Few NASA projects have received as much high-profile criticism as the plan to put a space station called Gateway in orbit around the Moon.

Space notables—moonwalker Buzz Aldrin, former NASA administrator Michael Griffin, Mars advocate Robert Zubrin, and planetary scientist Clive Neal—have all opined that the project is a waste of time, the wrong architecture, or a distraction from real priorities.

So it’s no surprise that President Donald Trump’s top-line budget called for the cancellation of Gateway—or that, while it’s still full steam ahead at NASA and the program’s contractors, the Hill staffers, space advocates, and former NASA officials Payload spoke to don’t expect the station to be saved in its current form. Jared Isaacman, Trump’s nominee for NASA administrator, wouldn’t commit to more than taking a hard look at the program at his nomination hearing.

And yet, after years of work, the core hardware for Gateway is being integrated and tested for a planned launch in 2027. Could it be repurposed? And is there a method to Gateway’s madness after all?

Lunar pied-à-terre: Gateway emerged, as these things often do, in an attempt to Band-Aid the capabilities required for a lunar return to go beyond a repeat of Apollo’s flags and footprints.

In 2017, then-NASA administrator Jim Bridenstine was charged with finding a way to build a long-term presence on the Moon—while still depending on the expensive and expendable SLS rocket and Orion space capsule, already in progress with prominent backers on Capitol Hill.

“So the question then becomes, ‘Can we create a reusable architecture between the Earth and the Moon?’” Bridenstine asked in a 2018 interview. “Gateway is not the ISS around the Moon. That’s not what it is. It’s a reusable command module so that we can build resiliency into the architecture between the Earth and the Moon. Sustainability is the key.”

Gateway would orbit the Moon in a unique non-rectilinear halo orbit, providing a stopping point where astronauts could spend time in lunar orbit and catch a reusable lander ride to the surface. The station could act as a comms relay for autonomous landers, a testbed for deep space technology development, and a refuge for space travelers in case of emergency.

However, the existing need for a separate lander to transition from Orion to the lunar surface raised a question: Why couldn’t astronauts travel from their spacecraft to the lander without an intermediate step?

In 2020, NASA decided to launch the two main elements of the Gateway on a single rocket, leading to a costly redesign and delaying the project. As the agency pushed to meet the initial (and ridiculous) goal of landing crew on the Moon by 2024, the Gateway was taken off the Artemis “critical path” and thrown into limbo, to be launched after the first planned Moon landing.

Behind the scenes: One engineer working on the Gateway program described it as a “mix of old NASA thinking, new NASA thinking, and SLS shortcomings.”

Gateway’s role in Artemis was never quite clear from a technical perspective, but it offered other benefits that have historically given NASA programs long term staying power. Bridenstine had key requirements: It had to be bipartisan, international, and commercial.

“That’s what the Gateway provides. It provides an on-ramp for commercial partners, for international partners. It enables the US to do more as well—[it will be there] for 15 years,” Bridenstine said in 2018. “You go back to Apollo—we did six [landing] missions—that’s not what we’re doing.”

Numerous space agencies joined the program, exchanging work on the Gateway for astronaut participation in future Moon missions:

- ESA and Thales Alenia Space would provide the habitat structure, and a communications and refueling module;

- JAXA would provide cargo resupply and batteries;

- CSA and MDA would build the new, robotic Canadarm3.

- The UAE’s Mohammed bin Rashid Space Centre would build an airlock module for EVAs.

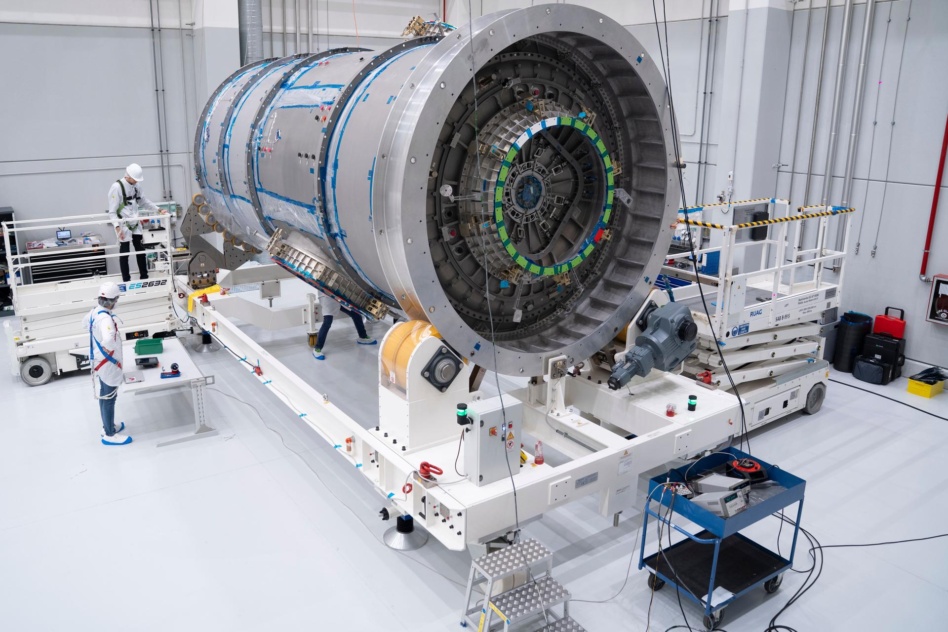

In the US, Northrop Grumman won a contract to integrate the Habitat and Logistics Outpost (HALO) and Maxar to build the power and propulsion element (PPE).

The idea was to secure not just technological contributions from international partners, but political support in the long term.

“The reason the ISS exists today is because of all the international collaboration,” Bridenstine said ahead of the Artemis 1 launch in 2022, noting that lobbying by NASA’s international partners helped save the space station project that ultimately became ISS from an early demise.

Destination station: Besides politics, there’s also a practical reason to have a habitat in lunar orbit: You can go there.

“Gateway builds that political and programmatic inertia to get you used to launching things to the Moon every year for perpetuity.” Casey Dreier, the Planetary Society’s chief of space policy, said in 2022.

Perhaps the ISS’ most important contribution to the space economy was incentivizing the NASA commercial cargo and crew programs that gave the world SpaceX, the Falcon 9 and Dragon. A place to go in lunar orbit, for science and economic missions, could have the same effect.

Second life: The Trump administration’s planned pivot away from the SLS and Orion after the Artemis III mission, expected to launch in 2027 if all remains on schedule, likely hinges on commercial entities that could have been bolstered by Gateway picking up the reins.

The calculus might be expressed as a bet that lower-cost and faster-moving companies don’t need the funding levels required for government-led programs that have bipartisan and international backing. (N.B.: Check back on that in a few years.)

But if Gateway’s cancellation seems inevitable, well over a billion dollars of hardware has been delivered and is undergoing integration and testing—the Maxar PPE and Northrop’s HALO. Could they be repurposed? (MDA is still building Canadarm3, and hopes that if it isn’t in lunar space, it will be deployed elsewhere—perhaps on a commercial station.)

The technology behind the PPE was originally developed for the Obama administration’s poorly-received Asteroid Redirect Mission. It could, in theory, be used for crewed or uncrewed missions to other deep space destinations—including the Lagrange points.

Rumors abound that SpaceX, which is a participant in a Gateway resupply contract with a $7B ceiling, wants to keep that award and repurpose the station for Mars. While Gateway is designed for deep space, its propulsion system is intended for lunar activities and it would require a significant boost to make it to Mars.

Absent SpaceX or another deep-pocketed private sector partner swooping in to retrofit the equipment for the Red Planet or another destination, Gateway will spend its remaining days on its least exciting mission—storage.