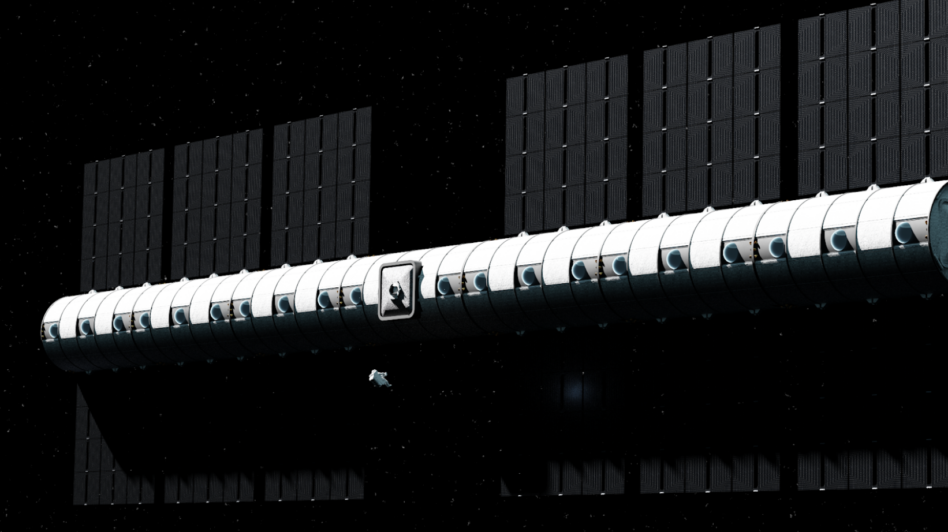

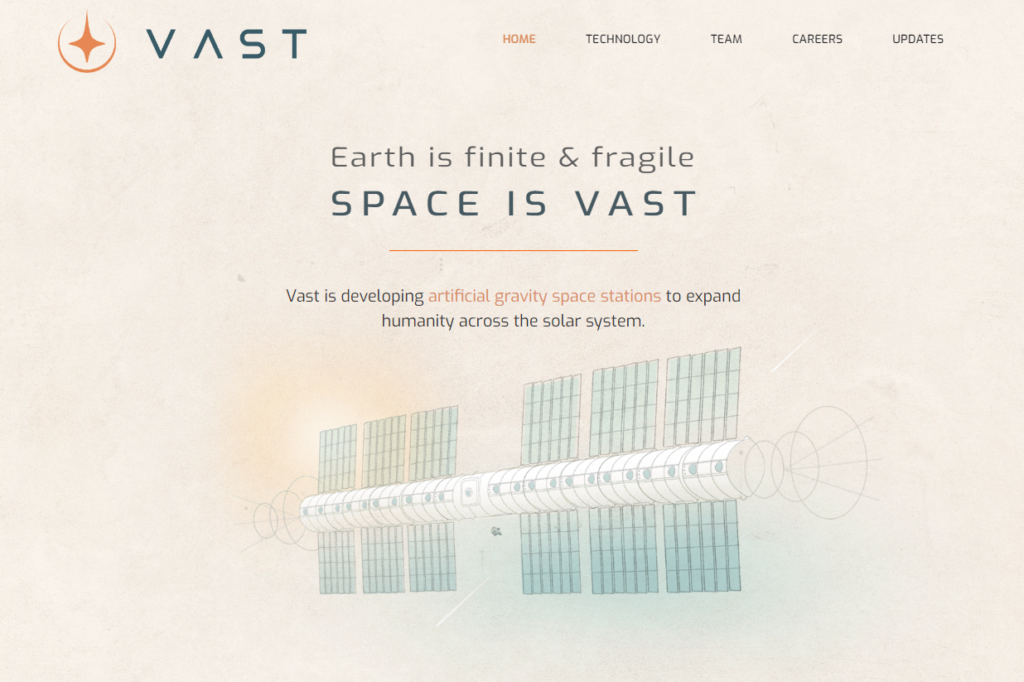

Earlier this year, Vast emerged from stealth with a bold goal: to build the world’s (or solar system’s?) first artificial-gravity space station.

The benefit of such a design, the El Segundo startup argues, is that it would offer “a healthier environment for long-term stays in space.” It’s still early days, but the thinking is that a large spinning structure would produce a gravity-like pull.

Vast is the brainchild of Jed McCaleb, a coder who cofounded American crypto startup Ripple and the Stellar protocol, along with creating Mt. Gox, the world’s first bitcoin exchange. Last month, Forbes pegged McCaleb’s net worth at $2.5B.

Vast’s vision takes shape

Ideas are cheap; execution is expensive. And building a space station is something that only a handful of superpowers and nation-states have been able to pull off to date.

“There’s never been a commercial station before,” McCaleb noted to Payload in an interview. That could change by the time the decade’s out—led by Houston unicorn Axiom, a bevy of developers have their sights set on privately operated orbital outposts and a continuous crewed presence in low Earth orbit.

What makes the company more confident that it may be able to move mountains, essentially, into orbit?

- The plan is predicated on SpaceX’s next-gen launcher—or a similar heavy-lift capability—coming online. “We believe that Starship will launch,” McCaleb said, and his company intends to take advantage of the larger fairing and cargo capacity.

- By taking Point #1 for granted, Vast is employing a “first principles” approach and can take more liberties with its station’s design.

- Vast will be self-funded for the foreseeable future. “I think in terms of raising outside money,” McCaleb noted, “the current plan is to put that off for as long as possible.”

- The company consists almost entirely of former SpaceX’ers (and, notably, counts Hans Koenigsmann as an advisor). It intends to continue to focus heavily on recruiting, McCaleb said, and nearly 4x headcount over the next year.

At this point, there are still quite a few unknown unknowns with regard to how—or if—Vast can get its idea off the ground. But the company has a new way of thinking about things, a bias toward speed, an experienced team, and less external pressure on the financing front.

Find our conversation with McCaleb below. Note: This interview was edited for clarity and length.

I am curious to hear about when you got interested in space. I suspect it’s not a newfound interest.

That’s right. I’ve been interested in space forever, basically, since I was a little kid. It’s just inherently interesting, like this whole expanse that you can go on into, and it’s just, it’s super compelling to me. And we’re alive during a time where the Earth has been completely explored already, so we haven’t had that opportunity. So space is that for us.

I think it’s super important that people get off the planet and into the solar system, essentially.

As for a commercial venture in space, was that a more recent development or have you always had that inclination?

I started programming when I was a little kid, and I’ve been in software forever. I kind of always told myself that if I was ever super successful, then I would do something like go mine asteroids or something like that. That was always kind of in the back of my mind. Somewhat half-joking, but actually wanting to do it, as this sort of big ambitious target that you can be driving for.

Well, the interplay between crypto and space reminds me of when ConsenSys bought that asteroid mining company a while back. That’s funny to think about. When did you pull the trigger on Vast and start to staff up? And what have you been up to specifically in the last few months?

So, I think we officially incorporated sometime last year, but we really didn’t get started in earnest until January of this year. That’s when we started actually hiring people and getting an office. So it hasn’t been that long…just a few months.

We have our initial concept of where we’re going. Our main focus over these past months has really been building a team. And, you know, it takes a lot of expertise to build a space station.

You need a lot of really talented, smart people in one room before you can make much progress. That’s kind of what we’ve been mainly focused on so far.

I know that there’s a ton of former Space X’ers on the team, including one on this call. What percentage of your team has worked at SpaceX?

Probably like 95% or something.

Oh, wow.

It’s just me and the admin that hadn’t been at SpaceX.

Rounding up, 100%. I hate to deploy this cliche but I’m gonna do it. You know, there’s Axiom, Nanoracks and Voyager, Orbital Reef, Northrup Grumman’s HALO…all these private space stations at various points of development and design. Why start from scratch, and what does Vast bring to the table that’s unique?

We’re just taking a very first principles approach to this problem. How do you put people—or allow people—to live for long periods of time in space? Right. So we’re trying to think from first principles, rather than be saddled with this legacy idea of how to do it.

And, you know, we believe that Starship will launch. Whether it’s Starship or some other large launch vehicle, I think it will really change the dynamic in space. Our idea is just not very mass-constrained.

We’re filling up the full volume of something like Starship [and to date] we’ve been using a fraction of its mass. We can design [the station] in a much faster way. The engineering costs are lower; the materials we use can be cheaper and slightly heavier; and maybe we can use more off-the-shelf parts.

And so all of this compounded allows you to do something at a drastically lower price point than what’s been done historically. The reason to start from scratch is because we can enforce that mentality. It’s very similar to the way SpaceX approached the problem of launch. We want to do something similar, but with habitations.

To what extent is the design of all of this and even like the user experience centered around artificial gravity? I know it’s a ways out, but you’re pretty deliberately not building a space station with weightlessness, as you say, given the adverse long term health effects.

Right. Once you have a spinning structure, it really changes a lot of things, right? It leads to a lot of new complications and things you have to figure out. It’s never really been done before. We are going to start with a zero-G station as a starting place.

But we quickly want to be building towards a bigger structure. Every aspect of the station gets impacted by this…by the rotation. Things like docking…

…that’s what I was about to suggest.

…are complicated. Even communications are complicated. Solar is different, too. Even controlling the station itself is different because essentially it has this huge angular momentum, like controlling a bicycle wheel. It’s very hard to turn, right?

As for the design, it’s like a long tube, right?

Mm-hmm. So, that will presumably be different modules all attached. The essential idea is we have this module that fits inside a Starship fairing. We launch it up and you can start connecting these models end to end. You get this big stack of Coke cans that you can spin.

I wanna ask where you land on buy vs. build? On one extreme, you don’t need to build a rocket from the ground up to create the station. But to your point, the spinning element and new design, there’s probably a lot that needs to be designed and developed in-house.

We’re trying to be pretty vertically integrated. I think everything is a trade-off. There’s some stuff that you can get off the shelf now that is perfectly fine. If there’s a higher cost for some component that you’ll just use once, maybe you just go ahead and buy it instead of putting up the engineering cost and development.

But in general, we have a bias towards building everything in-house. For the same reason it’s been successful for other companies…you’re not beholden to your suppliers. You can kind of control your destiny a little bit better.

Yeah. Are there core fundamental technologies that you need to develop or create for this?

That’s kind of the cool thing here, is that it seems very ambitious, more than it is. But there’s no new science we need to make. Everything is known, it’s just an engineering challenge. Can you execute on essentially what’s known is our real challenge. There’s some question marks of what rotation rate humans will be comfortable with, things like that, and some of those things we’re gonna have to figure out. But yeah, there’s nothing kind of fundamentally new to what we’re doing, which is kind of the cool part.

In the canon of sci-fi, are there analogs to what you’re doing that you draw inspiration from? I’ve seen so many rotation stations in sci-fi.

I mean, we’re kind of building like a spoke of the Stanford Torus. Or like one spoke of Arthur C. Clarke’s rotating station. The idea is eventually you could build a ring on this thing, but we’re focused on one spoke first, which gives you gravity, at least.

Next on my list of questions was dropping launch prices or a cost threshold that something needs to drop to for this plan, or strategy, to work. Is everything predicated on a post-Starship world?

I think it could still work if Starship for whatever reason doesn’t end up flying, but it’s definitely not as grand, right? Starship is a big rocket.

And you’re designing to take advantage of the bigger fairing and whatnot.

Yeah, that’s right. And our structure sort of really benefits from Starship, but I think the larger benefit and second-order thing is just that if Starship starts working, it’s lifting really a lot of mass to orbit and enabling lots of enterprise in orbit and bolstering that whole ecosystem. I’d expect that ecosystem to grow quite a bit, with humans doing all kinds of things.

For some of those things, or a lot of them, we’re gonna want humans in the loop in some capacity. That’s where Vast comes in. Some company wants to do something with a satellite on orbit and it’d be helpful for a person to snap two things together or whatever. Vast can provide this. I think there will be lots of things like that, where having a human in the growing ecosystem will be super valuable.

I see on your website that a future station could accommodate both crews and experiments, manufacturing, that sort of thing. How will those two coexist? Or how will the layout, I suppose, look?

Obviously, it’s super early for this kind of stuff. But there will be two ends, so maybe one’s industrial and one’s more residential. There’s lots of options here. We aren’t building like a space hotel, where it’s some sort of luxury destination or anything like that.

What we kind of think about internally is that we kind of want to do the same stuff that’s happening on the ISS. We want to support research. We also think of ourselves as an orbital machine shop, where people can build things in orbit.

There’s lots of reasons for why that’s valuable. I think it will allow people to build structures that don’t quite fit in the fairing, or slide in it, or can’t survive launch, or need some sort of deployment mechanism and set-up. So, really, we’re taking a more industrial focus for the station.

In the early days of Blue Origin, I’ve heard it described as a quote-unquote think tank where they were analyzing different concepts and ideas before they decided what they were going to build. Would you say Vast is at a similar stage or that you’ve moved past that?

I think we have a fairly good idea of what businesses we’re going to service. You can’t be totally sure because there’s never been a commercial station before, or where launch costs were so low, so you’re kind of entering this new world.

What we’re building is flexible enough and can be used in different ways, so I think we’ll be able to take advantage of whatever develops. That’s one of our principles as well: making sure we can serve lots of different needs and not just one particular niche.

The same exact caveat throughout this conversation applies here, but do you have any sense of timeline or ballpark of what a full station would cost? Or maybe let’s go with a definition of reaching initial operations on orbit.

It’s still a little bit early for me to speculate about timelines.

That’s fair. Space companies have been bitten in the butt by putting out timelines early, with those estimates coming to boomerang around on them.

Yeah. I will say that we are, we are trying to move quite fast and, you know, you alluded to a race earlier—we don’t really see it that way, but we would like to be the first station in space. Hopefully people will be surprised by how fast we move.

What will the headcount look like over the next year?

We’re roughly 25 now, something like that. I think a year from now we probably [will] be at around 80.

And you’re self-funded for now. When or why would that change? I mean, do you anticipate competing for NASA or other government contracts?

We definitely want to serve NASA and maybe other national astronaut programs. I think one of the reasons why there are so many people building space stations right now is because NASA has this CLD program happening. So, we certainly want to compete for that, and I think we’re a really good fit for what they’re looking for.

Hopefully there will be some funding from that. We obviously want to be revenue-generating, and to serve commercial customers as well, so that there’ll be revenue from this.

I think in terms of raising outside money, the current plan is to put that off for as long as possible. What we’re doing is a capital-intensive project, and you have to have really long time horizons and patience. We don’t want the vision to get warped, so it seems better to keep it focused on just me.

Will it initially be crewed? I think it’s interesting you mentioned humans in the loop, and to consider the automation question. How long would it take for a crew to arrive after initial launches?

The current concept is to launch one of these modules. It’s pressurized, fully contained, and ready to go. We make sure everything’s operational and then we launch up something like Crew Dragon, where we can put people in. Other than checking things out, there’s no complicated deployment or anything like that will have to go into it.

Solar panels left unfurled, things like that, but nothing too intense. And that’s for the single, free-floating module. But then for building the actual stick, yes, then there’s a lot of assembling different components that people won’t be involved in. That would be a larger endeavor.

Where would the final parking spot be?

Right now, we kind of want to stay just under the Van Allen belt. We want it high enough where the orbit’s not going to decay, but we want to be protected by the Van Allen belt so it’s not exposed to a lot of radiation.

Have you been studying the ISS in detail?

Absolutely. Obviously, we’ve learned a lot from the ISS and how they’ve done things. Again, I think we want to take a first principles approach, but we still need to learn from what other people have tried. That’s a huge component of it. It’s been up there for a long time, but there’s a lot to learn from it.

It’s definitely starting to show its age. That’s everything I wanted to ask. Anything to add?

I think the one thing I’d wanna reiterate is that the space ecosystem is changing a lot and will change a lot over the next few years. With Starship, and what Relativity’s doing, we can get so much more mass to orbit at such a lower price. The dynamic up there is gonna change quite drastically and the ecosystem’s gonna explode.

And Vast really sees itself as a key component for being able to increase the capability of what people can do up there.