Astranis announced a $200M Series D round this week—the largest US venture raise for a space company thus far in 2024, according to public reports and data assembled by Space Capital, which also ranked the company as the seventh-largest private space infrastructure firm at its reported 2023 valuation of $1.6B.

Now, the GEO satellite operator is funded to build nine of its current model satellites in the next two years and complete the development of a new, more capable satellite called Omega, expected to be ready for launch in 2026. Payload caught up with CEO John Gedmark to learn more about the deal.

This transcript has been edited for length and clarity.

It’s been a tough couple of years for space companies raising private capital. How did you convince investors like Andreesen Horowitz and BAM Elevate to make this bet on your business?

We have a pretty incredible roster of customers for satellite projects around the world. We have also started an inflection point with our business with the US government—we’re in prime position here to provide communication services for the armed forces overseas. It all adds up to being in a pretty good position as a company. No single silver bullet there—it’s just a collection of a lot of great execution by the team on many fronts.

What makes your firm different from others building low-cost satellites?

[In GEO,] your satellites are just taking massive doses of radiation all the time. It is a next level challenge compared to LEO. So we have spent a lot of time and energy and developed a lot of expertise around designing electronics that can do that and that are still very low cost.

This capital is going to help scale your satellite factory to produce up to 24 satellites a year. How do you do that in San Francisco?

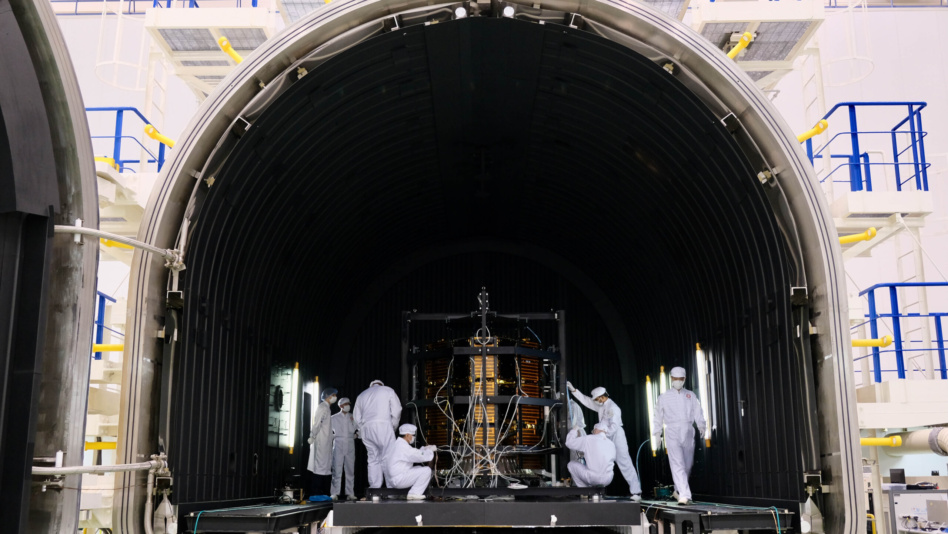

We are very proud to call San Francisco, CA our home for manufacturing. This is the single densest collection of engineering talent in the entire world. That is both hardware and software, and the software piece is really important, right? These satellites are software defined—something that we knew would be key from day one was having the flexibility of being software defined and we knew that this was the right location for us.

What we realized in looking across some other companies that have really done things in a new way in the last few years, are the benefits of having your engineering teams and your manufacturing and production teams all under one roof. Then you have these super fast iteration cycles where you can have somebody see something on the production line, or a design engineer spot something while they’re at their desk, and they can just walk down to the factory floor in an instant.

How are you managing the transition to the new Omega spacecraft?

You have to be able to walk and chew gum at the same time. We wouldn’t be doing it if there was a huge amount of overlap [between the two spacecraft]. The rare thing is…when a specific upgrade is ready, meaning the next version of the hardware is fully tested, qualified, we can roll that into a block of satellites that’s coming off the production line. Or we can bundle up a whole bunch of those improvements and say, it’s the right time to draw a line here, move to a whole new version of the satellite, [and] start a new production line.

You also said that no other country can develop GEO satellites at this price, which no doubt stands out in Washington.

It is very important that we be able to achieve resiliency in these important national security space capabilities, and we don’t have that today, right? We have just put up giant satellites that cost hundreds of millions or a billion dollars per satellite, and there’s not very many of them. So those make very tempting targets for adversaries.

There’s a better way: you deploy large numbers of small satellites, as long as they’re a low enough cost, and then all of a sudden you have this real resiliency there. And that is the name of the game. It’s resiliency. And the Space Force wants it in every orbit, LEO, MEO, GEO. I think we’re pretty well positioned to help them out in some of the higher orbits

As Astranis’ workforce has grown, what are the pain points you see while hiring?

We find it particularly challenging to find people on the production side, technicians, machinists. They’re incredibly important skills, people develop these skills over years, and sometimes they can be really hard to find. I do think that is something that I’m hoping we as an industry solve over a longer time frame here, we can get more people to go into these highly skilled jobs.

I have to ask—any updates on your next launch on the Falcon 9, which was expected to launch before the end of the year?

I will refer you to SpaceX for all Falcon 9 related things; we are getting very close.