This is the third installment of our deep dive on orbital debris. Read Part One and Part Two.

–

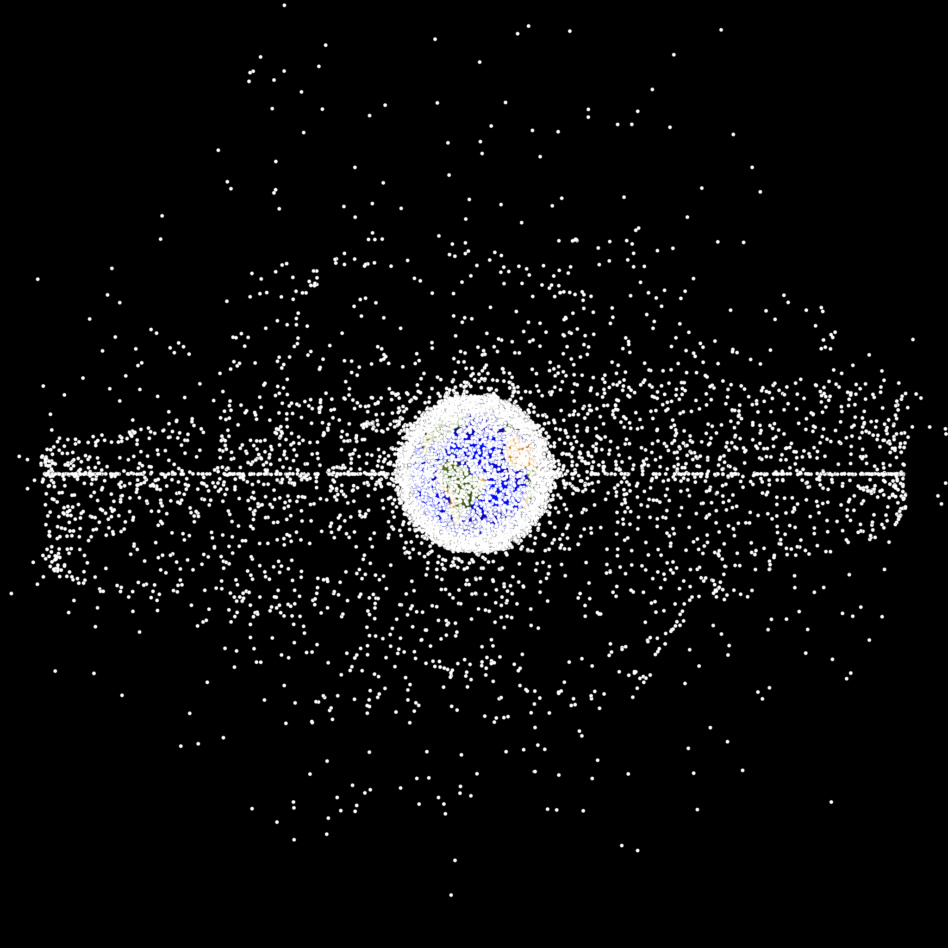

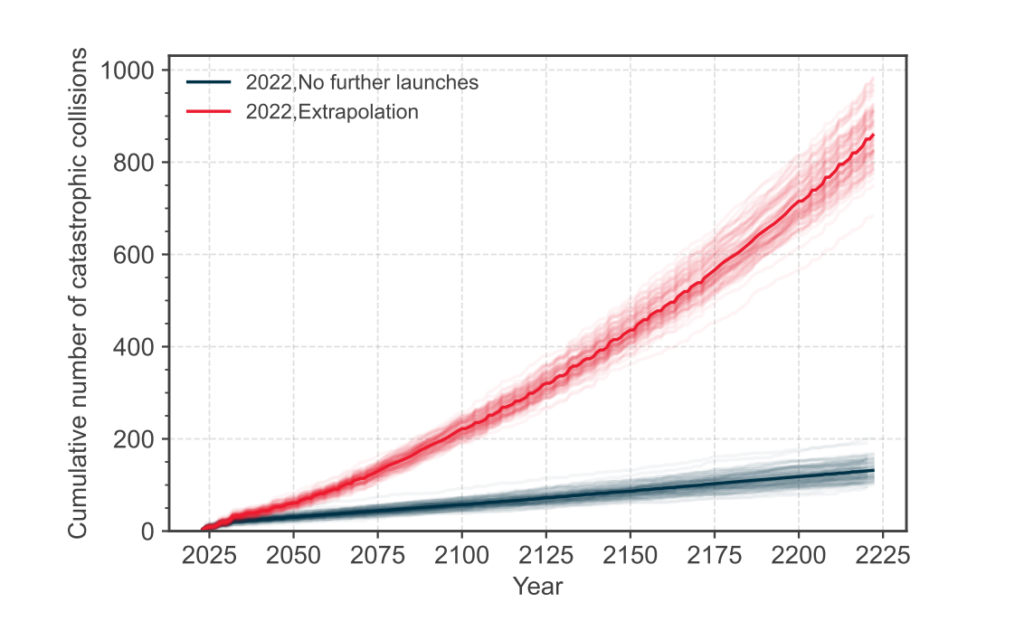

Space is getting more crowded, especially in the regions where satellite operators vie for the best orbits. The density of operational satellites is increasing faster each year. And as for the debris already up there? It’s not going anywhere for a while.

We may not have the ability to proverbially sweep up in orbit, but we do have the power of foresight. At humanity’s disposal are technologies that military, civil, and commercial operators have actively tapped for decades to track threats, predict potential collisions, and when applicable, steer around them.

Still, hurdles exist.

Tracking orbital objects is difficult and imperfect. Moreover, getting satellite operators to agree on standards and reliably share information about when and how they’re maneuvering is no small task. Various public and private organizations are working to improve our awareness in space and ensure that Earth orbit is open for business for decades to come.

Keep your wits about you

Two technologies that help satellite operators avoid in-orbit collisions are likely already on Payload readers’ radar. Space situational awareness (SSA) and space traffic management (STM) can make the orbital environment safer by helping to ensure we don’t create excess debris in the first place. What gets measured gets managed.

SSA refers to the tracking of debris objects and active satellites in orbit. Right now, most orbital tracking information comes from ground-based telescope tracking, such as the DoD’s Space Surveillance Network, which is controlled by the US Space Command’s (USSPACECOM) 18th Space Defense Squadron (or just “the 18th” for short). Some satellites are also equipped with GPS. This works in space, so long as a given satellite is located below mid Earth orbit (MEO), where the GPS constellation lives.

STM, on the other hand, refers to technology that predicts when and where collisions could occur. It may or may not recommend actions to avoid collisions and keep assets on orbit where they should be.

In tandem, SSA and STM can prevent collisions, which can stop the creation of space debris in the first place. Simple in theory, but less so in practice.

Why bother with awareness?

Companies currently operating in orbit employ STM services to protect their on-orbit assets. NASA, the 18th, and commercial space players publish or otherwise provide SSA data to help satellite operators keep better track of what all is floating around up there. These technologies are more advanced than on-orbit debris mitigation measures, and they have more functional business models underpinning them.

“One of the things that is really missing at the moment is being able to share data [and] information,” said Luisa Buinhas, cofounder of Vyoma, a startup focused on creating an actionable STM platform to help companies minimize and automate maneuvering operations. “What you’re witnessing right now is that it takes a long time from the moment that you realize that you have a conjunction coming up to the point where you actually decide to act on it.”

A conjunction, while we’re here, is when two objects in space pass near each other. When those two objects are active satellites, the owner-operators on both ends need to talk to one another and coordinate. That can involve making a determination of whether a maneuver is necessary, and if so, who will get out of the way.

Slingshot Aerospace, another startup, is building an STM platform called Beacon, which is focused on making that communication easier, particularly between the military and commercial segments of space.

“We have to have a common platform so that satellite owner-operators can not only communicate, collaborate, and coordinate on deconflicting risks…but we have to do that in real time with a scalable infrastructure,” said Slingshot CEO Melanie Stricklan. “However, operators receive conjunction alerts often, and they are often false alarms or close approaches that don’t actually need maneuvers. That racks up a bill.”

There’s demand for services that help companies better overcome these challenges, Buinhas said, and companies are willing to pay for that information.

For every false alarm, Buinhas said, “satellites will spend more time maneuvering out of the way instead of operating. And companies cannot afford to have satellites up there if they’re not actually generating revenue.” So it makes economic sense that STM as a service (STMaaS…?) is in demand right here and right now. Active debris removal, or ADR, on the other hand, is not.

A big data problem

“The truth about sensors is that they all lie,” Moriba Jah, cofounder of SSA startup Privateer, told Payload last year. “There is no true sensor. All sensors lie; each one has some bias. The best way to know that you have an accurate clock is to have hundreds of them. We need to solve the big data problem.”

Ground-based observation currently provides the vast majority of data we have about where satellites are at any given moment. But while a satellite is out of view of any ground sensor, operators need to estimate its location by modeling its most likely trajectory.

“The reality is that we don’t know precisely where an object is in orbit,” Araz Feyzi, CTO of STM company Kayhan Space, told Payload. “It’s in a bubble of uncertainty, or a cone of uncertainty.”

Why, you might ask, can’t we tell precisely where a satellite is based on the data we do have about where it’s been and where it was headed?

“The Earth is not round. Gravity is not constant,” Andrew D’Uva, president of Providence Access Company, an advisory firm in satellite solutions, told Payload. “There are multiple forces in space…that are perturbing orbits, so things don’t just continue to orbit the Earth in a very predictable way. Predicting those orbits, depending on many, many factors, actually requires a lot of force.”

A shortage of adequate data isn’t the only issue in reliably monitoring satellite positions. There’s also the question of how to route it to the right people in a usable and timely fashion.

“These different systems that the operators use [are] spitting out information, and although they have authoritative data, that information is in different formats,” said D’Uva. “When you’re trying to compare information…If you’re not speaking the exact same language, the comparisons don’t make any sense.”

The 18th currently tracks objects in orbit (both dead and alive), and works with commercial operators to coordinate maneuvers as needed. However, Feyzi said, that work isn’t really the 18th’s mandate. Since they’re the only entity with the ability to evaluate potential maneuvers, they’ve fallen into the role.

Many commercial companies—including Kayhan, Slingshot, Vyoma, and Privateer—are working on ways to consolidate more satellite position data and make it easier for operators to pick maneuvers. Still, the consensus is that more frequent, higher-quality data is needed for these systems to be as effective as they need to be.

“Just as it’s not really tenable for a spacecraft operator to be an island—they need to work with the other ones—it’s now untenable also for SSA systems…to think that they’re an island,” said Daniel Oltrogge, chief scientist at SSA company COMSPOC and director of the organization’s center for space standards and innovation.

“They’ll come up with their catalog based on their historical observations. But without pulling in the observations from the spacecraft operators, and their ephemeris and their maneuver plans, you still aren’t going to close the loop.”

To regulate, or not to regulate…

Right now, American satellite operators are not required to report maneuvers. Each company individually reviews conjunction notifications and makes the ultimate call on when—and whether—to maneuver. Then, the company has the option to report this information to USSPACECOM so it can update its model of where everything is in space. Many companies do, but many do not.

Not everyone wants extra regulations—shocker—on how and when they have to move their satellites. Or, for that matter, marching orders to report those moves.

A possible alternative to strict regulation? Encouraging operators to collaborate on acceptable rules of the road in space, and voluntarily adhere to a set of mutually agreed-upon standards. After all, no one wants an unexpected collision to come for their multi-million dollar satellite.

“You want those standards to evolve naturally out of experience and practice,” said D’Uva. “When you turn around and try to make them regulations, you get sharp division, because in some cases those regulations will benefit one technology or one group over another. And so you get pushed back. Space really is developing very rapidly. And regulatory agencies take time to do things.”

The UN maintains a set of space debris guidelines which encourage the sharing of data. The US has also taken steps to set the tone for creating standards for traffic management in orbit. In July, the White House released a national orbital debris implementation plan, which encouraged satellite operators to increase the amount of data they share publicly about their satellites. The plan, among other things, includes revisiting the current 25-year post-mission deorbit guideline. That tenet is close to fruition, as the FCC last week released a draft rule that would require operators to deorbit after five years.

The future of maneuverability

Right now, when an operator gets a conjunction notification that requires a maneuver, a human needs to go through a lot of manual steps in order to move that satellite out of the way. Someone needs to look at that satellite’s orbit projections and perform analysis to decide what maneuvers they can make, then check whether those potential maneuvers will put the satellite on a collision course with something else, and iterate from there.

But as more and more satellites are launched to orbit—tens of thousands over the next decade—this manual process isn’t going to cut it anymore.

Already, the lead time for warnings is shrinking. Europe maneuvered Sentinel 1A in May, hurrying the SAR spacecraft out of the way of a leftover piece of debris from a Russian ASAT test last November. ESA said it had less than 24 hours’ warning. Events like this are likely to become more and more common, as key Earth orbits get more and more dense with operational satellites.

Feyzi believes that someday soon, all satellite maneuvers could be fully automated. Kayhan Space’s STM platform, Pathfinder, pulls in data from publicly available sources as well as satellite position, maneuver, and trajectory data from its customers. It then uses that data to automatically generate maneuver options and deconflict potential collisions.

Right now, a human is still in the loop to pick the maneuver best suited for the mission. But someday that may not be the case. With potentially tens of thousands of satellites in LEO in the coming years, automated maneuvers and timely reporting will be needed to prevent a tragedy of the commons, per Feyzi.

Before we develop a dense environment in LEO that leaves little to no room for error in collision avoidance maneuvering, we need the infrastructure, oversight, and collaboration it will take to manage that traffic.