Ed. note: This is Payload Research analysis. You can sign up for our Research newsletter here.

China held its annual Space Day conference last week, unveiling new insights into the space program’s hardware development. Updates included:

- Confirming it is on track to land crew on the Moon by 2030

- Outlining its two-part 2035 and 2045 ILRS moon base development phases

- Timing on Long March 9 (aka China’s Starship)

- Tianwen-3 Mars sample return mission

- Orienspace’s new Galactic-2 rocket

As always, timelines should be viewed with caution. Creating graphics is easy, but developing crew-rated hardware is complex and always riddled with cost overruns and delays. While the pomp and circumstance at the summit may be a bit overselling, it does underscore China’s commitment to its space ambitions and the funding required to make them a reality.

How much does it cost? Euroconsult estimated China spent ~$12B on its space program in 2022, a figure far less than the ~$55M for NASA + Space Force.

Although, pinpointing China’s space program appropriations is really more of a dart-throwing exercise, given the veil of secrecy around these matters, and we believe the actual funding numbers could be substantially higher.

With a 2030 crewed lunar landing date set, the program has been elevated to a matter of national pride, increasing the available funding pool to pull from.

“China’s funding is a bit of a black box,” Kevin Pollpeter, a China space program expert at CNA, told Payload last year. “But if they felt they could not afford to go to the Moon, they would not have gotten it approved.”

China Reaffirmed its 2030 Crewed Lunar Landing Goals

China reiterated last week that it is on schedule to land its first crew on the lunar surface by 2030.

“There is a prestige factor involved. Going to the Moon would be a big feather in China’s cap,” said Pollpeter. “This is a way for them to demonstrate themselves on the world stage.”

China’s lunar landing 101: China’s crewed lunar mission involves two launches: one carrying the crewed module and the other carrying the lander. The two spacecraft will rendezvous in lunar orbit to transfer the taikonauts before the crew of two descends to the lunar surface for a short six-hour mission.

China commented last week that work is advancing with its three primary mission vehicles.

- Long March 10: Development and prototyping of the new super-heavy lift Long March 10 rocket is progressing, with its engines recently completing critical static fire tests.

- The rocket is designed to transport 70 metric tons to LEO and 27 metric tons to trans-lunar injection, similar to the capabilities of NASA’s SLS rocket.

- The country is targeting a 2025-2026 test launch.

- Spacecraft + lander: The Mengzhou spacecraft and the Lanyue lander are also moving through design, which includes thermal product testing.

Setting expectations: The country is still in the early stages of developing its crew-rated hardware, but with a virtually unlimited budget and a *relatively* straightforward lunar landing mission architecture, the timeline is certainly possible.

Compared to Artemis: NASA has penciled in an Artemis III crewed lunar landing for 2026. While SLS and Orion vehicles are generally in good shape, the complex Starship lunar lander architecture development will likely push that date back—possibly by a couple of years—which leaves the door open a crack for China’s crewed mission timeline to possibly rival NASA’s.

However, the two missions are substantially different. China’s mission sidesteps the technical challenge of in-orbit refueling, which is required to transport the cargo volume necessary for extensive lunar development. China’s six-hour mission is a flag and footprints operation, more akin to Apollo than to Artemis.

Artemis is designed to transport enough cargo to the lunar surface to sustain a lunar base. The payoff of investing in the complex Starship lunar landing architecture—which will likely require 10+ in-orbit refuelings per trip—is that it will allow for the transport of a staggering 100 metric tons to the lunar surface.

Building ILRS in Two Phases

After China accomplishes the flag-planting mission, it will then look to build out its International Lunar Research Station (ILRS) with larger vehicles. Last week, China said it would construct its lunar station in two phases.

- 2035: China plans to build a bare-bones base with basic science and life support.

- 2045: The second phase will feature scaled facility infrastructure, an orbiting lunar station, and a shift in focus to a Mars mission.

Although—as we noted before—decades-long forecasts should be viewed with skepticism, as they mainly serve as rallying calls to boost excitement and offer little in the way of concrete projections.

2032 Target Launch of its Mega-Class Long March 9 Rocket

China announced that it aims to launch its next-gen Long March 9—which looks an awful lot like Starship—on its first test flight by 2032. The Long March 9 is designed to carry 150T to LEO…sound familiar?

State officials said they plan to incorporate partial reusability in the vehicle design, with full reusability targeted for the 2040s. The timeline puts China at least a decade behind US mega-lift rockets, with Starship having already completed a successful IFT-3 mission and progressing toward reusability.

Orienspace Detailed Galactic-2 Rocket

Chinese launch startup Orienspace successfully launched its first rocket, a solid-propellant Gravity-1, earlier this year. They are now looking to advance to Gravity-2, a liquid-propellant reusable rocket, with the first launch slated for 2025.

Gravity-2:

- Transporting 21.5 metric tons to LEO when expendable.

- Transporting 17.4 metric tons to LEO in a reusable configuration.

- The first stage is designed to be reused 30+ times.

The first launch is slated for 2025.

Highlighting Tianwen-3 Mars Sample Return Mission

With NASA’s Mars Sample Return mission struggling to find a path forward, China is doubling down on its Mars sample return plans, confirming its Tianwen-3 mission is on track to launch in 2030. Officials added that work is underway on developing its sample lab.

Wu Weiren, a key designer of China’s lunar programs, alluded to NASA’s MSR issues at Space Day last week. “Currently, looking at the progress of various countries around the world, our country is expected to become the first country to return samples from Mars,” said Wu Weiren.

Tianwen-3 mission architecture: The Mars sample return mission consists of an orbiter and a lander.

- The lander will touch down on Mars, collect rock and soil samples.

- With samples in hand, an ascent module will be launched back into Mars orbit.

- The samples will be transferred to the orbiter, which will then return them to Earth.

The mission architecture is similar to NASA’s design.

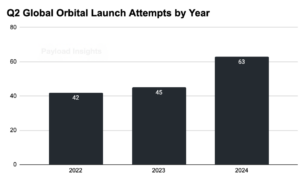

+ China Launch Stats

China and the US lead the world in orbital launch attempts. In fact, in 2020 and 2021, China outpaced US launch attempts. The two countries also launch a similar number of defense payloads to orbit.