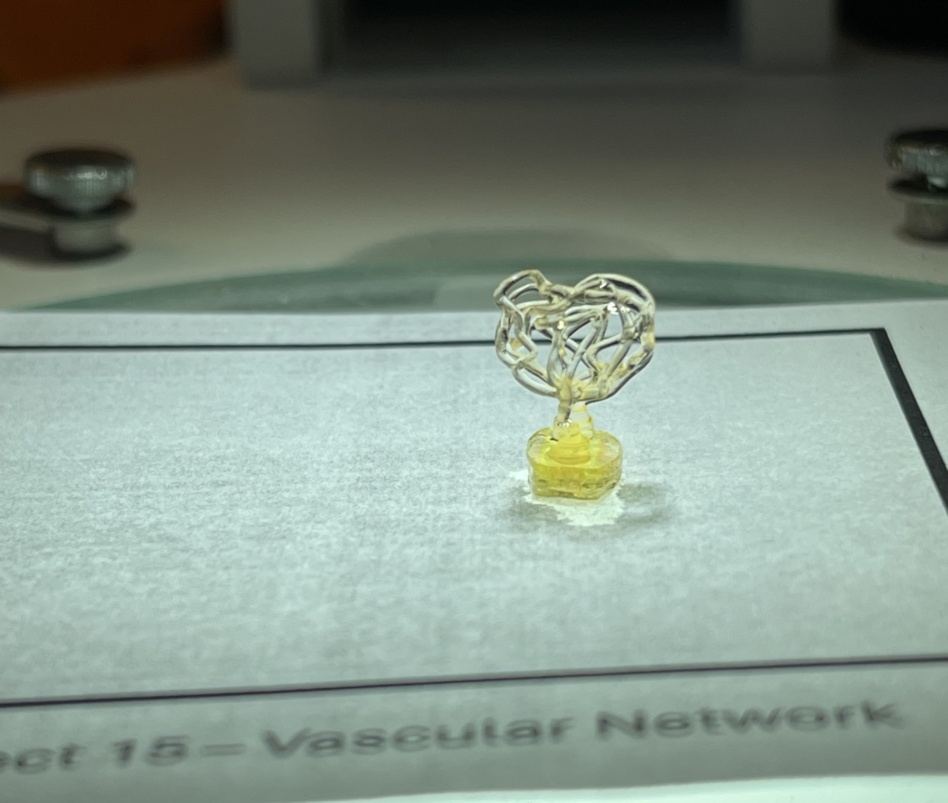

Obviously, a huge reason that NASA sends up cameras and prepares you is because you take photos and videos of experiments on Space Station.

The photography NASA trains us to take is technical in nature. A lot of what I did was taking pictures for artistic purposes, but the photography they asked us to take is technical. When you’re taking a picture of an experiment, you have an obligation to deliver that scientist the best image possible, so they can do their research and see what’s going on. Anytime I picked up a camera to take a picture of an experiment, I carried with that a responsibility to deliver the best pictures possible.

From an engineering side, the engineering team was trying to make decisions about how we proceed with the next spacewalk, and there was what we thought might be damage on one of our space suits. It was really tough lighting. I probably spent an hour and a half taking hundreds of pictures trying to get the right one or two that would show them what is going on mechanically with the spacesuit, so we could make a decision to send a human being outside. A bad picture might drive the wrong decision. You’re taking pictures that the lives of future crew members will depend on, so you go from art to taking pictures to keep people alive. It’s a super huge spectrum.