The space industry is built on a one-way street.

Decades of innovation have made humanity very good at getting spacecraft and satellites into orbit, but companies are still working on an efficient return lane for cargo, which will enable the long-promised in-space manufacturing industry.

One startup leading that charge is Outpost, which is taking a fundamentally different approach to getting things home from orbit. The LA-based Earth return company is preparing for the first launch—and return—of Carryall, a spacecraft the size of a shipping container, the company revealed to Payload.

The current method: Since the early days of human spaceflight, Earth return technology has remained largely unchanged. Space capsules returning from orbit are fitted with ablative heat shields to withstand the immense heat of reentry. They’re filled with large stores of propellant to forcibly decelerate through the atmosphere, and have heavy parachutes or parafoils, which deploy at low altitudes to bring the capsules the rest of the way home.

As a result, space capsules have limited capacity and a hard time hitting a predetermined target on the ground. Anyone trying to get things—from science experiments to pharmaceuticals manufactured in orbit—back to Earth faces extremely high costs, which ultimately limit the number of things that can be built or tested in space and brought back intact.

“The companies that have been successful at this, fundraising at least, they’ve found use cases of things that can fit into these small capsules that have immense value. So, something that can fit into a test tube or a vial that’s worth millions of dollars,” Outpost CEO Jason Dunn told Payload.

However, the future of manufacturing in space depends on Earth return companies finding a way to return much larger volumes from space—like say, shipping containers.

The Outpost system: Outpost’s Ferryall and Carryall spacecraft combine a number of relatively simple technologies to return objects from orbit in a revolutionary way. These components include:

- The satellite bus: This carries the propulsion system that allows the spacecraft to maneuver in orbit and send itself back to Earth.

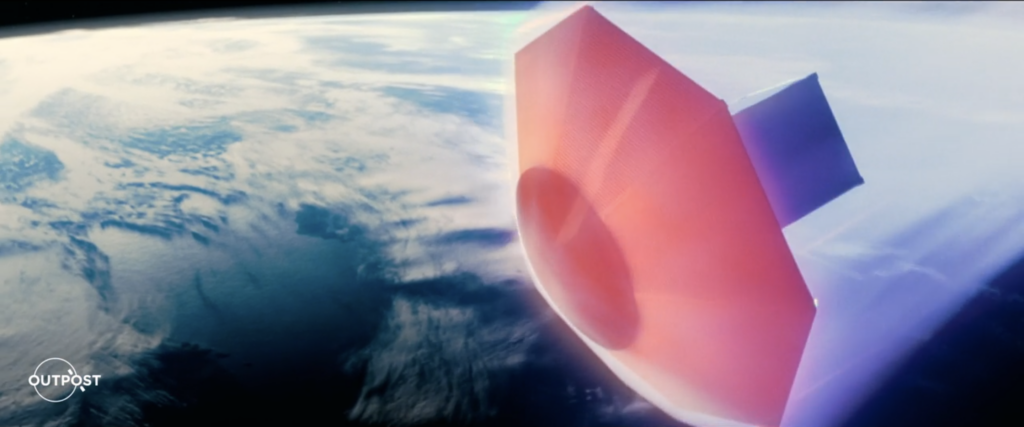

- The heat shield: Outpost’s heat shield, which uses technology developed by NASA and was flight tested in 2023, is made of a 3D woven carbon fiber fabric that unfolds in orbit to protect the payload and slow the vehicle down.

- A container: Ferryall can carry a payload of 100 kg, while Carryall is the size of a standard 20-ft shipping container and can host payloads up to 10 tons.

- A robotic paraglider: Upon reentry, a paraglider wing deploys and robotically guides the spacecraft to its destination with pinpoint accuracy.

Ferryall, the smaller model, is designed for SpaceX’s rideshare architecture, while Carryall will be able fit into current mid-sized launchers, such as the Falcon 9.

How it works: Once in orbit, Carryall exits the launch vehicle and unfolds its heat shield.

- The spacecraft’s onboard propulsion system allows it to maneuver as any other satellite does. When it’s ready to come home, it orients itself toward a reentry trajectory and begins its descent.

- From here, the heat shield shows off its unique benefits. Through radiative cooling, it protects the payload behind it from excessive heat without the need for a back shell. More importantly the heat shield’s large surface area slows the vehicle down to subsonic speeds much faster than capsules or lifting body space planes can.

- At about 30 km, Carryall deploys a drogue parachute, which stabilizes the spacecraft and further reduces its speed while the heat shield closes.

- At around 20 km, Carryall releases its parachute and opens its robotically controlled paraglider wing, which allows Outpost to provide point-to-point delivery, anywhere in the world, with incredible accuracy.

“Earth return is not about just returning to Earth. It’s about returning to a very specific place on Earth. We want landing pad precision,” Dunn said.

Over the course of more than a hundred flight tests, the company has honed this accuracy. In one, the test craft deployed its paraglider wing from a weather balloon at an altitude of 20 km, and it flew over 180 km downrange, landing on a 5m target.

Future payloads: Taken together, this system allows companies to test things in space with the intent of returning them home, and to manufacture massive quantities of goods for sale back on Earth.

“Because our entire entry system is fabric and lightweight and low mass, we can dedicate a huge amount of our vehicle to the customer’s payload. A typical capsule returning from space has a 5%, maybe 10%, payload mass fraction. We’re in the 50% and higher range,” Dunn said at the Amazon MARS conference in 2023.

Outpost intends to drive down the cost of manufacturing in space and open the door for new manufacturing use cases that would be cost-prohibitive with other reentry systems. Additionally, the company hopes its technology will decrease the amount of space junk in orbit and boost reusability.

- The company has already signed a $1.7M deal with the DoD to build a ferry spacecraft to support ISAM missions.

- It’s also partnered with NASA to develop the Cargo Ferry, which will be used to return things from commercial space stations and the ISS, a company spokesperson told Payload.

What’s next: The first Ferryall mission is planned for early 2026, with early customers likely coming from the US military for point-to-point delivery and commercial companies looking to run quick, iterative tests in orbit. Carryall could fly as early as 2027.