Mining in orbit is getting closer to becoming a reality and, with business prospects protected by policy—at least in the US—one investor is predicting the dollars will start rolling in.

“My hot take is that there are too many investors sleeping on space tech because they are too risk averse,” said Katelin Holloway, a founding partner at 776 venture capital firm, which invested in both Astroforge and Interlune. “In order for this to work for you, you have to be confident enough to make a big bet. You have to be willing to trust that the rules and regulations will follow.”

“Whenever success enters the chat, the regulators show up in droves,” she continued. “This is how you know when something is about to take off.”

Show me the money: Space mining is still a tricky business that’s capital intensive, requires sophisticated tech, and offers a longer-term return on investment for investors. But now that some of the big question marks are settled and it’s not “the wild west,” Holloway predicted more money will flow into the sector.

“All of those folks that were super risk averse are starting to feel a little more confident,” she said. “I think these policies will attract a ton of new investors.”

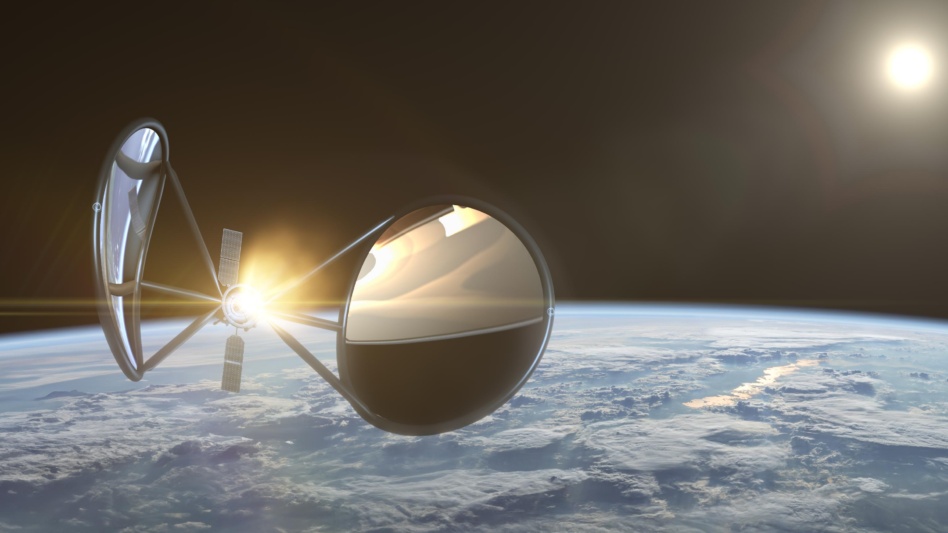

Primary texts: The Commercial Space Launch Competitiveness Act of 2015 is clear: American companies can extract resources from asteroids and sell them. That’s good enough for Matt Gialich, CEO of AstroForge, which is working toward mining platinum from an asteroid.

“Am I allowed to go to an asteroid and mine for whatever I want and then sell it here on Earth? The answer to that is 100% yes,” he told Payload.

Moonward bound: The 2015 law that explicitly okays asteroid mining doesn’t make any explicit mention of the Moon, but does allow an American to collect and sell a “space resource,” defined as any “abiotic resource in situ in outer space” (so no selling aliens).

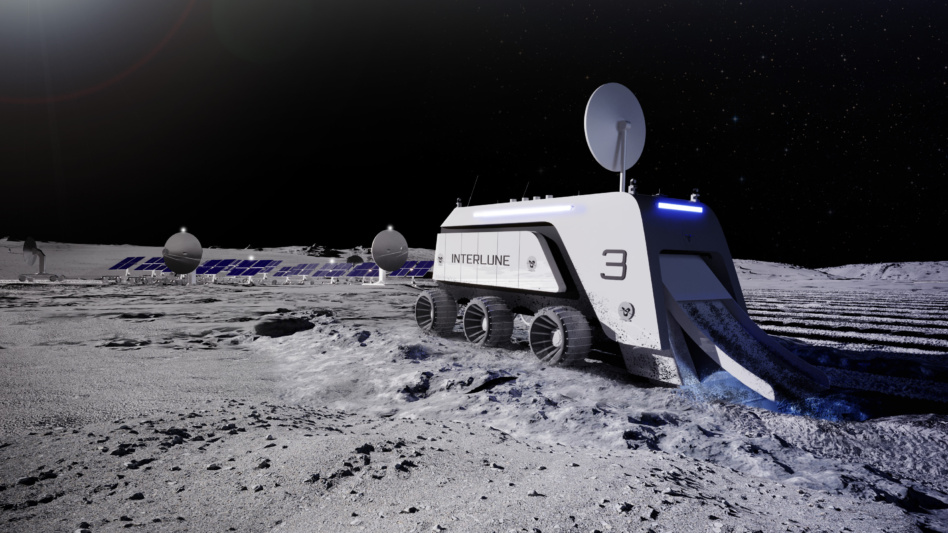

Rob Meyerson, the cofounder of Interune, a startup aiming to harvest He-3 from the lunar surface, said Moon mining is covered by the law, and that NASA awarding contracts to companies to return lunar regolith back to Earth and sell it to the agency is proof.

“Not only is the law there, but NASA has stepped up and said we believe in the law in a way that we’re going to step up and award these contracts,” Meyerson told Payload. “Nobody has acted on that yet, but I think we’re very close.”

DC footprint: AstroForge does have some staff in DC, but said conversations with the government are not a top priority. “Let us go prove we can do it and then I’ll have enough money to go hire all of DC and we can go lobby the government…but because we have this law that says right now that we can do it, it’s not something we’re super focused on.”

Interlune has no DC presence—all 12 people at the new company are based in Seattle—but Meyerson said he made his first Hill visit last month to get lawmakers up to speed on his tech.

“We just had three meetings…Just to introduce them to the idea and why it’s important. I think it’s so important to have a dialogue with them,” Meyerson said. “There are a lot of different perspectives on mining the Moon.”

Overseas questions: The legal situation surrounding space mining gets a bit murkier when you look outside the US, according to Michelle Hanlon, executive director of the Center for Air and Space Law at the University of Mississippi School of Law. The nearly 40 nations who have signed on to the Artemis Accords agree with the US position, but other countries could take a different position.

“I think it’s going to be an argument about whether something is for a commercial use or a scientific use, that’s where we’ll get caught up in the international community,” she said.

Gialich said he believes international action on space mining akin to the regulations imposed on terrestrial mines will only come after a company successfully harvests and sells material collected in orbit.

“People will want to regulate, people will want to break up monopolies, this is how the world works,” he said. “Regulation will come upon our success, and we have a little bit of a job to do to make sure we’re ahead of that and part of those conversations, but at the end of the day, I’m really focused on the success part.”