NASA Administrator Bill Nelson said yesterday he would leave two options for the next administration to get scientific samples home from Mars, an over-budget $11B mission that the agency paused in 2023.

- Use JPL heritage technology to deliver a smaller lander to collect the samples and send them into orbit to rendezvous with a European-built Earth-return spacecraft. Cost: Up to $7.7B

- Use an unidentified commercial heavy-lift lander to deliver and perhaps return the samples. Cost: Up to $7.1B

Either option, Nelson said, would require an immediate commitment from lawmakers of $300M to begin launching by 2030 and return thirty Martian rock, soil and atmospheric samples between 2035 and 2039.

Downscale: After months of studies, NASA scaled back its plans for the mission, cutting vehicle mass and switching power sources. Still, MSR would be one of the most expensive NASA science missions ever.

“As proposed, a mission that would cost $7 billion and not return samples until 2036 at the earliest seems to be out of pace with what the incoming administration is looking for,” Casey Dreier, chief of space policy at the Planetary Society, told Payload.

Who else? NASA awarded eight companies up to $1.5M to conduct 90-day studies of how to do MSR faster and cheaper, but details remain scarce.

Nelson mentioned both SpaceX and Blue Origin, and Nicola Fox, the head of NASA’s science mission directorate, discussed the agency’s interest in commercial heavy landers generally. “They dance around, but there’s only really one viable, realistic player, which is SpaceX and Starship,” Dreier said.

“The commercial aspect is a prayer that there will be a commercial, viable option, because it just does not exist,” Dreier said. “The fundamental decision that Bill Nelson has given to the incoming administration is, do you go with something you know, or do you go with something you don’t?”

Excuse me: Rocket Lab, the other spacecraft company with a regular launch cadence, pitched its own end-to-end MSR concept to NASA. Unmentioned in the agency’s briefing, the plan targets a sample return by 2031 at a dramatically lower cost of $4B.

Richard French, Rocket Lab’s VP for business development, said that’s possible thanks to vertical integration, ditching ESA’s contribution, and adopting simple concepts of operations that don’t require in-space refueling or vehicles based on expensive human-rated systems.

“We’re hopeful that the new administration wants to lean forward into commercial,” French told Payload. “There needs to be fair and open competition. Some companies are overextended, they aren’t meeting their obligations as already assigned. We’re not one of those.”

Make it work? Let’s not forget incoming President Donald Trump has previously suggested Moon missions are a waste of time, and his advisor Elon Musk is laser-focused on Mars. Given that, officials could pitch MSR as a risk reduction and tech demo project for a future human spaceflight program targeting the red planet.

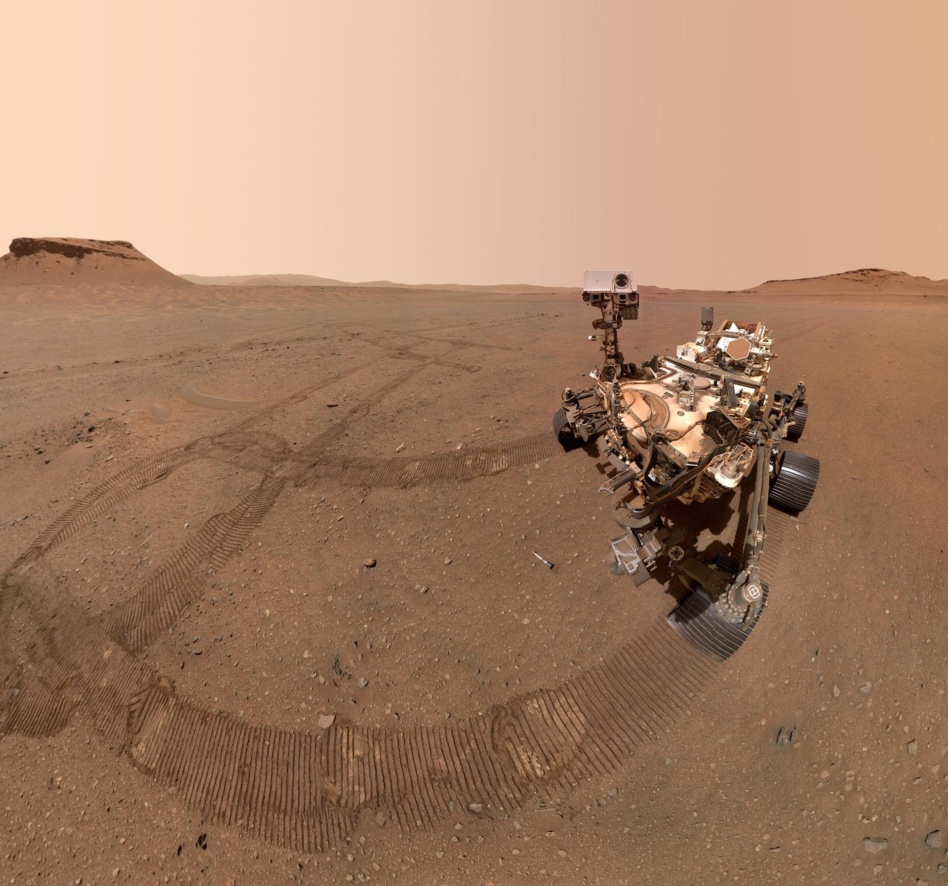

But if NASA elects to wait for a mission in the 2030s, the current architecture would require the Perseverance rover to return to its landing site and wait for its arrival in order to deliver the cached samples.

“Essentially, this would prematurely end the exploration phase of NASA’s last great science rover, quietly draining its battery and waiting for a mission that might never come,” Dreier said.