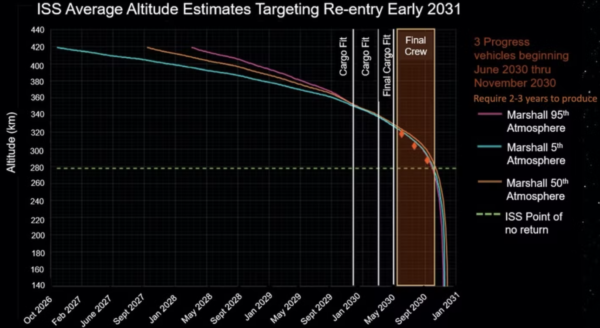

In January, NASA released an updated ISS Transition Plan to extend the station’s life through 2030. After that, the agency plans to decommission it by burning it up in the atmosphere and dropping whatever’s left in an uninhabited region of the South Pacific.

The ISS, originally planned to deorbit after 15 years, is old enough to legally drink a beer in the US. It’s still operational almost 22 years after the first long-term residents arrived. The station has been home to 258 astronauts from 20 countries and 3,000+ microgravity experiments. At ~$150B, it is often cited as the most expensive structure ever built.

Apart from its core scientific research and technology demonstrations, the station has been a testbed for a host of commercial cargo and crew spacecraft, including private astronaut missions. Half of the American segment’s research time has been dedicated to the ISS National Lab, which was instrumental in opening up the facility for commercial use.

The deorbit

Until earlier this year, NASA planned to cease operations in 2028, but the station was given a new lease on life with the 2030 extension.

The limitations in the station’s technical lifetime come from its primary structure, consisting of modules, radiators, and truss structures. Orbital thermal cycling and each docking and undocking add to the wear and tear. More station damage means higher risk to the crew.

NASA considered a range of decommissioning methods before landing on its current plan:

- Disassembly and return to Earth

- Boost to higher orbit

- Natural orbital decay with random re-entry

- Controlled targeted re-entry to a remote ocean area

The chosen approach: NASA chose natural orbital decay combined with a final reentry maneuver to limit the debris footprint. This method will consume a large percentage of propellant reserves. We have precedent for how the structure will behave: the Soviets’ Mir station and America’s Skylab.

The ISS’s fiery death will likely occur in three phases:

- Solar array and radiator separation

- Breakup of intact modules and the truss segment

- Individual module fragmentation and loss of truss structural integrity

After that, the external skin of the modules will melt away, heating and disintegrating the internal hardware.

Most hardware will likely burn up during the intense heating caused by reentry through the atmosphere, but there are some hardier components, like truss sections, that are expected to survive and land in the ocean.

The landing spot: Point Nemo, located 2,688 km from the nearest shore in the South Pacific Oceanic Uninhabited Area, is the farthest point from land on Earth. ISS partners chose this location because of its distance from populated areas in case any hardware survives the re-entry.

Commercial phaseout

Before the station fully deorbits in 2031, it will go through a transition phase to ensure continuity in crucial scientific research as a new commercial LEO ecosystem emerges.

NASA ultimately hopes to be “one of many customers in a robust commercial marketplace in low Earth orbit where cargo and crew transportation, as well as the destinations are available as services to the agency.” After the LEO handoff to the private sector, NASA will “buy” station time as a service rather than operate its own outpost. The agency will focus on deep space missions (to the Moon, Mars, and beyond)…and focus on Gateway, a station in lunar orbit.

Most recent RFI: The agency is seeking help from commercial companies to develop a spacecraft for the final re-entry maneuvers.

- NASA issued a Request for Information (RFI) on Aug. 19 requesting proposals for plans to develop a deorbit module that meets the requirements outlined in the Transition Plan.

- Responses are due Sept. 9.

- On par with its commercial plans, this request also solicits companies to highlight the “extensibility of such a module to serve commercial space stations.”

A new generation of stations

NASA is working with commercial companies to prevent any gaps in LEO access.

In late 2021, the agency announced $415.6M in Commercial LEO Destinations (LEO) funding for three companies: Blue Origin, Nanoracks, and Northrop Grumman. Each is leading teams that are developing space station concepts. This is the first phase of a two-part process.

- Until 2025, during the first phase, the chose ones will work with NASA to formulate and design LEO structures.

- After ’25, NASA plans to certify designs that can be operational by 2030.

As part of the LEO handoff, the structures will be fully owned and operated by the commercial space companies.

Blue and Sierra

Orbital Reef is billed as a “mixed-use business park” for research, industry, and tourism. It has a modular design so it can expand to accommodate larger crews. Amazon Supply Chain, Amazon Web Services, Arizona State University, Boeing, Genesis Engineering Solutions and Redwire Space are also working on the project. NASA awarded the team $130M through CLD.

Earlier this week, the companies announced that Orbital Reef passed its system definition review for NASA and is now ready to enter the design phase. For more, check out Pathfinder #0007 with Sierra Space CEO Tom Vice (Spotify, Apple, YouTube).

Northrop Grumman ($NOC)

NASA gave Northrop andDynetics, its partner, $125.6M to work on a concept leveraging its existing Cygnus module. Northrop will also adapt the Cygnus for the Habitation and Logistics Outpost on the lunar gateway space station, and is already in use as an ISS commercial cargo vehicle. Northrop’s station will initially host a crew of four, eventually expanding to eight.

Nanoracks and Lockheed Martin ($LMT)

Nanoracks, along with parent company Voyager Space and Lockheed Martin, received $160M for Starlab. The four-person space station design requires only a single launch, currently planned for 2027. The orbital outpost will have a docking node with an inflatable module on one side and a spacecraft bus, providing power and propulsion, on the other.

“There are lots of things we’ve learned along the way that will help us with Starlab and building up that station,” Nanoracks’ Cooper Read recently told Payload, referring to the company’s flight-proven hardware on the ISS.

Axiom (with an assist from SpaceX)

Beyond CLD, NASA awarded Axiom $140M in 2020 to develop a habitable attachment to the ISS as part of the agency’s broader Next Space Technologies for Exploration Partnerships (NextSTEP). Axiom is developing its own space station, Axiom Hab One, which it hopes to launch in 2024. The company has also already operated the first commercial crewed mission to the ISS, Ax-1. For more, check out Pathfinder #0001 with Axiom CEO Mike Suffredini (Spotify, Apple, YouTube).

Timeline concerns

Both NASA’s Office of Inspector General (OIG) and the Aerospace Safety Advisory Panel have questioned the realities of proposed timelines for replacing the ISS with commercial alternatives.

Auditors from each organization have warned that timelines were unrealistic and that it’s unlikely a commercial station will be ready until the 2030s. Both NASA and the four companies working on the stations expressed that they do not share these worries and reiterated confidence in their initially proposed timelines.

Russia & China

Yuri Borisov, Roscosmos’s new chief, caused quite the stir in July by announcing that Russia would cease ISS operations after 2024. This threat spurred NASA to question its remaining dependencies on Russian technology, such as the station’s propulsion and control systems.

- Both Northrop’s Cygnus and SpaceX’s Cargo Dragon module may be viable alternatives.

Luckily, this threat didn’t last long. NASA and Roscosmos sat down to confirm continuation of joint ISS operations after 2024. And Russian-American seat swaps are proceeding as planned. However, it’s an open question as to whether Russia will begin working on its own LEO station by 2024.

China is already building its own space station at breakneck speed. In July, the China Manned Space Agency launched the latest part of its in-progress Tiangong station. The Wentian laboratory is the single heaviest spacecraft module ever sent to orbit. The final module, Mengtian, is slated for launch in October of this year.

The upshot

The next few years will be a highly crucial crunch time for NASA and commercial space station developers.

As we wrote in December, there are high stakes here: “If the ISS goes offline before American astronauts and spacecraft have somewhere else to go,” OIG warns that:

- NASA would lose a gateway for deep space exploration.

- Scientific and technological missions would lose an on-orbit hub.

- Crewed trips to the moon and Mars would inevitably be delayed.

- A fledgling LEO commercial space economy ‘would likely collapse.’”