An increase in planet-warming greenhouse gas levels is having an unintended effect in LEO—extending how long space debris hangs around in orbit.

While these gases trapped in Earth’s atmosphere are warming the planet, they’re cooling LEO, which reduces drag on satellites and debris objects, according to a study released this week. This delay in deorbiting increases the risk of overcrowding and collisions.

“We rely on atmospheric drag to remove debris objects,” study lead author William Parker of MIT told Payload. “If you’re going to abandon something in space—which is a bad idea—it’s becoming an even worse idea over time.”

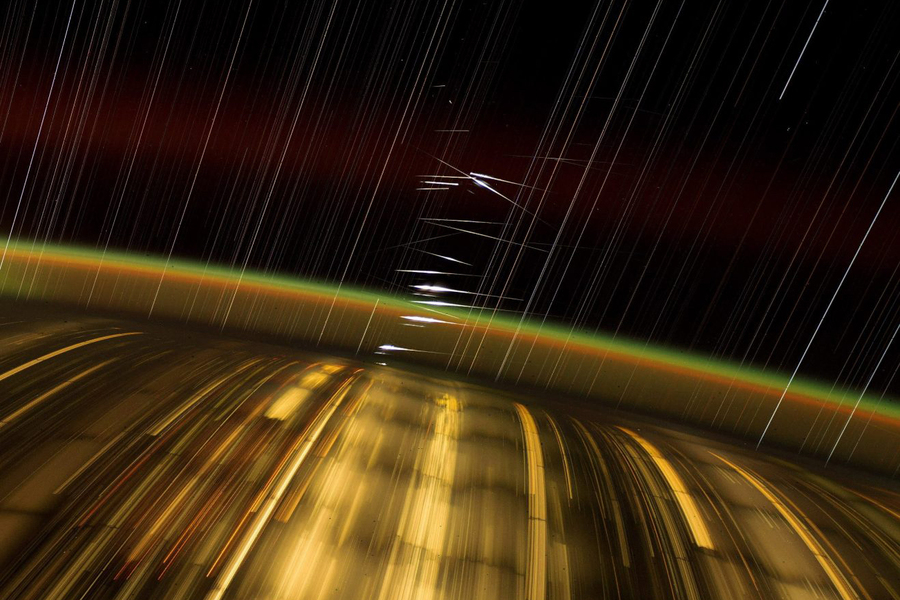

Ebb and flow: The climate change impacts we’re familiar with are primarily due to heat trapped by CO2 and other GHGs in the troposphere, Earth’s lowest atmospheric layer. Higher up, the thermosphere—home to ISS and most communications, weather, navigation and defense satellites—naturally expands and contracts over decades in response to the Sun’s 11-year activity cycle.

- During periods of low solar activity, reduced radiation cools and contracts Earth’s upper atmosphere. The decreased density means less drag on the roughly 10,000 active satellites and 25,000 pieces of trackable debris objects in LEO, allowing them to stay in orbit longer.

- Recent observations have highlighted another key factor: Trapping more GHG-driven heat in the troposphere prevents it from wafting upward, leading to a cooler thermosphere.

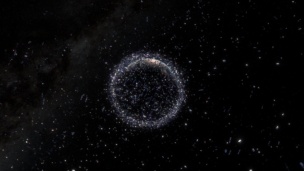

- The new study’s simulated reductions in atmospheric density predicted a 60% decrease in the number of LEO satellites that could be sustainably accommodated during solar maximum and an 82% decrease during solar minimum by the year 2100.

Hitting the limit: The year 2100 may be far off, but the satellite megaconstellation trend is already crowding a very small portion of space, highlighting the need to declutter proactively by deorbiting assets before they become debris, Parker said.

“It’s in everybody’s best interest to make sure that what we’re doing is sustainable long-term,” he said.