NASA is on pace to exceed $100B of Artemis funding by FY26, according to nominal dollar data from OIG, NASA budgets, and Payload analysis.

The program—which has penciled in its first crewed lunar landing by 2026—is one of the most expensive in NASA history.

The enormous costs largely accrue to development of the mission’s vehicle. This piece will detail the investment in developing SLS, Orion, HLS, and Gateway, comparing the spend to the Apollo program and present-day commercial launch vehicles.

Quick refresher: The Artemis program consists of four major vehicles: Space Launch System (SLS), Orion, Gateway, and the Human Landing System (HLS).

- SLS: SLS is the most powerful crew-rated rocket since Saturn V and is tasked with transporting the Orion capsule to lunar orbit. NASA owns the rocket, which was largely contracted out to Boeing (core stage), Aerojet Rocketdyne (engines), and Northrop Grumman (solid rocket booster).

- Orion: Lockheed Martin builds the Orion spacecraft for NASA (development goes back to the Constellation program). ESA and Airbus contribute the spacecraft’s service module. The vehicle carries astronauts to and from lunar orbit as a free-flyer, or it will connect with Gateway.

- Gateway: The lunar space station will provide the crew with additional power, life support, and science capabilities while orbiting the Moon. Gateway is an international project, with ESA, JAXA, UAE, and US commercial companies (most notably Northrop Grumman and Maxar) contributing to its build.

- HLS: NASA awarded lunar lander contracts to SpaceX’s Starship and Blue Origin’s Blue Moon. These landers will rendezvous with crew in lunar orbit and transport them to the Moon’s surface. When their work is done, the HLS vehicles will lift off from the surface, returning the crew to Orion for transport home.

High-Cost Artemis Vehicles

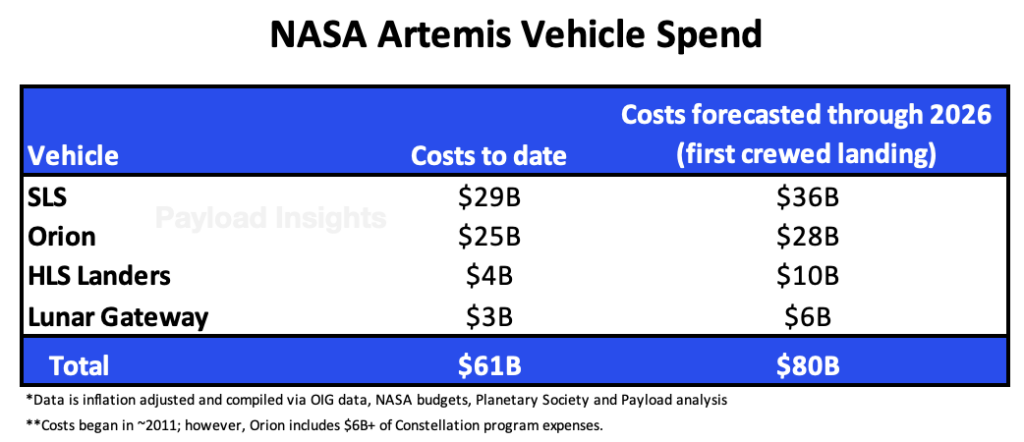

Focusing on just the vehicles, NASA has spent over a decade and a staggering ~$61B (inflation adjusted) developing the Artemis hardware. The hefty price tag produced the most powerful and capable crew-rated vehicles built since Apollo.

- NASA expects total vehicle costs to reach ~$80B by NASA’s first crewed lunar landing in 2026. Should the timing of the Artemis 3 landing be further delayed (a likely scenario), the expenditure incurred before we return boots to the Moon will increase.

Homing in on R&D: TThe majority of vehicle expenses fall within R&D. Payload imperfectly defines R&D as all costs incurred before the first launch.

(Calculating R&D is imperfect, as multiple vehicles are in the works at the same time—for example, NASA is currently paying for 3 HLS landers. Historical SLS and Orion data compiled by the Planetary Society.)

To put Artemis vehicle R&D in perspective, we will compare the costs to Apollo vehicles and the current fleet of commercial vehicles.

Comparing to Apollo

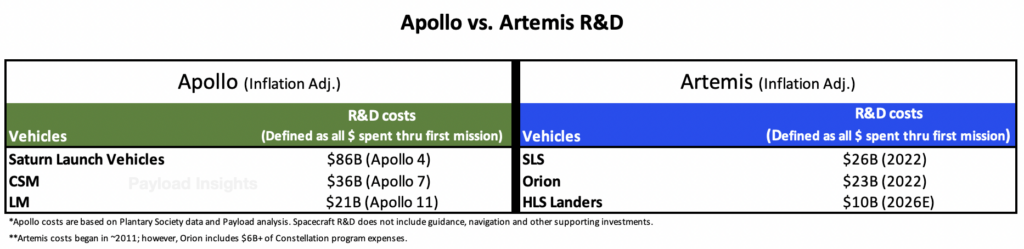

Like Artemis, Apollo had three primary vehicles: the Saturn V rocket, the Command and Service Module (CSM), and the Lunar Module (LM). NASA’s Saturn V launched the CSM + LM into lunar orbit, and the LM carried the crew to and from the lunar surface.

Vehicle comparison: Below is a comparison of vehicle R&D costs. Again, we imperfectly define R&D as all mission costs incurred until the first mission.

Artemis’s costs are meaningfully improved compared to the Apollo program.

However, Apollo vehicles were developed over 60 years ago as novel tech, and given the rapid cost reductions witnessed in other advanced hardware during that period, frustration with Artemis’s high price tag is justifiable. The disappointment is particularly pronounced when we juxtapose these expenses with the costs of current commercial vehicles.

Comparing SLS to Commercial Options

SLS is the only crew-rated vehicle capable of a lunar mission.

SLS (95T to LEO expendable):

- Development costs: $26B

- Cost to launch: $2B per launch (!)

- Other notes: Currently the only crew-rated rocket capable of a lunar mission

Falcon Heavy (63.8T to Leo in expendable configuration):

- Development costs: $500M development costs. $900M of total costs when including Falcon 1 and Falcon 9 R&D costs are included

- Cost to launch (internal): Less than $45M (reusable), per Payload analysis

- Other notes: Not crew-rated

Starship (250T to LEO) expendable configuration:

- Development costs: Expected to hit $10B

- Fully reusable goal

- Not crew-rated

- Less than half the R&D cost of SLS

- Cost to launch (internal): Payload estimates Starship will cost ~$100M to build and expend in a forward-looking/post-R&D model. Full reusability will significantly lower future launch costs.

- Other notes: Has not yet reached orbit, and the path to crew-rated launches is unclear.

Comparing Orion to Commercial Spacecraft

Orion is currently the only vehicle capable of a lunar mission, but the development costs have soared passed crewed LEO spacecraft.

$23B Orion R&D

- Includes $6B+ of Constellation program spend

- Orion is significantly larger than Crew Dragon and Starliner

$2.8B Estimated Crew Dragon R&D (per Payload analysis)

- Nominal dollars, includes Cargo Dragon costs and estimated SpaceX out of pocket expenses

- Crew Dragon is not deep-space rated

$4.3B Estimated Starliner R&D: (per Payload analysis)

- Nominal dollars and includes $2.8B from NASA and $1.5B of Boeing cost overruns

- Has not yet been crew flight tested and is not deep-space rated

The Cost Plus Contract Pivot

NASA contracted out the SLS and Orion development under cost-plus agreements, a contract structure that provides little incentive to minimize expenses.

Cost-plus contracts 101: NASA agrees to reimburse contractors’ costs, even when they increase far beyond the original budget. Cost-plus contracts can often (but not always) allow NASA to maintain ownership over the hardware. After getting burned repeatedly with cost overruns, the space agency has adopted a more firm stance against the cost-plus approach, labeling it a ‘plague’ and committing to fixed-cost contracts whenever possible.

Fixed-cost contracts 101: NASA pays a fixed fee for the entire project, regardless of actual costs the contractor incurs. Fixed cost contracts can often (but not always) be used to buy services, allowing the contractor to retain ownership of the vehicle.

Lunar lander pivot: Unlike SLS and Orion, NASA doesn’t own the HLS hardware. Instead, they pay a fixed price for services.

The HLS contracts are priced modestly ($2.9B for Starship HLS 1 and $3.4B for Blue Moon HLS), potentially saving NASA billions of dollars…that is if the complex Starship and Blue Moon architectures are proven successful.

- Blue Origin believes total Blue Moon lander costs will likely hit $7B, meaning the company would cover roughly $3.6B of expenses.

- SpaceX will also contribute a significant amount of out-of-pocket expenses to Starship HLS development.

Handing over the keys: NASA is pushing plans to transfer SLS ownership to a Boeing Northrop JV. The move would allow NASA to put SLS on a launch services contract rather than own the rockets. A potential NASA SLS service contract would cover Artemis missions 5 through 9.

(Claire Stevlingson contributed research to this piece)