Two US companies have proved that industry can land on the Moon. Now, startups are tackling the next challenge: keeping those missions running for years instead of weeks.

Why it matters: Generating or harnessing power on the Moon is critical to carrying out long-term missions. Firefly’s Blue Ghost lunar lander operated on the Moon for ~14 Earth days, which is the length of one lunar day. But it shut down with the arrival of lunar night (which also lasts for roughly two weeks on Earth), since the lack of sun and plunging temperatures make continued operations without generating energy impossible.

The Artemis program is all about a sustained lunar presence. Whether that includes robots or people, it’s going to require a power source for any operations longer than about two weeks.

Multiple choice: Companies trying to solve this issue are primarily split into two camps: solar and nuclear. However, experts say this isn’t an either/or situation.

“It’s really just pros and cons. One shouldn’t win out,” said John Thornton, the CEO of Astrobotic. “It should be a combination of them both in different cases.”

Some of the benefits and challenges of each power source include:

- Solar power is likely to be quicker and cheaper to set up, since solar grids already exist terrestrially and solar panels have been flown in space for decades. However, it only works where there’s nearly-continuous sunlight (so no bueno for lunar night) and pesky Moon dust can cover solar panels.

- Nuclear power is expected to be more expensive with a higher regulatory burden. But it has powered government deep space missions for decades and can provide power anywhere, including in permanently shadowed craters, where sunlight will be harder to use in the quest to mine water ice. Plus, it easily provides heat—important for keeping spacecraft warm to at least hibernate through lunar night.

Here comes the sun: Astrobotic may be best known as a lunar lander company that’s preparing to fly its Griffin lander—the largest of the CLPS spacecraft—this year. But Thornton said that when the Pittsburgh-based startup began looking at what they should be using the lander’s larger capacity for, power was an obvious choice.

“If you have power at the poles of the Moon, where everyone wants to go, missions can last for years on the surface rather than weeks,” he told Payload.

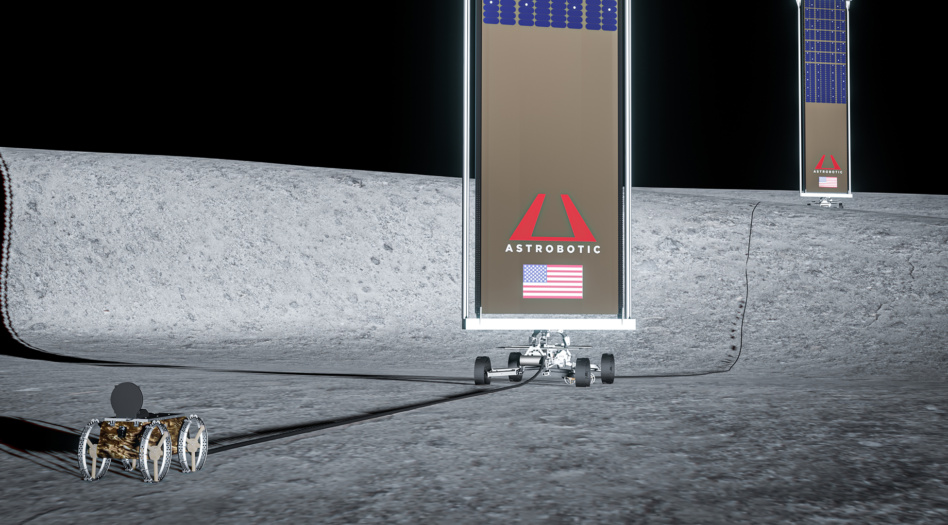

The company is working on a solar power grid on the Moon, aptly named LunaGrid, which Thornton believes can be built and deployed for less than $500M.

- The system would include solar arrays at a high point on the Moon’s pole that gets sun nearly 24/7, with batteries to cover the same amount of time in shadow.

- Rovers would move out from that central hub spooling out a power cable, bringing power to shadowed areas, rovers or astronauts on the surface, or science instruments in an “octopus approach,” Thornton said.

Astrobotic is preparing to test this tech for the first time in 2028 with its LunaGrid-Lite demo, which will send a rover 500 m from a lander and aim to send power back and forth, Thornton said.

Roll out: Redwire is also working on bringing solar power to the lunar surface by repurposing its roll out solar array—which has already been tested in deep space on NASA’s asteroid redirection mission—to generate power on the Moon. A lot of the tech can transfer over, according to Al Tadros, chief technology officer at Redwire. But the company is figuring out how to deploy the arrays in lunar gravity (which is different from deep space) and how to retract and relocate the solar cells for different missions.

“We understand solar cells and arrays very well. We use them in space all the time,” Tadros said. “Without clouds, you’re pretty much assured that if the sun is still there, you will be seeing sunlight.”

One limiting factor? The amount of payload that can be carried to the lunar surface. But Tadros predicted larger spacecraft working to head to the Moon from Blue Origin and SpaceX could help overcome that hurdle, making it easier to deliver large amounts of infrastructure.

Build it and they will come: Thornton sees an existing market for a lunar power grid among sovereign space agencies. But he also sees generating power on the Moon as a “tipping point” for a whole host of lunar business plans, explaining that power needs to be in place before other efforts like mining or long-term exploration can happen.

“One of the hardest things when looking at the Moon is if you’re limited to only a week or two [of operations], it’s hard to make the business case close,” he said. “If it costs $10M to get there, you have to make $1M a day. That changes when you can last for years…It opens up a whole new world because the price point of operating on the surface of the Moon will drop dramatically.”

One key to opening up these possibilities to the global space industry is the adoption of a common charging port, Thornton said. Since lunar regolith would quickly clog traditional plugs, Astrobotic’s proposal is a wireless charging system that would allow rovers, astronauts, or power tools to get closer to the pad and charge up.

Beam me up: Other companies are exploring collecting solar power in cislunar space and beaming it to the Moon. Star Catcher is working to build a power grid in LEO that can collect solar power and beam it to satellites in higher concentrations—technology that could be “transformative” for lunar operations, CEO Andrew Rush said.

The idea would be to collect solar power in cislunar orbit and send it to spacecraft on the Moon to help keep them alive longer, potentially beam power into shaded craters, or save missions for landers that land wrong (for example, with only one solar array unfurled or facing the wrong direction.)

For now, the company has focused its business case on LEO, but Rush said he could see the technology playing a role in a future vibrant lunar economy with an anchor customer to start.

Go nuclear: It’s a matter of when commercial missions will begin to use nuclear power on the Moon, not if, according to Zeno Power CEO Tyler Bernstein. The tech already has a long history of being used on government missions dating back to Apollo. More recently, China has harnessed nuclear tech to keep science experiments running 24/7 on its Chang’e-4 mission to the far side of the Moon.

“If we want to have long-term resilient operations on the lunar surface, we need to learn how to survive and eventually operate during the lunar night,” Bernstein said. “That requires heat and electricity independent of the sun.”

One challenge? Keeping pace with the exponential growth expected in commercial missions to the Moon with the limited supply of plutonium-238—only enough for a couple missions per decade at a high price tag, Bernstein said. Because of this, Zeno Power is using two other radioisotopes in more abundant supply to allow it to scale alongside the rest of the industry.

The loosening: Another hurdle for nuclear tech to come is burdensome regulations, though the government has taken steps to make it more straightforward for commercial space missions to use nuclear power. President Donald Trump signed a presidential memorandum in 2019 easing the rules around launching spacecraft with nuclear systems onboard, including creating a tiered system to evaluate risk.

Zeno Power is working with the government to get approval to launch its first mission in 2026. It is working on multiple programs with government agencies, including a Space Force program to fuel satellites that can maneuver without regret between different orbits and a $15M NASA tipping point contract in conjunction with Blue Origin and Intuitive Machines.

Survive, operate, thrive: Bernstein laid out a three-phase approach to adopting the use of nuclear tech on the Moon:

- Survive: Using a radioisotope heating unit to keep spacecraft alive but in hibernation during lunar night

- Operate: Providing power to continue scientific research or other operations during the two-week dark period

- Thrive: Establishing nuclear reactors to facilitate more power-heavy missions such as using lunar resources