TOKYO—Koichi Wakata could barely move around the conference floor without being mobbed by fans for autographs and selfies at Spacetide, an Asia-Pacific commercial space conference.

Wakata made his name during five trips to orbit as an astronaut representing the Japanese government. Now, he’s using that fame to help usher in a new era in the Japanese space world driven by the private sector as Axiom Space’s CTO for the Asia-Pacific region.

“I would like to leverage my experience to promote further private sector opportunities,” he told the crowd during a discussion of the industry in Japan at the conference.

Wakata’s transition is emblematic of a broader shift in Japan’s space industry as it seeks to become one of the world’s major private space markets.

A big decade

“I still see reporting sometimes, [of] ‘Where are the hotspots of commercial space globally?’ And I don’t often see Japan listed,” said Chris Blackerby, the COO of Astroscale, the publicly-traded Japanese space sustainability firm. Unsurprisingly, he disagrees. “There’s this vibrant space community here, and people are starting to recognize that.”

Blackerby came to Japan in 2012 as NASA’s attaché, focused on JAXA’s wide-ranging collaborations with the US space agency. At the time, the main space businesses were Japanese industrial giants like NEC, IHI, MELCO, and MHI, akin to the US primes. But by 2017, he had been convinced to join Astroscale by founder Nobu Okada, who had realized the challenge—and business opportunity—in orbital debris before many of his current competitors.

“Japan, I think, historically, hasn’t been known as a place where there’s a lot of startup mindset,” Blackerby noted, adding with a laugh that “when I told my [Japanese] mother-in-law that I was going to this start-up company…she was not happy.”

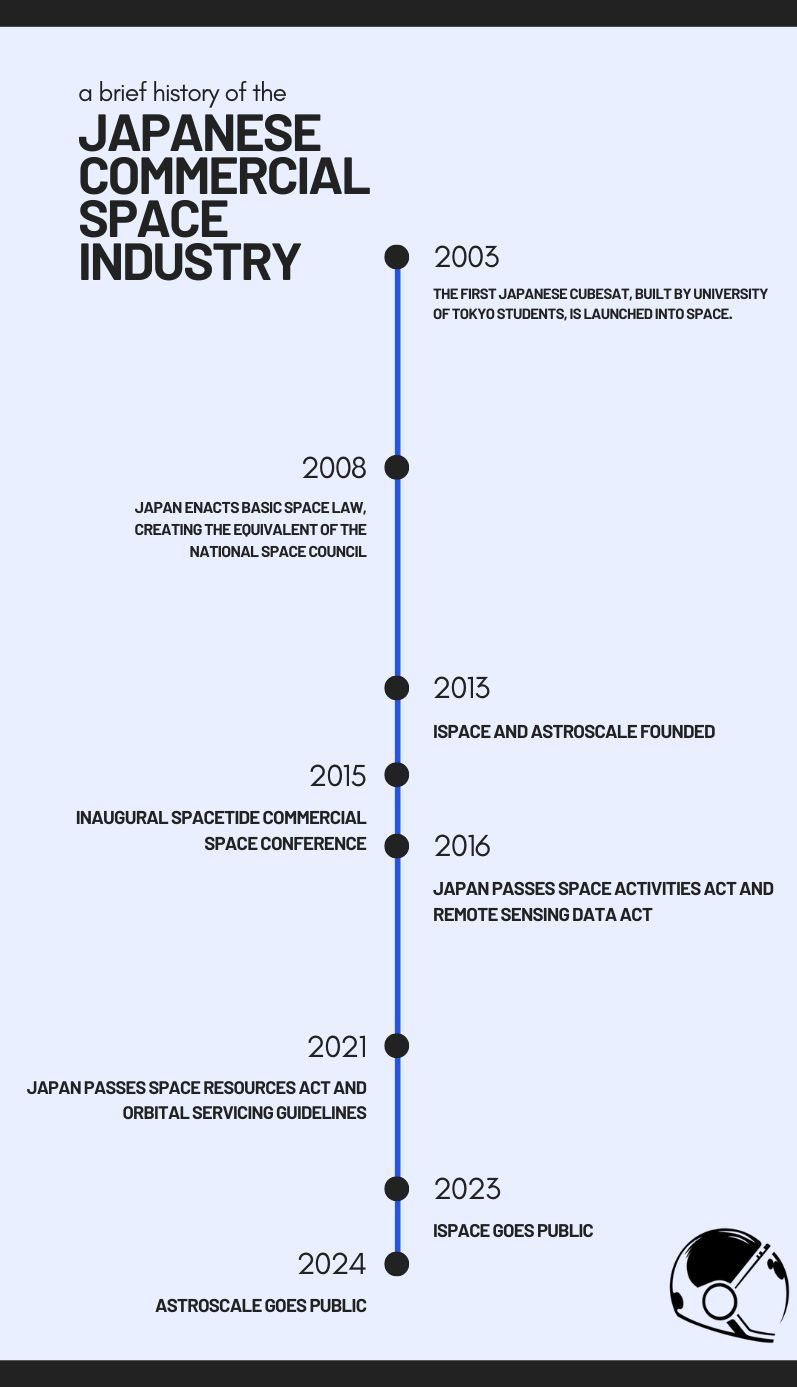

That’s changing—when Blackerby joined Astroscale, there were only a handful of space start-ups. Three of those early movers—Astroscale, ispace, and iQPS—have since gone public. And there are more than 100 new space firms in the country, according to Masayasu Ishida, who founded the Spacetide conference in 2015 to bolster the industry.

“I feel the power of the APAC region here,” he told Payload. “Historically, the US and Europe have been leading the space industry, but the global space sector is undergoing a major transformation—commercial space will be the driving force over the next 10 years or 20 years. In this new era, I believe APAC leads the next growth phase for the global space industry.”

Entering global markets

While Japan is an economic powerhouse, its demand for space services is still on the smaller side compared to the US, EU, or China. That means companies there need to be thoughtful about what they’re developing and, advocates say, take their wares abroad. That also influences the business models companies there pursue.

“We have all these great technologies from Japan, but we’re not selling it overseas,” said Shinichi Nakasuka, a University of Tokyo aerospace professor. “If we are only looking at the Japan market, the market’s too small. Japan’s terrestrial network is so well developed, there hasn’t been too much investment in developing a satellite constellation.”

Astroscale, probably the world’s leading space sustainability firm, boasts five global offices for this reason. Founder Okada summarized the challenge: “Most of the startups in Japan are looking at the Japanese market first, but it’s tiny, not enough to become profitable. So then they need to go to the global market, but that means big capex, right?”

That also means that Japanese start-ups need to turn abroad for funding, or look to public markets sooner than their compatriots abroad. Takeshi Hakamada, the CEO and founder of ispace, which will make its second attempt to land on the Moon later this year, raised a more than $90M Series A in 2017—an impressive accomplishment but one he considers “the maximum” in Japan’s VC market. That’s one reason his company sought to tap public markets in 2023.

People problems

One issue has the Japanese industry fretting most: Workforce development. Okada estimated that Japanese universities produce just 50 space engineering graduates each year, which is another reason he has so many offices abroad—talent acquisition.

“No matter how much funding the government allocates, if we don’t have the right people, we aren’t going to win,” said Jun Kazeki, Japan’s top space official, who prioritizes finding talent from outside the space industry.

The shortage is not just in space, but also AI and big data, Ishida said. And beyond engineering, there is also the need for traditional corporate functions like sales, marketing, and branding. He hopes to see the creation of a space MBA to introduce business-minded students to the space sector’s particular challenges.

Hakamada, the ispace founder, has another kind of business education in mind. He’s familiar with a particular trap that comes with hiring space engineers, who want to build the coolest fully-featured technology without always thinking about the business implications. But he also knows that the space sector needs outside of the box thinking.

“They are afraid to fail,” Hakamada told Payload of traditional space companies. “Failure is important for success. If you have been in the industry ten or twenty years, the only idea is the obsolete or the never tried—a fresh mindset can come to the industry and try, some of them may succeed.”

Learning from the US…

Japan has looked to the American example of public-private collaboration as the next step forward in developing the space industry, including the launch of a $6.2B fund to back private space R&D over the next decade and the doubling of the government’s space budget in the last three years.

“The US commercial space ecosystem has grown through tight coordination with government customers as well as a shift in US government policies toward supporting space companies,” NASA chief economist Alexander MacDonald said in Tokyo, telling Payload that Japan’s swing was similar to the policies that helped Luxembourg punch above its weight in orbit.

“By having access to the government’s wallet, the private sector can grow,” Nakasuka said.

As in the US, geopolitics drives this government interest, with Japan warily eying China’s space capabilities, particularly around long-range missiles.

“The US Space Force is now aiming to build a hybrid architecture which integrates commercial space solutions,” said Fukushima Yasuhito, a researcher at the Japan National Institute for Defense Studies. “And also Japan is actually now supporting the development of commercial space technologies with high dual use capabilities, and also trying to expand its use of commercial subsidy [for] defense purposes.”

…With a Japanese flavor

“The Japanese startup scene is kind of embryonic, but…the quality of the startup is amazing,” said Peter Beck, CEO of the US-New Zealand launcher Rocket Lab, which has multiple customers in Japan. “The hardware is wonderful of course, as you’d expect, but, you know, the businesses and areas they’re going after [are] excellent. Let’s say a couple of years ago, you could swagger down Silicon Valley with SpaceX on your CV and raise money to do something nuts—whereas that just doesn’t occur in Japan.”

Ishida cited the participation of non-space companies as a unique advantage of Japan’s space sector. Strategic investment from large corporations is a major factor for the country’s space start-ups, in part because, as Beck noted, large amounts of local VC funding are hard to raise.

Mitsubishi UFJ, one of Japan’s—and the world’s—largest banks, has financed plans by Sierra Space, a US space firm, to develop a spaceport in Oita, Japan, which had once been intended as a potential operating site for Virgin Galactic. Now, it may see Sierra’s Dream Chaser spacecraft return from orbit to land there.

Seiichiro Akita, a senior executive at MUFJ, said his firm was most excited about the spill-over effects into the non-space market.

“It’s not all about space hardware anymore,” Akita said, arguing the rising importance of downstream applications for space technology, like data, communications, and PNT, will herald new growth for the sector, forecasting that it may outstrip the semiconductor industry in revenue by 2030.