In 2011, astronauts departing the ISS on board the final space shuttle flight left behind a US flag for the next American-launched crew to retrieve and return to Earth.

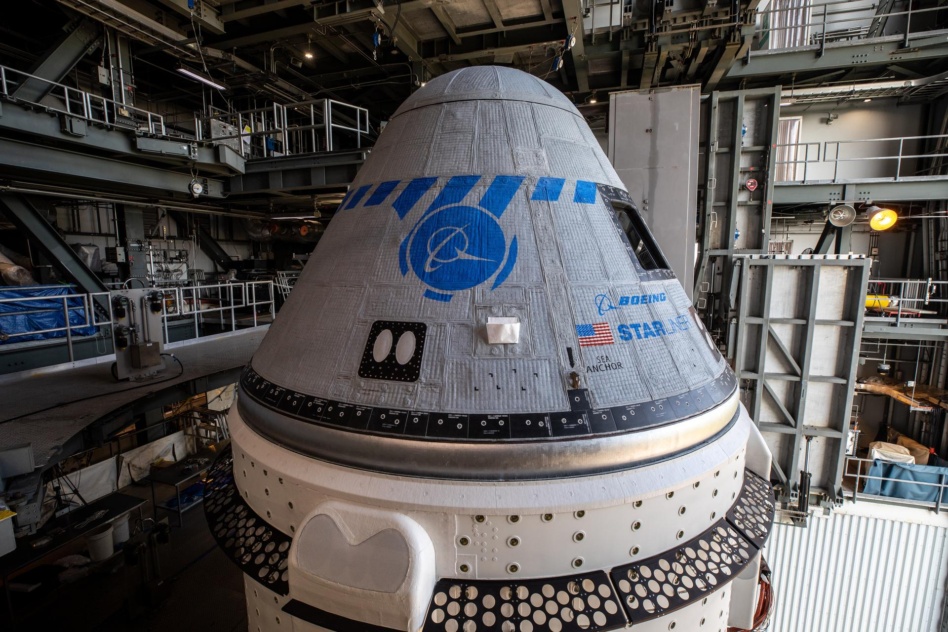

Boeing was once seen as the presumptive winner in the game of orbital Capture the Flag. As it prepares for the first crewed flight of its Starliner crew capsule at 10:34pm ET today, the flag is long gone, captured in 2020 by SpaceX, the one-time underdog that beat Boeing to the station by nearly four years.

Looking back: The Starliner mission has been one of the most challenging spacecraft development programs in recent memory. But it wasn’t always this way. Back in 2016, Boeing was celebrating a century as America’s leading aerospace company. Chris Ferguson, a former NASA astronaut, was then leading the development of a new astronaut-carrying space capsule for the ISS—and planning to make the first flight himself as a commercial astronaut.

“I’d like to think that all the technical issues, all the things that we knew were design issues going in [and] that we discovered along the way and we’ve had to pound flat…I’d like to think they’re all behind us,” he said then. “I hope they’re all behind us.”

They were not: A series of missteps led the vehicle to launch seven years later than anticipated. Boeing and the other participant in NASA’s commercial crew program, SpaceX, were originally aiming for certification in 2017; those dates slipped to 2019 almost immediately. SpaceX was able to launch its Dragon capsule with crew in 2020 and begin regular flights that year. Boeing, meanwhile, continued to struggle.

- During an uncrewed flight test in 2019, a series of software and execution errors could have led to a “catastrophic spacecraft failure,” per NASA’s safety advisory panel. Worse: NASA officials said Boeing should have caught the errors in thorough pre-flight testing.

- A 2021 attempt to re-do the uncrewed flight test was scrubbed on the pad due to stuck valves in the Starliner vehicle, forcing a re-design that pushed a successful uncrewed flight test to May 2022.

- Ahead of the first crewed flight test in 2023, engineers uncovered problems with the capsule’s parachutes—and learned hundreds of feet of tape wrapped on wire harnesses in the vehicle were flammable. Fixing those problems brought us to today’s flight.

The party line is that this has been a learning experience: “I have seen a tremendous change in Boeing culture since the first orbital flight test,” NASA’s commercial crew program manager, Steve Stich, said last year.

If culture comes from the top, the change makes sense—we’re on the third Boeing CEO since the company unveiled Starlinerin 2010, and the original program leadership, including Ferguson, former SVP Jim Chilton, and former VPs John Mulholland and John Vollmer, have left the company or moved on to other roles.

Asked to assess Starliner’s development on Friday, current program manager Mark Nappi suggested that the experience wasn’t anything out of the ordinary. “It’s pretty typical that a human spaceflight vehicle is about a ten year period,” he said.

Well, maybe: If you start your clock when the program of record began, it took the space shuttle nine years to perform a crewed flight, and the SpaceX Dragon just six. Boeing unveiled the Starliner and started receiving development funding in 2010, but it’s been a decade since the full contracts were awarded.

Cost comparison: The Planetary Society hailed SpaceX’s Dragon as one of the lowest cost human-rated spacecraft ever built, developed for about $2.6 billion. NASA spent more than $3B on Starliner development costs, and Boeing has reported an additional $1.5B of losses on the fixed-price contract.

Alongside Boeing’s recent aviation struggles, Starliner has dinged the company’s reputation as a world-leader in engineering. A successful flight to the ISS could help kickstart a turnaround narrative—but the company will need to figure out how to keep Starliner flying past the end of the decade. More on that after the flight…