(Editor’s note: This is Payload Research analysis and is also not investment advice.)

Space businesses have gained a reputation as cash-burning machines. Investors typically fork over tens of millions in development dollars before a startup can launch a single piece of hardware. Even when the tech eventually reaches orbit, it often fails due to space is hardtm, necessitating further development and rescuing funding.

Rocket startup ABL Space Systems showed just how excruciating that deep R&D phase can be this week when a static fire test destroyed the company’s second RS1 rocket, dashing hopes of reaching an orbital proof point anytime soon. The company has raised $460M+.

However, for those who can endure the gut-churning upfront costs of building for space, the end product *can* be orbiting hardware with great unit economics, significant cash flow, and an elongated barrier to entry timeline.

Iridium provides a good example of the sector’s R&D lifecycle.

Iridium provides global satcom connectivity via its LEO constellation. The core services include voice, data, IoT, and government connectivity, which the company insists are generally companion/supplementary/backup services rather than broadband, allowing it to coexist with Starlink and an AST SpaceMobile.

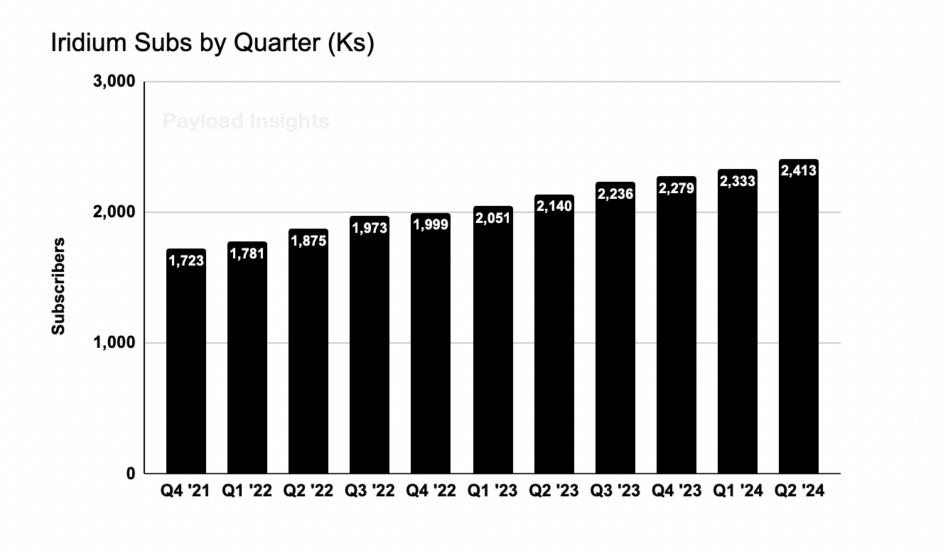

Iridium released its Q2 earnings report yesterday, announcing that its subscription base grew 13% YoY to 2.4M, revenues were up 4%, and, most importantly, the company continued its rapid pace of returning significant capital to shareholders via dividends and substantial share repurchases.

The stock jumped 7% on the news, despite being down over 30% YTD.

The company completed its 66-bird NEXT constellation in 2019, reaching positive cash flow that same year and commencing its share repurchasing two years later in 2021. Since the buyback program started, the company has repurchased $819M of its shares. Iridium reiterated that it’s on track to return an additional $3B of capital by 2030 (its market cap is $3.4B today).

To understand Iridium and the satcom business model, let’s look at its R&D lifecycle.

The chart, which looks like it may have originated from a high school econ textbook, depicts the R&D lifecycle of automobiles. It’s an oversimplified view, which I like because it allows the peaks and troughs to be generally applicable to any tech development.

The R&D tech cycle:

- High upfront development costs (trough)

- Revenue generation and positive cash flow recouping initial investment (up slope)

- Over time, competition is introduced putting pressure on margins (down slope)

- R&D investment begins again (trough)

The Iridium R&D cycle:

- The company invested $3B in its 66-bird NEXT constellation

- Iridium now generates meaningful cash flow from the constellation as it recoups its investment and returns capital to shareholders (we are here)

- Competitors eventually put pressure on margins as the fleet ages and innovation enters the market

- Management decides whether to start the R&D cycle again with its NEXT constellation decommissioning around 2035

Iridium spent ten years and $3B on the design, construction, and launch of its 66-satellite NEXT constellation, putting the back-of-the-napkin cost per satellite at ~$45M. The company completed the constellation in 2019, just as SpaceX began to deploy its first Starlink satellites.

While Starlink’s rapid rise has certainly slowed Iridium’s growth, the disruption has been manageable as the two companies compete in different core markets (broadband vs. complementary/backup connectivity).

The same can not be said for fellow satcom provider Hughesnet, whose target market sits directly in the path of SpaceX’s home broadband storm.

Iridium’s growing subscriber base has helped propel company revenues to over $200M a quarter. Since the company’s 66 satellites will require minimal further investment over its 17 year lifespan, a significant portion of that revenue can fall all the way down to the bottom line, which is the appeal of satellite services.

Business model: The company sums up its business model as: Leverage our largely fixed-cost infrastructure to grow our service revenue.

“Our business model is characterized by high capital costs, primarily incurred every 10 to 15 years, in connection with designing, building and launching new generations of our satellite constellation, and a low incremental cost of providing service to additional end users,” the company wrote in its 2023 10-K.

After achieving positive free cash flow in 2019, the company opted to start returning cash directly to shareholders rather than embark on expensive side quests. It’s a rare old-school approach that has largely gone out of fashion for tech companies over the last two decades, with VC and PE shops prioritizing top-line growth over cash flow.

In Q2, Iridium spent nearly $100M repurchasing shares, even financing a portion of the buybacks with debt. The company also announced it will raise its dividend, which is currently north of 2%.

By 2030, the company’s $3B NEXT constellation development costs should be more than paid back. With the company re-forecasting its satellite’s lifespan from 12.5 to 17.5 years, Iridium could continue returning free cash flow to shareholders via the constellation until 2035-37.

Going back to the R&D life cycle chart, what will happen when Iridium’s satellites begin to age, and the company returns to the heavy R&D stage of the cycle?

Almost every company elects to start the investment cycle back up again.

Often there is a legitimate angle to out-innovate a competitor. But sometimes there’s not, and it’s management hubris that encourages the company to forge ahead. Regardless of the rationale, you rarely see management opt out of the next cycle and just run the business for cash.

Iridium still has 5 to 10 years to decide whether to go through another multi-billion dollar constellation development cycle, but the decision is far from obvious. On the one hand, Iridium has the expertise and distribution networks to continue competing in one of the world’s largest markets: connectivity. On the other hand, competing against mega-players like Starlink and Kuiper as a companion service is a daunting road ahead.

Starlink and Kuiper

Starlink announced last year it reached breakeven cash flow. The company will likely improve cash generation this year, as we expect Starlink revenue to come in around $7B. The company can build and launch its V2 mini satellites for less than $2M per bird.

SpaceX has repeatedly said cash flow from the satellite internet network will fund its Mars colonization goals (fun fact, Starlink’s logo is the Mars transfer orbit).

Amazon is investing $10B in its 3,236-bird Kuiper constellation, bringing the back-of-the-napkin price per satellite to ~$3M. The constellation deployment has been delayed due to holdups with Vulcan, Ariane 6, and New Glenn.

Both Starlink and Kuiper have shorter lifespans than Iridium’s NEXT satellites, which will require the two giants to continuously spend on replacement satellites yearly to maintain the high-churn constellation.