Ed. note: This is Payload Research analysis. You can sign up for our Research newsletter here.

The next few years are make or break for launch startups—either achieve orbit and scale or go the way of Astra and Virgin Orbit.

Over the next two weeks, Payload will examine the capital raised by launch startups, how dollars are being spent, the product roadmap progress, and how (or if) the companies fit into the future of launch.

There are two key categories of launch in our mind: economic launch and responsive launch. SpaceX has achieved dominance in economic launch (in other words, it’s unlikely that any launch company will match their economics anytime soon). However, the responsive category (launching at any time into any orbital plane at a reasonable cost) is still up for grabs and is a market that can create a few sustainable winners.

Team yet to orbit: Today, we will cover the launch startups that have yet to reach orbit: Relativity, ABL, and Stoke.

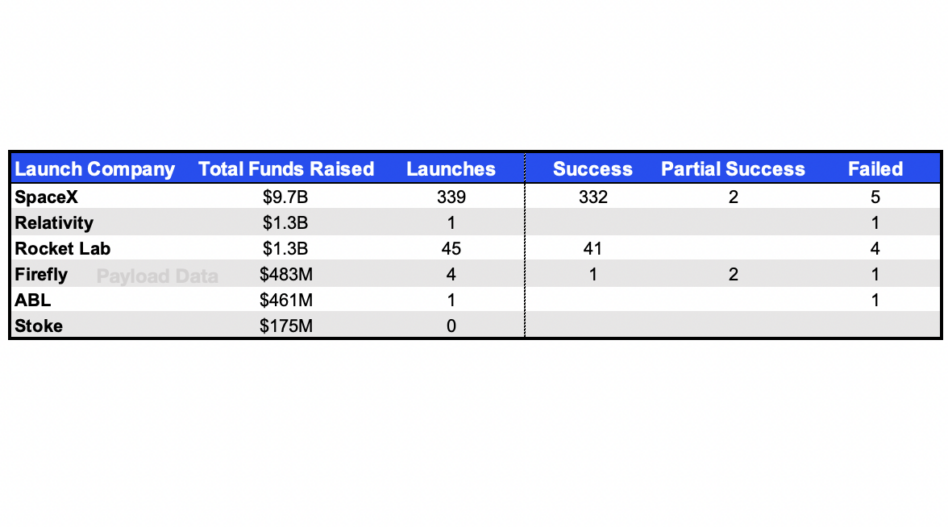

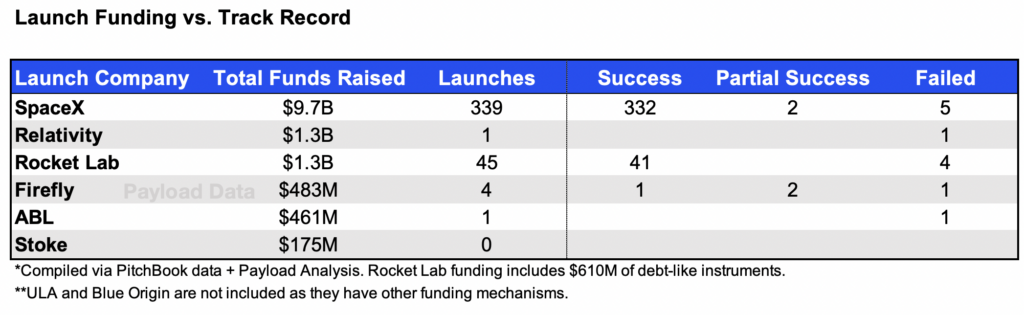

Relativity and ABL have each launched once, with both attempts failing to reach orbit.

History says that’s OK: 47% of maiden launches suffer a significant anomaly, according to ESA chief Josef Aschbacher. SpaceX’s first rocket, the Falcon 1, failed to reach orbit on its first three launches. New rockets needing multiple shots on goal is almost expected in the rocket game.

However, the launch investing landscape is maturing, and investors now have a shorter leash, careful not to throw good money after bad.

Relativity Space

Relativity has raised $1.3B since its inception nearly a decade ago.

Its most recent round, a 2021 $650M Series E, saw participation from Blackrock, Coatue, Baillie Gifford, Caruso Ventures, Fidelity, Mark Cuban, Tiger Global, and 25 other investors, according to Pitchbook data.

Thank you, next: The first rocket Relativity developed was the Terran 1, designed to transport 1,250 kg to LEO. Terran 1’s 2023 maiden launch ended in failure when the vehicle experienced a second-stage engine anomaly.

Terran R: Following that launch, Relativity determined that expendable small launch vehicles were not economically viable over the long run, and decided to shut down its Terran 1 program to go all in on the heavy-lift and reusable Terran R.

- Terran R is designed to transport 23,500 kg to LEO with first-stage reusability or 33,500 kg to LEO in an expendable configuration.

- The company says the rocket will debut in 2026.

Small→ large rationale: When asked in a recent Payload interview if investors have pushed back due to the lack of an orbital proof point, Relativity CEO Tim Ellis said, “Getting to orbit would have been a huge proof point and would have helped us…but weigh that against going to orbit with the wrong product. Terran 1 is interesting but not that interesting. Terran R is very interesting from a product-market fit, and the total addressable market is 20x larger. We are building the next alternative to Falcon 9.”

Our take: Relativity had a second Terran 1 far along in production in preparation for flight two. So, why not try to hit such a critical technical milestone? Management’s explanation is that the first launch was enough of a success that it did not warrant a second test. We believe that a better explanation might be found in the funding environment.

When raising funds so close to a potential launch milestone, investor decisions often hinge on the result. We believe the more reasonable explanation here is that Relativity decided not to take the risk of a second launch to avoid a negative proof point and instead refocus investor attention on a larger SpaceX-like launch vehicle (which also arguably helps justify a $4B+ valuation).

Incoming Series F?: Sources tell Payload the company has gone out to market to raise a $1B+ Series F round, which, if closed, would bring Relativity’s total funds raised to a staggering $2.3B. To put that in perspective, Rocket Lab’s market cap sits at $1.75B, and Blue Origin is eyeing an acquisition of ULA for roughly $2B-$3B.

Falcon 9 vs. Terran R: At 23,500 kg to LEO in a reusable configuration, the Terran R looks a lot like Falcon 9.

- SpaceX spent ~$400M to get to a non-reusable Falcon 9. If we factor in over a decade of inflation and the millions more spent to get to reusability, we can reasonably ballpark estimate Falcon 9’s full R&D costs to be in the billion-dollar range.

Terran R costs: Ellis similarly characterized the cost of developing Terran R at roughly one billion dollars.

We think that R&D number may be true if you just take the capital needed from here on out, but if we factor in the $1.3B of capital raised for development costs thus far plus another billion dollars the company is seeking in the Series F, the net spend to get to Terran R could reach $2B+.The biggest question in our mind is who’s willing to fund the business now that an orbital proof point has pushed itself out a few more years?

However, if investors can stomach the high upfront cost and the inevitable stumbles of a new rocket, particularly one attempting reusability out the gate—there could be a big reward at the end of the launch plume in the form of a reusable rocket more capable than Falcon 9. That’s assuming there’s meaningful market share left to grab, with New Glenn, Vulcan, Starship, Neutron, and Ariane 6 all set to add capacity in the next year and change. It is a high-risk, high-reward bet that Relativity argues is the right approach to compete in the next era of launch.

ABL Space Systems

ABL Space Systems was founded in 2017 and has raised $461M of capital. The bulk of the funding came from a 2021 $372M Series B round led by T. Rowe Price and included participation from Fidelity, In-Q-Tel, and Lockheed.

ABL also won a $60M Space Force STRATFI award last year that included $30M of government funding and $30M of match funding from private investors. The award represented a creative opportunity to raise non-dilutive government funding and encourage private investors to participate.

RS1: ABL is developing the expendable RS1 rocket, which is capable of transporting 1,350 kg to LEO. The rocket is propelled by nine gas generator E2 engines—which the company calls “intentionally boring” for simplicity and reliability.

Maiden launch: The RS1’s maiden launch in January 2023 ended in failure shortly after liftoff due to a power anomaly. ABL is conducting pre-launch operations ahead of flight two.

Launch in a box: At 1,350 kg, ABL’s RS1 rocket is solidly positioned within the small launch market. Its differentiating feature is its GS0 “launch in a box” system, which allows the company to launch from virtually any flat surface in the world.

- The GS0 pad and rocket can be packaged in shipping containers for transportation.

- ABL believes the launch site flexibility offers a strategic advantage in responsive launch, particularly for the government, which prioritizes resilient launch.

“Over the past five or six years, there was an initial wave of investment into launch purely based on the success of SpaceX and the incredible gains that early investors were able to achieve on the investment,” Dan Piemont, ABL’s cofounder, told Payload in a recent interview. “There was a lack of understanding of the risks that make it difficult to be a successful launch business. Now there is a much better understanding.”

Piemont believes there are three key characteristics that launch investors are looking for:

- Technical capability: The engineering needs to be technically sound.

- Is there demand? Just because you have a capability doesn’t mean it’s valuable.

- Economics: Does the architecture have solid unit economics?

ABL’s breakeven point: The company falls into the small and responsive launch category, providing a custom launch service for a premium. The expendable small launch market is notoriously difficult to reach profitability given the need for a high launch cadence to cover fixed costs. The company says it’s hyper-focused on a sustainable launch model, telling Payload it expects to be able to break even at a single-digit yearly launch cadence.

However, the company still has a lot to prove (and more cash to spend) to get to that single-digit cadence, as it is still searching for its first orbital proof point.

+ Stoke Space

Stoke has raised $175M. It is still early in its development cycle and a year or two away from its first orbital launch attempt, but the startup is worth mentioning due to the investor interest it is receiving. Investor enthusiasm is driven by the company’s pursuit of a milestone that even Falcon 9 couldn’t hit: a fully reusable rocket. We believe Stoke could be the last new US launch startup to receive significant funding for quite some time.

Stoke’s full reusability:

- The rocket’s novel second stage resembles a reentry capsule with a large circular heat shield.

- However, instead of large engines poking out of the bottom, it employs 30 small thruster openings arranged around the perimeter of the heat shield.

The company hopes this will solve the second-stage expendability problem and lead to dramatically improved economics.

Elephant in the Room: Virgin Orbit and Astra

Last year, the launch market saw two startups—Virgin Orbit and Astra—leave their investors in the dust. We believe the investments were more of a warning against betting on fundamentally unsustainable business models, rather than a referendum on the small launch category. Let’s discuss.

The Virgin Orbit story: Like ABL, Virgin Orbit also emphasized its resilient launch approach, featuring the ability for its first stage (a modified Boeing 747) to take off and land on a runway. The company experienced four successful launches and two failures. However, its cost structure was the real issue and never gave it a fighting chance. Virgin Orbit’s development costs were in the billion dollar range, it carried ~$150M in annual staffing cost, and shouldered hefty Boeing 747 maintenance costs. With a per launch price tag of just ~$12M, revenue could never be able to keep up with costs. The economics were flawed.

The Astra story: Astra’s costs were significantly lower, with a reasonable headcount and moderate R&D expenses. However, the company’s rocket was tiny and carried an equally small launch price tag of roughly $3M-$5M. Like Virgin Orbit, Astra would have had to launch an awful lot of rockets to cover its fixed costs.

End food for thought: SpaceX has launched over 300 times, with reusability driving healthy gross margins, and yet it has only recently begun squeaking out a profit.